The neighborhood now known as Uptown has gone by different names over the years. Bordered by the Dallas North Tollway to the west, Woodall Rodgers Freeway to the south, and Central Expressway to the east, Uptown was once defined by the streets that cross its interior: Maple, Oak Lawn, Cedar Springs, and Fairmount. The area came into its own in the late 1950s and 1960s, when it was likened to New York’s Greenwich Village. A group of up-and-coming artists— assemblagists David McManaway and Roy Fridge, sculptor Herb Rogalla, and painters Roger Winter and Bill Komodore—moved into the affordable bungalows that lined the streets of Oak Lawn and became loosely identified as the Oak Lawn Gang. These artists created a close-knit community, hosting “moonshine” parties where it was not unusual for guests to come in costume and dance to music by Fridge on tub bass and Winter on guitar. Winter recalls those gatherings:

One spring night in 1963, David [McManaway] called me from the Standup Bar and asked me to bring my guitar there. He said that a large group from the DMCA membership and staff had dropped by for a beer and that Roy [Fridge] had his tub bass and he had his banjo. When I got there, the group had literally taken over the place. I got into the mood of it, and we played for several hours. A drunk redneck at the bar danced by himself right through to the end. When we left, this guy shook my hand and said I “had it.” I consider this the best and purest compliment I have ever received.

Inexpensive housing was not the only appeal. The city’s earliest galleries and art spaces also opened in the neighborhood and employed many of the artists who lived nearby. Atelier Chapman Kelley, C. Troup Gallery, Nye Galleries, and Cushing Galleries were all established by the 1960s, and Uptown gained its first art museum when the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts (DMCA) moved to Turtle Creek in 1959.

A Vibrant but Short-Lived Contemporary Art Museum

The Dallas Society for Contemporary Arts (DSCA) was established in 1956 by a group of artists, architects, theater directors, photographers, and critics led by the sculptor Heri Bert Bartscht. The DSCA organized exhibitions at the Courtyard Theater off Maple Avenue in Uptown until it opened a permanent location at the Preston Shopping Center in North Dallas in November 1957, officially becoming the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts. In its new space, the museum held several important exhibitions organized by board members. The inaugural exhibition, Abstract by Choice, featured work by Stuart Davis, Max Weber, Marsden Hartley, and Piet Mondrian on loan from major New York galleries and museums, including the Downtown Gallery, the Sidney Janis Gallery, and the Museum of Modern Art. Other notable exhibitions included Action Painting, with work by Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, Richard Diebenkorn, Jackson Pollock, and Franz Kline, and Laughter in Art, organized by board member Betty Blake, featuring Joseph Cornell, Dallas artist Roy Fridge, Jasper Johns, Houston artist Jim Love, Robert Rauschenberg, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Recognizing the need for a more cohesive and ambitious exhibition program and an advisor on acquisitions, the DMCA board began the search for a director while also looking for a new home for the expanding museum. By late 1959, art historian and museum administrator Douglas MacAgy was named director, and the museum moved to the former Slick Airways building at 3415 Cedar Springs Road in Uptown. MacAgy oversaw a rigorous exhibition schedule, which included important shows like Signposts of Twentieth Century Art, curated by art historian, critic, and art dealer Katharine Kuh of Chicago; Contemporary Japanese Painting and Sculpture; the first retrospective exhibition in North America of René Magritte, in collaboration with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Art of Assemblage; and 1961.

