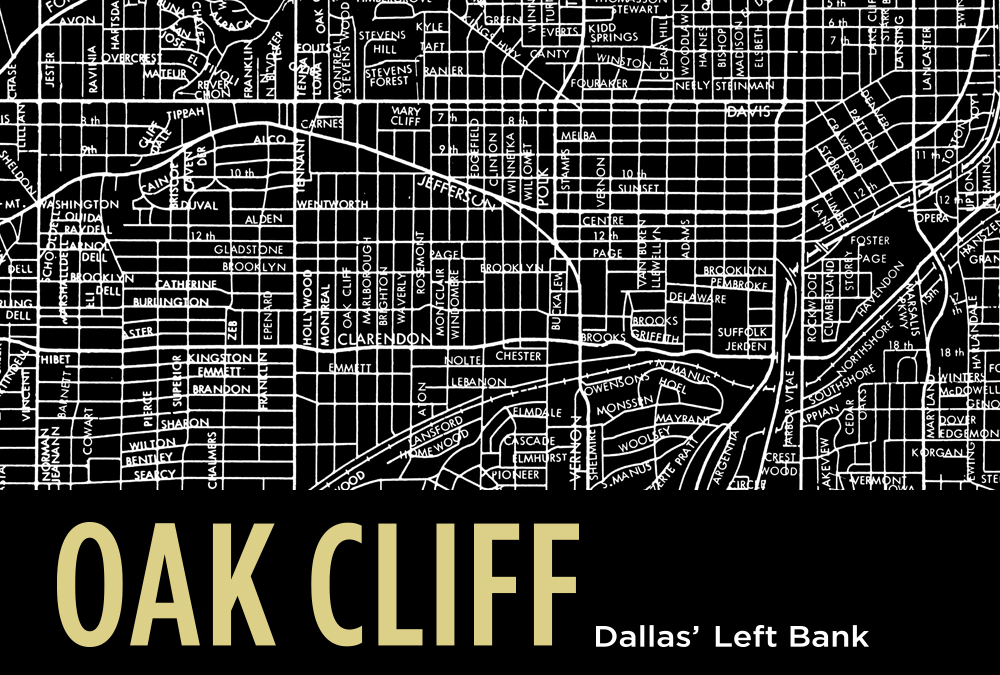

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Oak Cliff became a lively creative enclave, earning its nickname as Dallas’ Left Bank. Local artists discovered opportunities in the available, affordable homes and former businesses in the declining area, and as they created studios and live-work spaces there in the late 1960s, the neighborhood blossomed as an arts community. Visual artists like the Oak Cliff Four moved in to live alongside Oak Cliff natives—actors and musicians like Yvonne Craig, Stevie Ray Vaughn, and T-Bone Walker. They followed earlier generations of artists, including Texas regionalist Frank Reaugh (1860–1945), who moved to Dallas in 1890 and established a studio in Oak Cliff, and Velma (1901–1988) and Otis Dozier (1904–1987), whose home was a frequent meeting place for Otis’ students from Southern Methodist University.

Bordered today by the Trinity River and interstate highways 30 and 35E, Oak Cliff was a separate town until it was annexed by the city at the turn of the 20th century. Historically, the neighborhood was a wealthy suburb, popular with upper-middle-class residents for its rolling hills and lush green landscapes. Though Oak Cliff has officially been part of Dallas for more than a century, people who live there have reveled in their outsider status, taking pride in a place that has the feeling of a small town nestled within a big city.