The exhibition 1961 generated controversy in the Dallas–Fort Worth art communities over two commissioned works by the contemporary sculptor Claes Oldenburg. For Store, which seemed to be the more traditional of the two, the artist transported his New York installation of mundane objects made of plaster to a gallery at the DMCA and reinstalled them to resemble a storefront (Fig. 1). The work is now considered a prime example of pop art, which elevates the everyday to the status of art object. But local reactions at the time ranged from minor discomfort to a full-blown visceral reaction by Fort Worth artist Bror Utter, who took a bite out of a plaster slice of pie at the opening. Roger Winter describes the incident:

Claes had a slice of like a meringue pie. I think something like a lemon pie, coconut pie made of plaster and enamel and probably burlap and chicken wire as the structure of it, and it was sitting on a little saucer on a chair that he’d borrowed from David and Norma McManaway, a blue chair—just an old-timey kitchen chair—and a painter from Fort Worth, . . . Bror Utter, came with a friend of his, Sam Cantey, who was, I think, president of one of the better banks in Fort Worth. And Bror, I think, got a little drunk and he was so outraged by all of this [Oldenburg’s installation] that he picked the piece of pie up off the chair and bit a piece out of it. . . . That seems always to me to be a remarkable reaction to art.

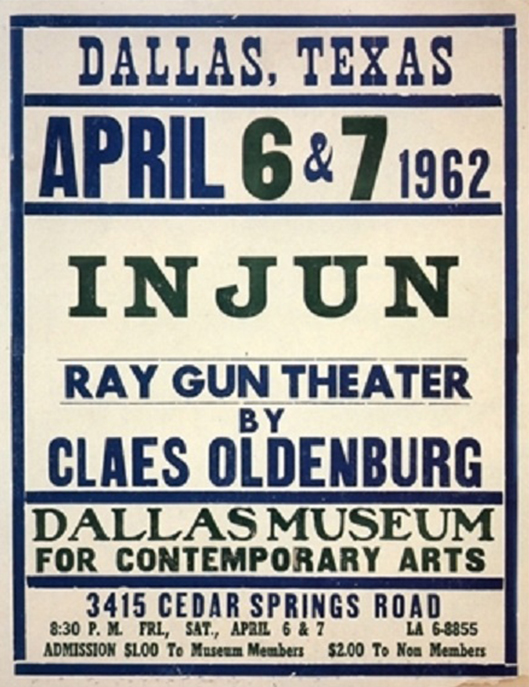

Oldenburg’s other commissioned work for 1961 was perhaps the most infamous event at the DMCA: the first of the artist’s “happenings” outside of New York City and the first commissioned by a museum. Titled Injun, it was performed on the DMCA grounds on two evenings (Fig. 2). With his wife Pat, DMCA staff, and painting students from the University of Texas at Arlington, the artist took over an abandoned house and guided visitors through various room installations to the sounds of Native American drums and chants. In the climax of the performance, Oldenburg dragged his wife’s limp body onto the roof of a shed behind the house and chopped a tornado-like object made of papier-mâché. Winter has these memories of the happening:

Joe Hobbs is the painter who taught at Arlington State [now the University of Texas at Arlington] at that time. . . . And he and a group of his painting students all were wrestling around on the floor. Hal Pauley was in the room with some newspapers playing, or pretending to play, a violin. There were just rooms in this house, and Claes was dressed up like an Indian in . . . some kind of savage-looking costume made out of shredded papers. He was dancing and moving around. . . . To view it we held on to a rope and sort of moved in through the rooms in the building that belong to the DMCA, moved in a certain direction. And I heard someone say behind us, “Boy, the membership in the DMFA is going to skyrocket tomorrow! . . .” Because it was so different for Dallas at that time.

MacAgy earned great respect and admiration from local artists—some of whom worked on the museum staff—because he included them in major exhibitions alongside artists with national recognition. David McManaway and Jim Love were part of the Dallas showing of the traveling exhibition The Art of Assemblage, while Roy Fridge designed exhibition catalogues for 1961 and The Art that Broke the Looking Glass and exhibited his own work in 1961. Many artists were disappointed when the DMCA merged with the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1963, fearful that the loss of their powerful and loyal ally in the highest ranks of the museum community would mean a return to the less-visible status quo, with fewer opportunities to show their work. Winter recalls his fondness for MacAgy and the environment surrounding the DMCA:

Douglas was the nucleus, the star, the center. . . . And I think he generated quite a bit of it [energy], but then we were some interesting characters there and this was the time when we lived in what I’d call an “exotic poverty.” None of us had any particular money, but we worked and we were very excited about our work and there was a lot of interchange. I especially was influenced by . . . David McManaway, but also Roy Fridge. Jim Love lived in Houston, but he flew up to, ironically, Love Field, to Dallas.