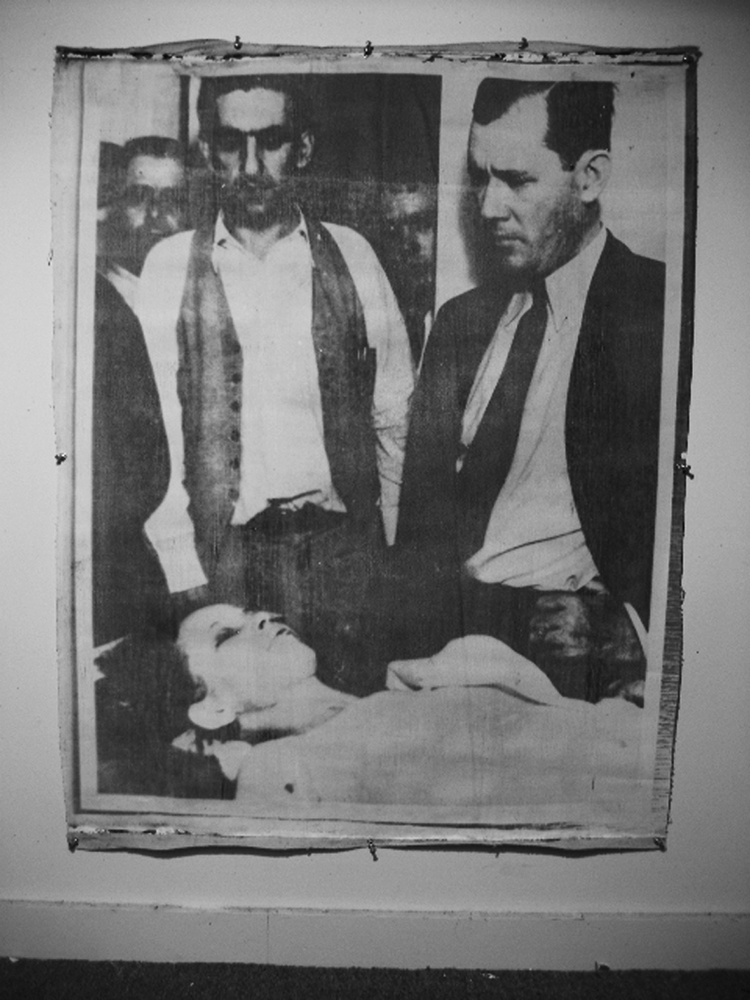

Oak Cliff has had a few notorious residents, including Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow and Lee Harvey Oswald. Oswald’s connection left a stain on the neighborhood in 1963. He was apprehended there in the historic Texas Theatre, near the boarding house where he lived, after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy downtown and the shooting death of Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit in Oak Cliff. These events—and the fact that Oswald’s killer, Jack Ruby, was also an Oak Cliff resident at the time—influenced the neighborhood’s reputation as a “lawless, useless zone.”

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964, South Oak Cliff was one of the first neighborhoods in Dallas to begin integration. African-American residents could now live in affordable, attractive homes in stable communities—a far cry from the overcrowded, crime-ridden conditions in South Dallas and State Thomas, where racist law and tradition dominated. The shifting racial demographics of Oak Cliff led to decreasing property values and large-scale white flight, as more and more white property owners left their homes vacant and moved to the developing suburbs in North Dallas. During this transition, Oak Cliff gradually fell into decline. While the area experienced a resurgence of activity when artists began moving there in the 1970s and 1980s, its artist communities remained stuck in the segregated past. There was little comingling then between African-American artists living in Oak Cliff—including Arthello Beck Jr. and Frank Frazier—and artists who relocated there in search of affordable space. Beck’s gallery remained focused on showing the work of African-American artists, and new galleries that opened in the late 1980s and early 1990s—such as Ann Taylor Gallery, Visions in Black, and Ebony Fine Arts Gallery—kept this racial focus. As the demographics have shifted in recent years to include a large Latino population, the Ice House Cultural Center and Steve Cruz’s Mighty Fine Arts have contributed to the growing diversity of the artist communities of Oak Cliff.

Oak Cliff Artists: 1970s

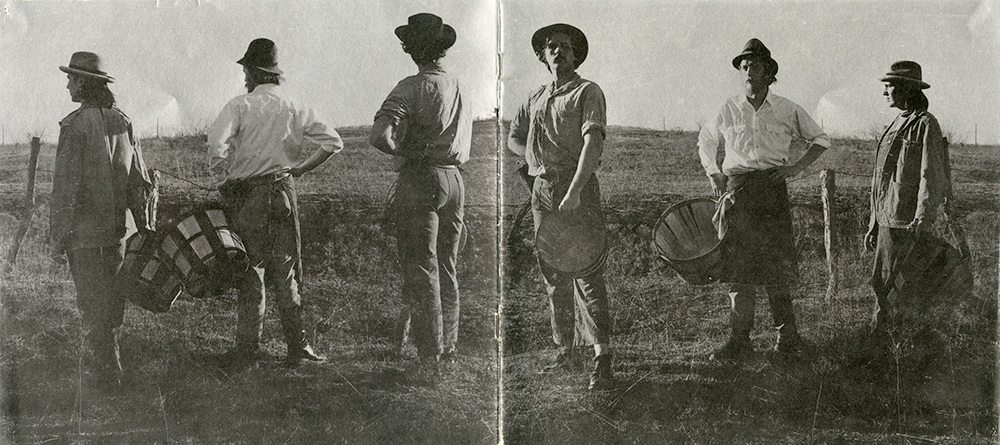

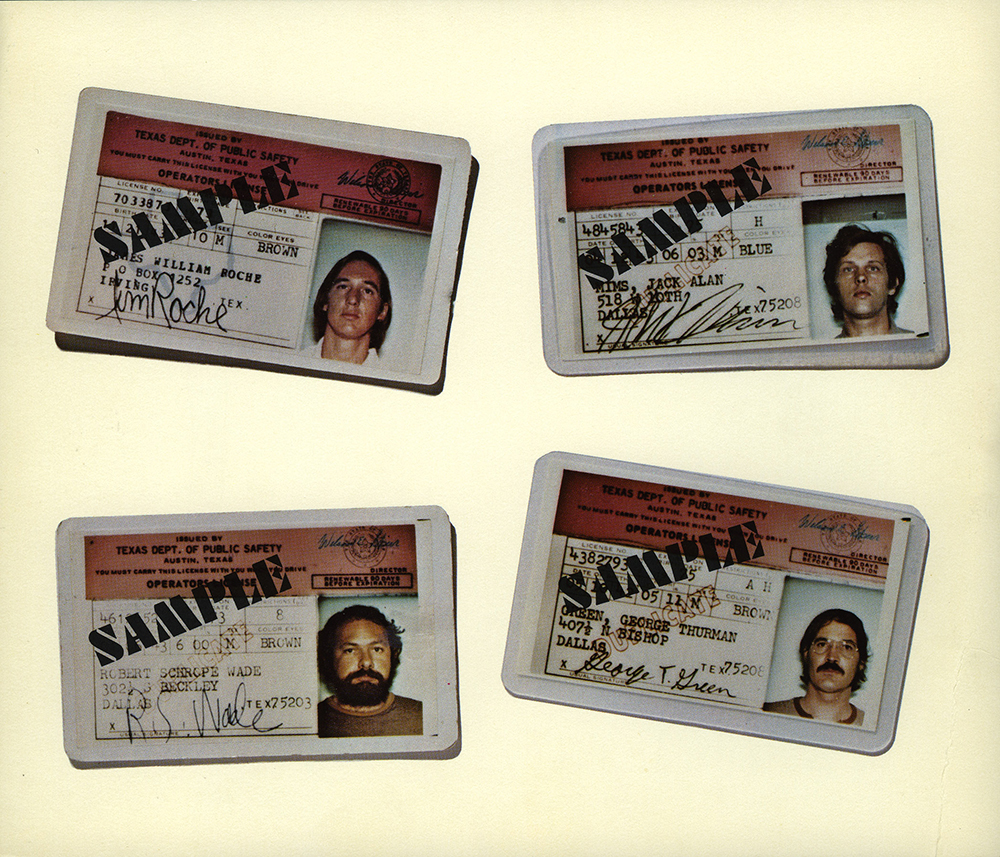

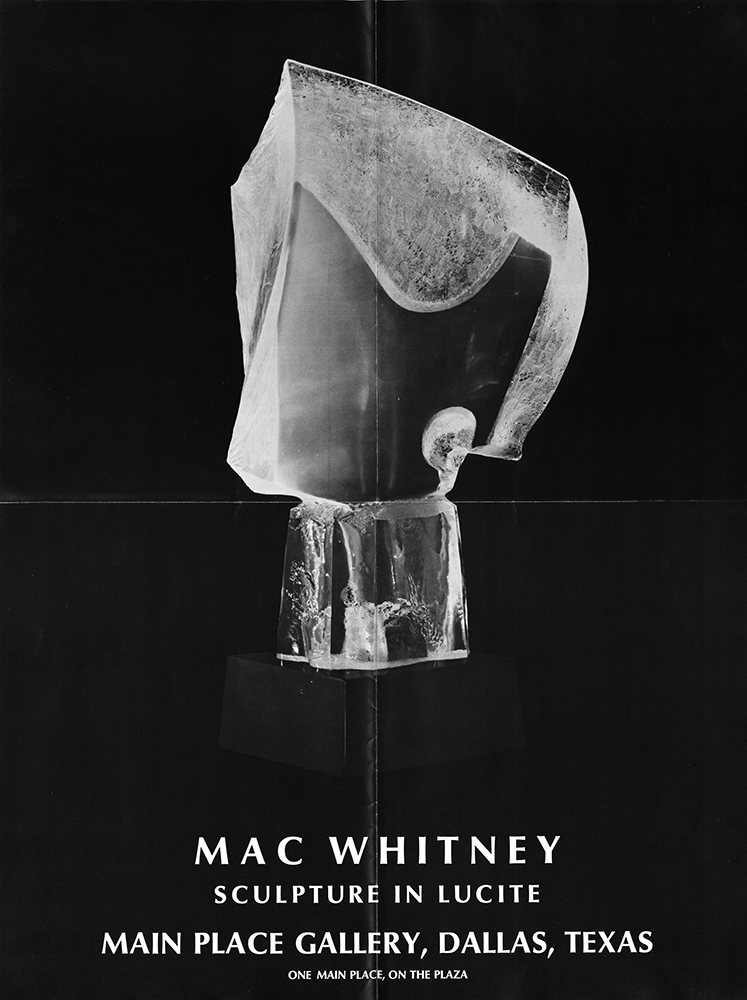

Artists George T. Green, Jack Mims, Jim Roche, Mac Whitney, and Robert (Daddy-O) Wade had all established studios in Oak Cliff by 1970 (Fig. 1). Living across the Trinity River from most of the art activity in Dallas, they took advantage of the freedom that comes with relative isolation. They were all about the same age, and nearly all were southerners by birth. Mims, Roche, and Green met as students in the MFA program at the University of Dallas. Though Mims was born and raised in Oak Cliff, Whitney was the first of the group to move there as a professional artist. Arriving in Texas in 1969 for his first solo exhibition at One Main Place (Fig. 2), Whitney established his studio in a two-story brick home next to a vacant lot near the Oak Farms Dairy (Fig. 3) and later moved to a ranch-style family home a few blocks from where Oswald shot Officer Tippit. Following Mims’ 1970 MFA thesis exhibition for UD, which was installed in the lobby of One Main Place (Fig. 4), he set up a studio in a home he inherited from his grandmother. With Mims’ encouragement, Roche followed, and then Wade moved into a converted loft space on the corner of Beckley Avenue and Jefferson Boulevard. Green moved into the area around Bishop Avenue and Eighth Street, now known as the Bishop Arts District, and combined several empty apartments into one huge space. Though Whitney lived near Green, Mims, Roche, and Wade and was part of their famous chili dinners at Wade’s studio, his loner mentality and strikingly different approach to his work separated him from the core group, who would become known as the Oak Cliff Four.

Artists working in Oak Cliff gained national attention when Newsweek featured them in a 1972 article titled “Big D.” It focused on Roche, Green, and Sam Gummelt just after an exhibition of their work at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts. A single, iconic image depicted four artists in Wade’s studio, with the caption, “Dallas artists Roche, Green, Mims, and Wade: Chili and bravado” (Fig. 5). Though the article never clearly defined a group, it may be the reason Roche, Green, Mims, and Wade were singled out as the Oak Cliff Four. A year later, the Oak Cliff Four had a group exhibition at the Tyler Museum of Art (Fig. 6, Fig. 7), solidifying their status as a four-man collective. Later in 1973 they had a group show at Dennis Hopper’s gallery in Taos, New Mexico.