In addition to major exhibitions and acquisitions—like Henry Matisse’s Ivy in Flower, 1953 (Fig. 3), Paul Gauguin’s Under the Pandanus (I Raro te Oviri), 1891 (Fig. 4), and Francis Bacon’s Walking Figure, 1959–1960 (Fig. 5)—the DMCA offered community programs such as the Children’s House, directed by Paul Rogers Harris with Peggy Wilson (Fig. 6), and a weekly film series organized by board members Major and Downing Thomas. After the merger, Harris moved his children’s art program to the Little Red School House at KERA-TV Channel 13, the local public television station, where he continued to offer instruction in painting and graphic arts.

The DMCA’s move to Uptown stimulated the district’s already-burgeoning arts activity. Through his contacts at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, local artist and gallery owner Chapman Kelley brought in East Coast artists for exhibitions at his Atelier. Eventually, his roster included new-to-Dallas artists Jeanne and Arthur Koch and arts and technology whiz Alberto Collie, who dazzled Dallas audiences with his floating sculptures.

Mary Nye’s Nye Galleries focused heavily on artists who taught at East Texas State University, as well as emerging and established regional artists like Dallas sculptor Heri Bert Bartscht, Texas painter Cecil Casebier, and local painters DeForrest Judd and Otis Dozier (Fig. 7). Local painter Bill Komodore once commented that the Nye Galleries’ walls were covered in burlap and that Mary Nye herself “was like a New York dealer, in that she would never bother to look at your work (Fig. 8).” Despite this lighthearted criticism, Nye was seen as a serious gallerist, putting on exhibitions and representing artists for the next two decades.

A Gallery District Emerges

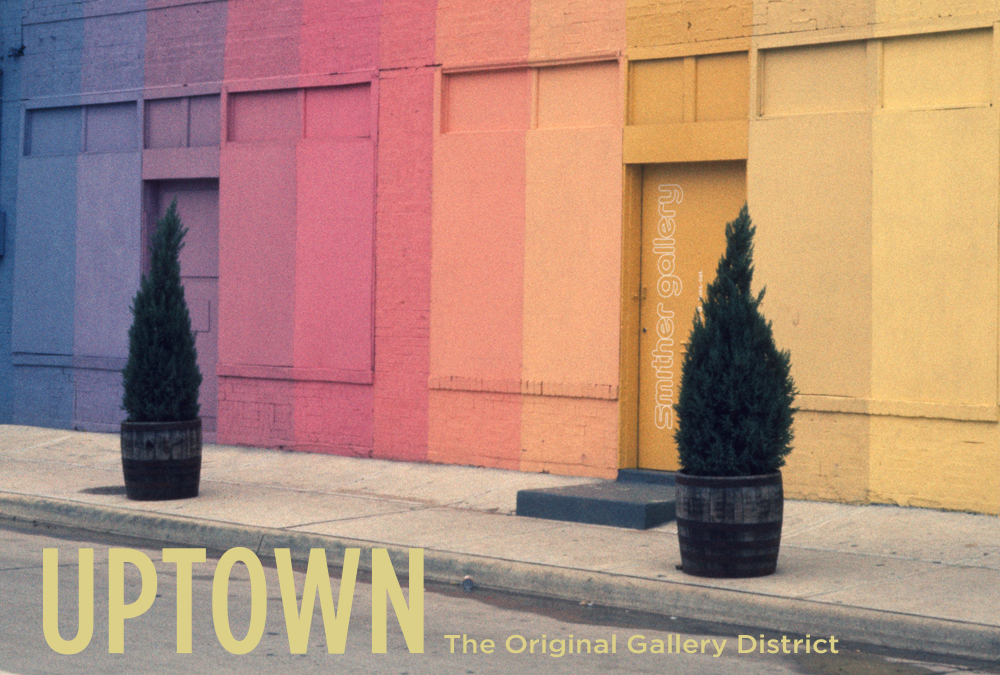

By the 1970s, the success of several galleries had turned Uptown into a true gallery district. While do-it-yourself spaces were the norm in other active parts of town, like South Dallas, the Uptown galleries had a more polished, commercial presence. Their approaches varied. Some, like Janie C. Lee Gallery, chose to bring the national art scene to Dallas. Others, including Smither Gallery, exhibited both national and local artists. Still others, like Delahunty Gallery, put Dallas artists on a national stage. The Uptown neighborhood was also home to Dallas’ first photography galleries: Afterimage, established in 1971 in the Quadrangle by Ben Breard, and the Allen Street Gallery, a do-it-yourself space opened in 1975 on Allen Street that developed into a recognized commercial gallery.

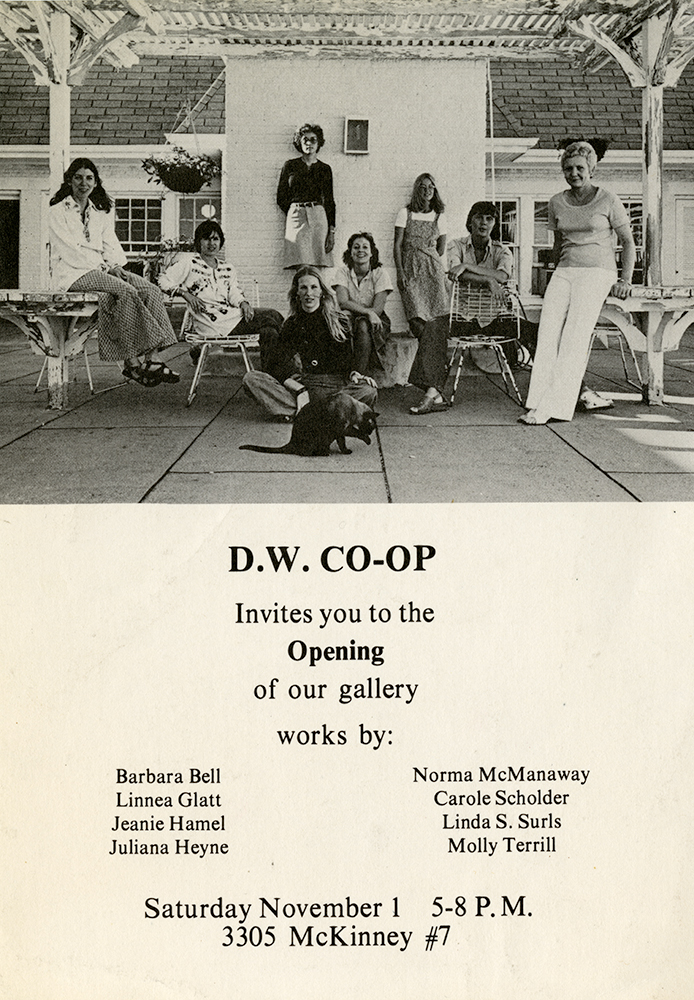

Like Allen Street Gallery, the Dallas Women’s Co-op started as a cooperative gallery space, with its members staffing the gallery and paying dues in exchange for exhibitions (Fig. 9). It was established in 1975, just two years after Judy Chicago and other women artists opened the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles at the height of the second-wave feminist movement. The women behind DW Co-op wanted a similar space where local women artists could control what work was exhibited and how. Over the decades, DW Co-op named a governing board, changed its name to DW Gallery, and began giving exhibitions to men and women. The first exhibition to include men featured the work of locals Sam Gummelt and David McManaway with Houston sculptor Jim Love. Notable exhibitions included Wearable Works (1978); Gift Wrap (1979), with works on the theme by former Dallasite Rick Maxwell, Gilda Pervin, Tom Orr, and other gallery artists; and Book Exhibit (1982), curated by gallery director Diana Block. Some of the emerging artists who showed there—including David Bates, Clyde Connell, Danny Williams, and Otis Jones—went on to enjoy national reputations. What started as a 500-square-foot gallery space above a restaurant in Uptown expanded in 1983 into a Deep Ellum warehouse with more than 20 nationally known Texas-based artists on the roster and 2,400 square feet of exhibition space.