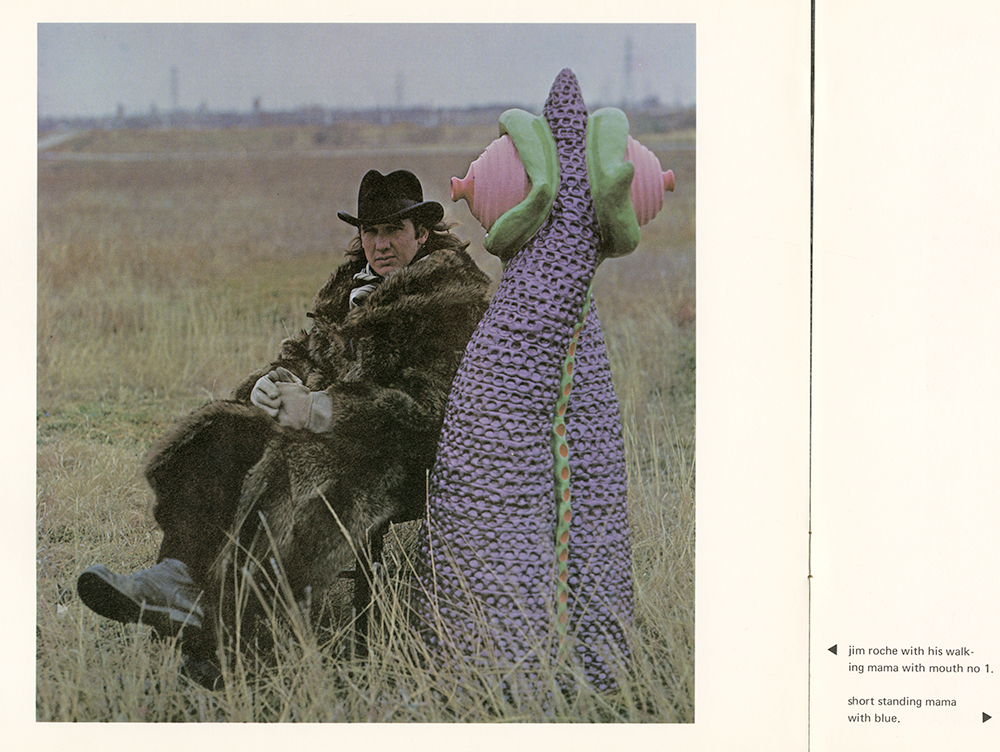

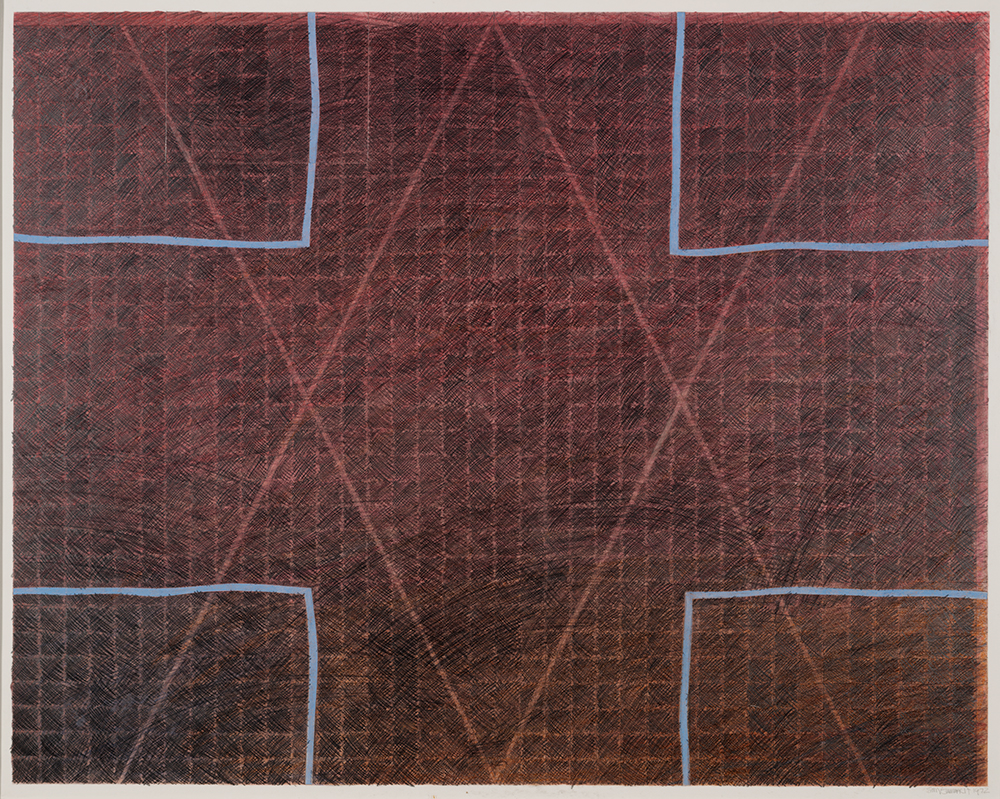

Looking at their work, it is not immediately apparent what Green, Mims, Roche, and Wade had in common. But they all drew on Texas mythologies for their subject matter in ways that became characterized as a certain style of Texas Funk. Hailing from Buddy Holly’s birthplace of Lubbock, Texas, Green was heavily influenced by 1950s nostalgia and referenced the kitschy culture of the time: Holly and rock-and-roll, drive-in movie theaters, cars, and 1950s household fixtures and decor. He constructed sculptures using out-of-date linoleum as his material (Fig. 8), as well as drawings in which cockroaches anthropomorphize as human characters with Texan costumes. Roche’s busty ceramic “mama plants” and ink-on-mylar drawings narrated the dysfunctional culture of Texas (Fig. 9, Fig. 10), while Mims’ more traditional practice of painting focused on symbolism with ominous overtones (Fig. 11). Wade’s work most directly reflected his surroundings, producing photo emulsion canvases that portrayed outlaws and social misfits like Bonnie and Clyde, Lee Harvey Oswald, and Jack Ruby (Fig. 12).

Though the Oak Cliff Four never thought of themselves as a collective, the group leveraged the popularity of their recently anointed brand and presented a united front as “part of a general movement . . . that was decentralizing the art world and breaking up the Minimalist hegemony.” The artists enjoyed wide-ranging local support, with galleries like Cranfill Gallery, Atelier Chapman Kelley, Janie C. Lee Gallery, and Delahunty Gallery giving them solo exhibitions. Henry T. Hopkins, director of the Fort Worth Art Center Museum (now the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth), and Fort Worth Star-Telegram arts critic Jan Butterfield furthered the group’s cause on a national level.

The four artists disbanded around 1974 when their individual careers took on greater importance. In 1973, Roche accepted a position at Florida State University in Tallahassee, and Mims followed a year later. Wade received a National Endowment for the Arts grant that year to realize a massive project: collecting objects, signs, memorabilia, and memories from across the country to install in his Bicentennial Map of the United States in North Dallas in 1976. This 300-foot-wide earthwork, which reflected Wade’s interaction with Robert Smithson at the Northwood Institute, included billboards touting, among other things, Tandy's Radio Shack and Big Boy Hamburgers, an Old Faithful water fountain from Wyoming, a telephone booth from Chicago, and 12 miniature skyscrapers courtesy of Continental Steel. The work caught the attention of People magazine, which featured Wade in its issue celebrating the U.S. Bicentennial.