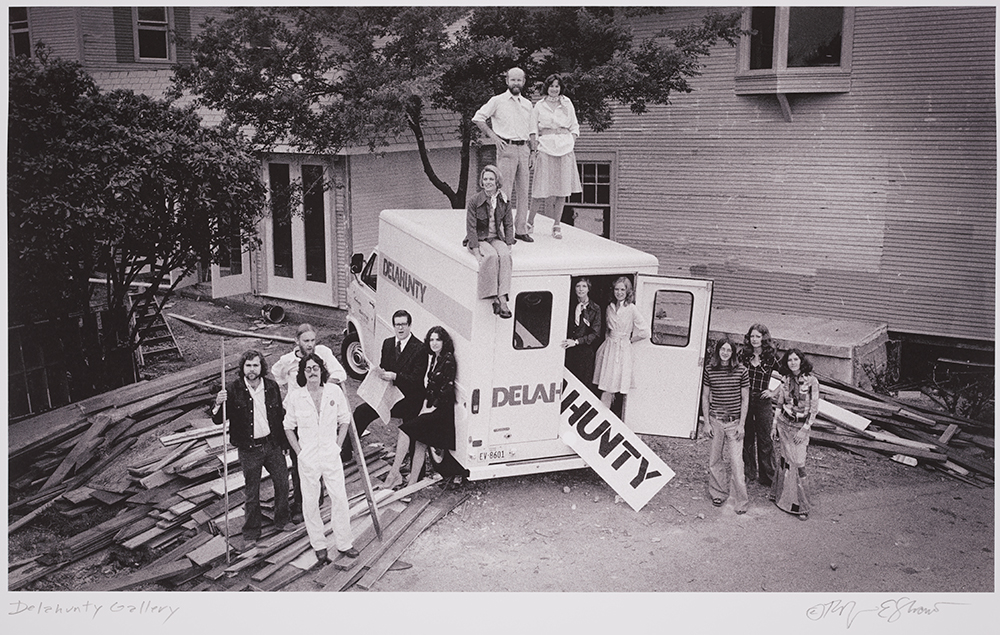

Two of the most successful galleries in the Uptown area were bookends for the 1970s: Janie C. Lee Gallery, established in 1967 (Fig. 10), and Delahunty Gallery, launched in 1974 by Laura Carpenter, Murray Smither, and Virginia Gable (Fig. 11). The two spaces fared differently in Dallas, owing in part to economics but also to timing. In some ways, the Janie C. Lee Gallery paved the way for a gallery like Delahunty, which enjoyed greater success even though it showed similar work.