Northwood Institute’s Contemporary Arts Program

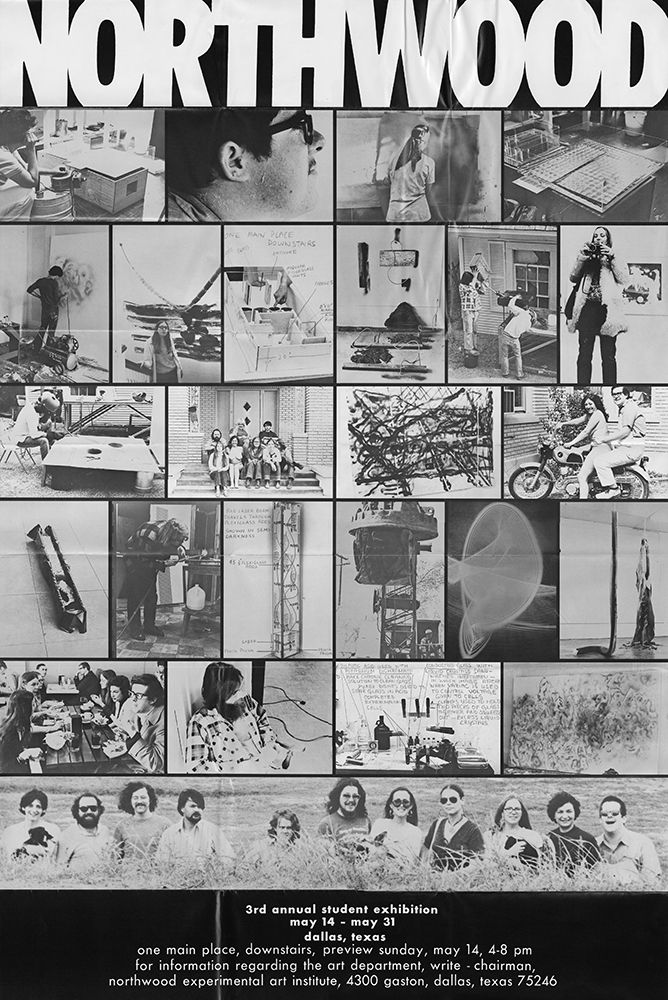

While living in his Oak Cliff studio, Bob Wade made trips back and forth to his teaching gig at a small, business-oriented, two-year college in far South Oak Cliff called Northwood Institute (Fig. 13). With a main campus in Midland, Michigan, by 1969 Northwood had branches in West Palm Beach, Florida; Cedar Hill, Texas; and Skowhegan, Maine. The specialized curriculum was “developed in cooperation with business and industry” and focused on “imparting new concepts of usable knowledge for use in today’s world through creative teaching and close association of the learning with the doing.” With the belief that its learning-by-doing strategy should also apply to the visual arts, Northwood introduced a contemporary arts program at the Dallas-area campus in 1968. While short lived, the program brought nationally recognized artists like Robert Smithson, Keith Sonnier, Italo Scanga, Alan Shields, and Billy Al Bengston to Texas. It also became an outlet for leading minds in the arts community, including Betty Blake, Evelyn Lambert, Chapman Kelley, and Henry Hopkins, to focus their energy on making great things happen in the underrecognized Dallas arts scene. The combination of art and technology put the program at the forefront of contemporary art practices, giving students hands-on experience working with engineers from Dallas-based Texas Instruments to create works of art using innovative technologies.

Since the merger of the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts with the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1963, many people involved with the DMCA and the local art scene had been looking for ways to promote contemporary art in Dallas. With the new Northwood Institute Experimental Contemporary Arts Program, they looked to the Cedar Hill campus as a center for this emerging interest (Fig. 14). The program offered a visual arts curriculum culminating in a two-year associate’s degree. Courses included art history, painting, life drawing, sculpture, and electives in filmmaking, photography, graphic design, and theater design. Teachers were practicing professional artists, and the campus regularly welcomed visiting artists.

Local artist and gallery owner Chapman Kelley, who offered his services as an advisor, developed the initial idea for the program at Northwood, and in 1969 Kelley and his wife established the first scholarship fund for students. In its first year, the program enrolled 22 full-time students and three part-time students. Facilities on the Cedar Hill campus included a workshop, a display area, offices, a library room, a museum display area, and storage, along with studios for students and the director of education, Alberto Collie (Fig. 15). Students used materials like “laser beams, magnetic water, fiber optics, neon, polyurethane foam, polyurethane sheets, rock (natural), metal, environmental chambers, and stroboscopes.” Among the guest lecturers in the first year were Vassilakis Takis, Len Lye, Howard Wise, and Kenneth Snelson. Mr. and Mr. Joseph O. Lambert Jr. of Dallas gave the Northwood Institute one of Snelson’s large metal sculptures, which was installed outside the Lambert Commons building on campus and later temporarily installed in the lagoon at the DMFA in Fair Park (Fig. 16).

Despite the local success of the program, Northwood executives wanted national reach and visibility, so they appointed former DMCA director Douglas MacAgy as chairman of the contemporary arts advisory committee of the Northwood Institute of Texas. MacAgy—at the time a top official at the federal National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C.—called together personal friends and colleagues from the art world for the first advisory committee meeting in May 1970. They included some of the nation’s leading museum directors: Walter Hopps of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (later founding director of the Menil Collection, Houston); Leon Arkus of the Carnegie Institute Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Sebastian Adler of the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; and Henry Hopkins of the Fort Worth Art Center Museum. Among the other members were Victor D’Amico, director of education at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Robert Kaupelis, artist and professor of art at New York University; Carl Feiss, counselor on planning and urban design for the American Institute of Architects; and Rev. Roger Ortmayer, director of the department of church and culture, National Council of Churches of Christ, New York. Local committee members who attended were Alberto Collie, sculptor and director of the Northwood Contemporary Art and Experimental Art Institute; Paul Baker, director of the Dallas Theater Center; Betty Blake Guiberson, gallery owner; Chapman Kelley, artist and gallery owner; Lawrence Kelly, director of the Dallas Civic Opera; and Mrs. Clint Murchison Jr.