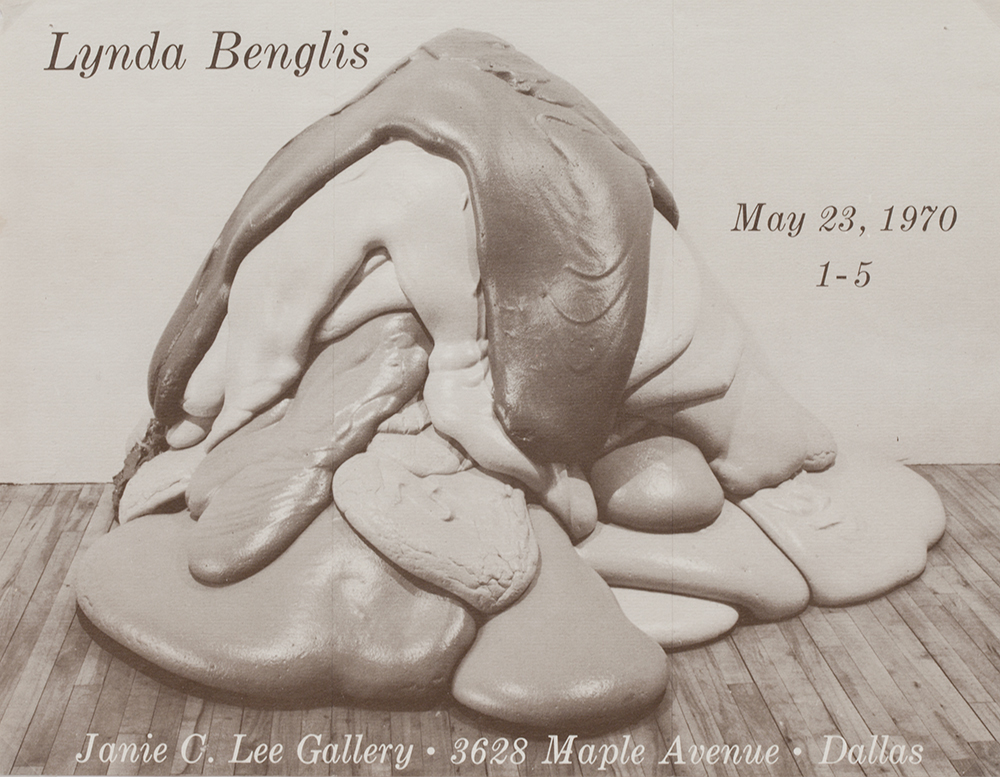

Janie C. Lee was ahead of her time for the artists and styles she introduced. She had spent several years in New York City, and she had the sophisticated taste and the right contacts to bring the national contemporary art scene to Dallas. Her relationship with New York gallery owner Leo Castelli was the source of much of her inventory, which she showed on consignment. In the early years, Lee ran the business from her apartment at 3525 Congress Avenue, but by 1970, the gallery had its own location at 3628 Maple Avenue. Highlights of exhibitions there included the 1969 exhibition of work by Frank Stella, Darby Bannard, David Diao, Robert Morris, Donald Judd, and Richard Serra; the 1970 exhibition Bengston/Price, by Californians Billy Al Bengston and Ken Price; the 1970 solo exhibition of work by Lynda Benglis (Fig. 12); and the 1972 exhibition New Paintings, Drawings, and Lithographs by Cy Twombly (Fig. 13). Lee’s minimalist aesthetic is reflected not only in the artists her gallery represented—Judd, Carl Andre, and Dan Flavin—but also in her 1976 gift to the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts of a Dan Flavin work dedicated to Donald Judd (Fig. 14). In 1973, Lee opened a branch of her gallery in Houston. In spite of critical success, the Dallas gallery closed in 1974, while the Houston branch stayed open until 1983.

Delahunty Gallery also earned a reputation for bringing big names to Dallas. While Lee’s gallery emphasized nationally known artists, Delahunty maintained a strong connection to local and regional artists. Over the years the gallery presented exhibitions by Dallas-based artists George T. Green, Jim Roche, Gail Norfleet, Bob Wade, Lee Baxter Davis, Vernon Fisher, Raffaele Martini, Dan Rizzie, Debora Hunter, Nic Nicosia, Danny Williams, and James Surls. The connection to this local base was gallery director Murray Smither, who was well established in the Dallas art scene as director of Atelier Chapman Kelley, director of the Cranfill Gallery, and owner of the Smither Gallery before joining forces with Laura Carpenter and Virginia (Ginny) Gable at Delahunty in 1974. Operating at first out of Smither’s gallery at 2817 Allen Street, Delahunty soon moved to 2611 Cedar Springs Road. It remained there for several years until expanding into a new location in Deep Ellum in 1982.

Commercial galleries remained the driving force behind the art scene in Uptown through the 1980s and 1990s, with spaces like Edith Baker, Mattingly Baker, and Gerald Peters Fine Art exposing Dallas art lovers to current work by local, regional, and national artists. Edith Baker has had a long history of supporting art and artists in North Texas. She and her husband immigrated to the United States from Bulgaria in 1949, arriving in Dallas via Chicago in 1951. Edith took classes at the DMFA, studying under Octavio Medellín. In the 1960s, with the help of her husband, she opened her own studio behind their home, where she taught art classes. By 1977, Baker had stopped teaching and opened a gallery called Collector’s Choice with two partners in North Dallas near the intersection of Preston and Royal Lane. With a principal focus on decorative art and limited-edition prints, Collector’s Choice lasted until 1981, when the partnership ended. Baker renamed the space the Edith Baker Gallery, and by going out on her own shifted the focus to local artists, both emerging and established. In 1987, Baker moved her gallery to the Uptown area to be closer to the gallery district action. Baker retired in 2001 and handed over the reins to director Cidnee Patrick.

Aside from her gallery, Baker helped establish two organizations that focus on collaboration and community: the Dallas Art Dealers Association (DADA) and the Emergency Artists Support League (EASL). In 1985, Baker and 11 other gallery owners formed DADA as a way to encourage collaboration and synergy among the growing number of Dallas galleries (Fig. 15). Baker recalls the climate of the burgeoning gallery scene in the mid-1980s:

First of all, we never talked to each other. The galleries had no reason to talk to each other, and you didn’t know anybody. And so I think all of us were wondering what we could do, because I thought how other cities have their associations and we don’t have one. . . . We all had thought about it but June Mattingly was the one who assembled us into 12 galleries. . . . And the atmosphere changed . . . completely because we started communicating with each other.

Activities sponsored by DADA include twice-yearly art walks and the Edith Baker Scholarship Fund, named in Edith’s honor starting in 2005. Today, DADA has more than 30 members.

With local arts administrator and artists’ advocate Patricia Meadows, Baker created the Emergency Artists Support League (EASL) in 1992 to provide emergency grant funding to visual artists and visual art professionals in North Texas. Baker came up with the idea after seeing the Houston organization DiverseWorks come to the aid of local artist James Bettison following a series of misfortunes. When Dallas-based artists Nancy Chambers and Tracy Hicks each encountered health problems, the local arts community came together, with Baker and Meadows at the helm. A volunteer steering committee solicited donations in the first six months of EASL’s existence. Later fundraisers included an artist-designed coloring book (Fig. 16); the Tie One On benefit auction of artist-designed or -altered neckties in 1993; the Hats Off to EASL benefit auction of artist-designed or -altered hats in 1994; the Hot Flash benefit auction of artist-designed or -altered candlesticks in 1995; and the annual Art Heist, which started in 2006. Since 1992, EASL has given North Texas artists more than $320,000 in emergency funding. As Baker recalls,

EASL was the project that I'm really, really proud of. It is so difficult to help artists. We don’t know what to do for them. You know, it’s not like, “Here, let me give you some money.” This . . . was just a good project that really worked well for everybody and nobody could be more grateful than the artists. . . . Those moments of EASL, I think, were probably my best memories because we worked like Trojans, you know, to put up a show if we could get the space that we wanted.

DARE and The MAC

In 1994, McKinney Avenue Contemporary (The MAC) opened as a nonprofit space representing local, regional, national, and international contemporary artists. The MAC is the physical manifestation of several years of work by Dallas Artists Research and Exhibitions (DARE), which started in 1989 as a series of informal conversations between cofounders and friends Greg Metz and Tracy Hicks. Their talks led to organized meetings involving like-minded artists and covering topics like the need for greater art media coverage, ways around the “stagnant gallery scene,” and gaining greater exposure. At the heart of many of the discussions was the need for an organization to nurture and support serious, experimental artists of any medium and provide an alternative voice in the Dallas art community. As membership grew, so did DARE’s activities. In its first five years, the group organized the first Texas Biennial exhibition at the Fair Park Food and Fiber Pavilion; presented a Dialogue Series that brought national scholars and critics to Dallas, including preeminent modernist art critic Clement Greenberg; organized a rally in support of the National Endowment for the Arts (Fig. 17, Fig. 18); and published a newsletter covering the Dallas art scene and the group’s activities. DARE also developed a strong relationship with the Dallas Museum of Art through its director Richard Brettell and earned a seat at Museum board meetings, giving local artists a voice at one of the most exclusive tables in town.