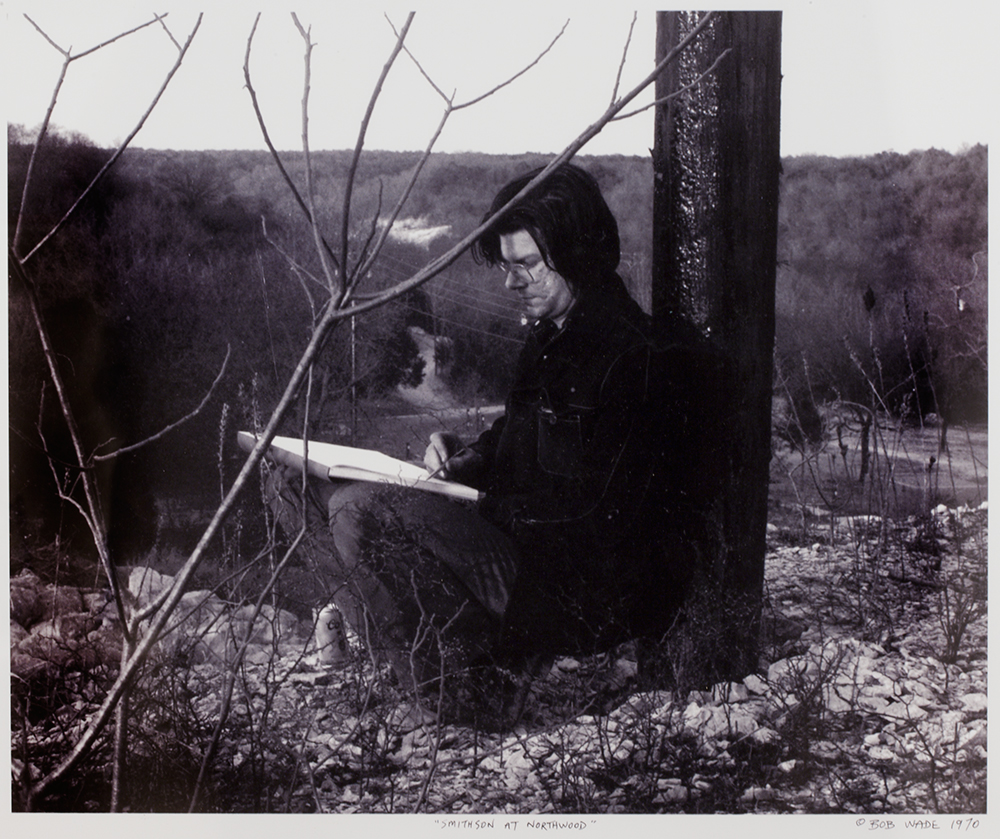

The committee changed the program’s name to the School of Contemporary Arts and discussed moving it to downtown Dallas, but decided that a campus location was more advantageous for students. Aspirations for the program were high, and it seemed to have a sound base of local and national support. Chapman Kelley contacted a group of well-known artists—including Philip Guston, Roy Lichtenstein, and James Rosenquist—about their interest in being visiting artists, and many of them were intrigued. But none of those on Kelley’s ambitious list ever made it to Northwood, and the little available material on the program suggests that the most famous artist to visit the campus was Robert Smithson, who arrived in late 1970.