In December 1990, DARE rented a warehouse on the edge of Deep Ellum as a place to curate exhibitions and performances for local artists, but the space at 605 South Good-Latimer Expressway needed serious renovation. In early 1994, local arts patron Claude Albritton offered to renovate a one-story 18,000-square-foot building at the corner of McKinney and Oak Grove Avenues in Uptown, rent the space to DARE for $1 per year, and contribute a $100,000 programming budget. DARE was absorbed into The MAC, having achieved its goal of creating an organization that nurtures contemporary artists. Since its opening, The MAC has exhibited more than 275 artists, continues its lecture series, and sponsors an in-house theater company, the Kitchen Dog Theater.

Uptown in the New Millennium

Uptown maintained its status as the gallery district of Dallas through the new millennium. Important gallery spaces like Pillsbury & Peters Gallery, Afterimage, Dunn and Brown Contemporary, and Photographs Do Not Bend kept the area alive with regular exhibitions of contemporary art by local, regional, and international artists in a variety of media.

As the neighborhood’s oldest running gallery and the city’s first dedicated photography gallery, Afterimage continues to offer exhibitions of local and international photographers organized by owner and founder Ben Breard. Every Christmas, a large group exhibition features prints from the gallery’s stock. Breard and Afterimage were also founding members of the Dallas Art Dealers Association.

Dunn and Brown Contemporary was established in 1999 by former Gerald Peters Fine Arts director Talley Dunn and Lisa Hirschler Brown in a former design warehouse at the north end of Uptown. At Gerald Peters since 1993, Dunn had developed a strong group of collectors while establishing relationships with the gallery’s artists, many of whom followed her to Dunn and Brown: David Bates, Julie Bozzi, Vernon Fisher, Annette Lawrence, Nic Nicosia, and Linda Ridgway. The first exhibition at Dunn and Brown, titled Inaugural Exhibition, featured Helen Altman of Fort Worth, Matthew Sontheimer of Houston, and Liz Ward of San Antonio. The exhibition program gave regular solo shows to stable artists and brought in exhibitions by artists of international renown. During its 12-year run, Dunn and Brown gained a reputation for supporting established and emerging local and regional artists. Brown left the partnership in 2011 to work as a private art consultant, and Dunn continued the gallery in the same location under her name. In addition to solo exhibitions by stable artists, Talley Dunn continues to bring in international exhibitions, including shows of Philip Pearlstein and Helen Frankenthaler in 2011 and a major Dale Chihuly retrospective in 2012 that featured work installed in the gallery and at the Dallas Arboretum.

As an alternative to Afterimage Gallery, Photographs Do Not Bend (PDNB) focuses on 20th-century and contemporary photography and photo-based art. Owned and operated by Burt and Missy Finger since 1995, the gallery represents recognized artists from the United States, Latin America, Europe, and Asia. Also featured are artist monographs and out-of-print photography books. In 2005, PNDB relocated to its present location in the Design District, joining former Uptown galleries Craighead Green Gallery, Gerald Peters Gallery, and Pan-American Gallery.

The gallery migration to the Design District left Uptown with fewer options for viewing contemporary art. The neighborhood as a whole has transitioned in recent years to a lively dining and entertainment destination for young professionals. The number of residential properties has increased, and restaurants, bars, and nightclubs line McKinney Avenue and Cedar Springs Road. The West Village property development at Lemmon and McKinney Avenues further adds to the neighborhood’s attraction. Two anchor spaces—Talley Dunn Gallery and The MAC—maintain the neighborhood’s vital connection to local art communities. With the addition of Klyde Warren Park connecting Uptown to the Arts District, the opportunities for exchange between these two neighborhoods are only beginning.