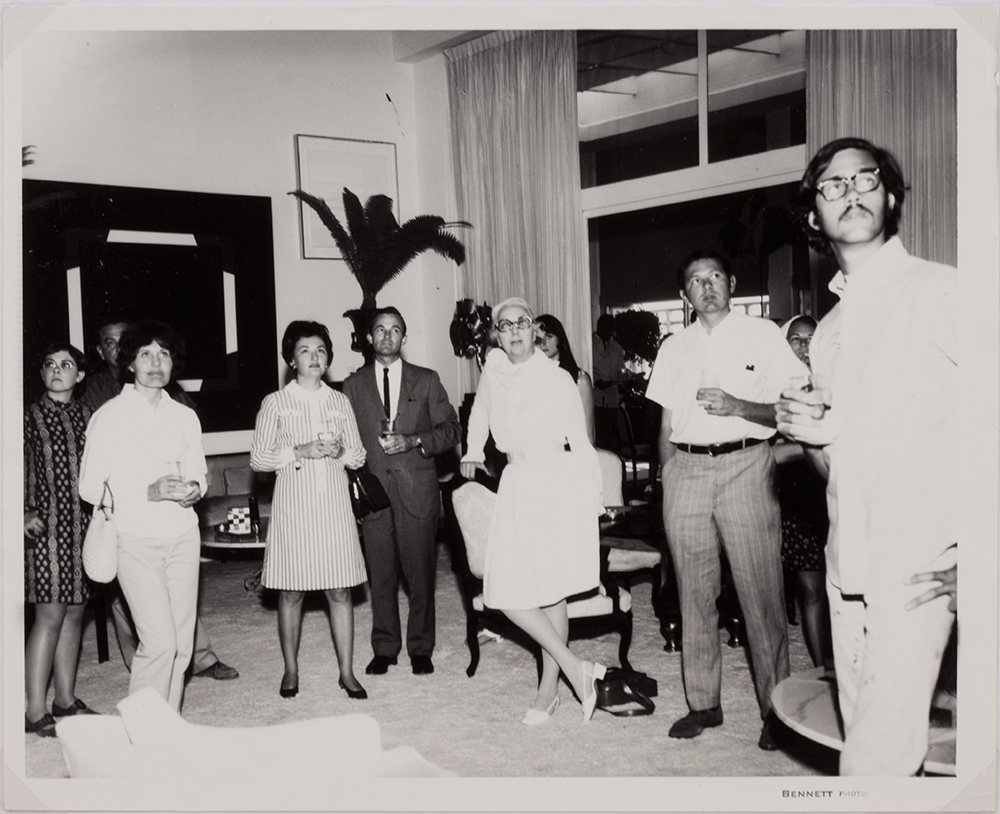

During his weeklong visit, Smithson gave lectures to students and showed his recently completed film Spiral Jetty to students, faculty, and guests at the home of Betty Blake Guiberson. He also scouted out property on campus that appealed to him as a potential site for one of his signature “pour” works. Smithson did a series of nine drawings illustrating his ideas for the earthwork Texas Overflow, 1970 (Fig. 17, Fig. 18). The drawings also serve as a storyboard for a film documenting a sculpture/earthwork that was never completed. As former Northwood student and future gallery owner Eugene Binder recalls:

I remember he [Smithson] really didn’t have this outgoing personality, which is something I ended up seeing with Donald Judd. These people [artists] had . . . this vision and they had their work, and this was an important thing. And while they wanted to project it out into the world, they also . . . had their share of naysayers. There was a certain concentration that they had that was very interesting to me in their presence, and that was getting it done. I remember Smithson being kind of aggravated, I guess, because people didn’t jump up and say, “Yeah, I want to be a part of this!” . . . I know that there was a sort of disappointment, like, “okay, I made my pitch and it’s not happening here.”

Other artists who visited the Northwood Institute included painters Larry Zox, Christopher Wilmarth (Fig. 19), and Billy Al Bengston (who had exhibitions at the Janie C. Lee Gallery in Dallas during their visits), constructivist sculptor George Rickey, and light sculptor Keith Sonnier. Exhibitions of student work and major collections were installed in Lambert Commons, a new building dedicated to Mr. and Mrs. Joseph O. Lambert Jr., major Northwood benefactors who were instrumental in founding and developing the program. In March 1971, selections from the collection of Mrs. Harry Lynde Bradley of Milwaukee were on view, giving students, local artists, and residents the opportunity to see more than 50 major works of modern art. The Lambert Commons gallery stayed open seven days a week to allow ample time for visitors to see this important collection.

After the success of the Bradley exhibition, the contemporary arts program moved in 1972 to Downtown Dallas (Fig. 20, Fig. 21), where students would have easier access to the local art scene and be fully immersed in the culture of emerging artists just down the street in Deep Ellum. The new location at 4300 Gaston Avenue at Peak Street also came with a new director: Bob Wade. But after just four months in this location, Northwood Institute’s executive officers decided to move the program back to the Cedar Hill campus. Wade resigned soon after.

Funding problems continued to plague Northwood’s contemporary art program, and despite lofty aspirations and apparent support, it was doomed. Only a few months after the May 1970 advisory committee planning meeting, the president and vice president had expressed their concern over the program’s slow start. When MacAgy died in September 1973 and Hopkins left Fort Worth for San Francisco that same year, the program lost its greatest advocates. The advisory committee dissolved, and the contemporary arts program closed sometime the following year. Northwood Institute still had an interest in combining business with the arts. From 1974 through the 1980s, the Michigan campus offered seminars on arts management and circulated them among its satellite campuses.

Oak Cliff through the 1980s

Creative activity in Oak Cliff was relatively quiet by the 1980s. The Creative Arts Center of Dallas, established by a group of local arts patrons in 1965 in the studio home of early Oak Cliff artist Frank Reaugh, had been a vital presence during its 20 years in the neighborhood, but it moved to the Kramer Elementary School building in East Dallas in 1982. This community center offered classes in theater, sculpture, painting, drawing, and ceramics taught by area artists, along with exhibitions of work by instructors and visiting artists. Local sculptor Octavio Medellín, a former teacher at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts Museum School, established the Medellín School of Sculpture at the center in 1966.

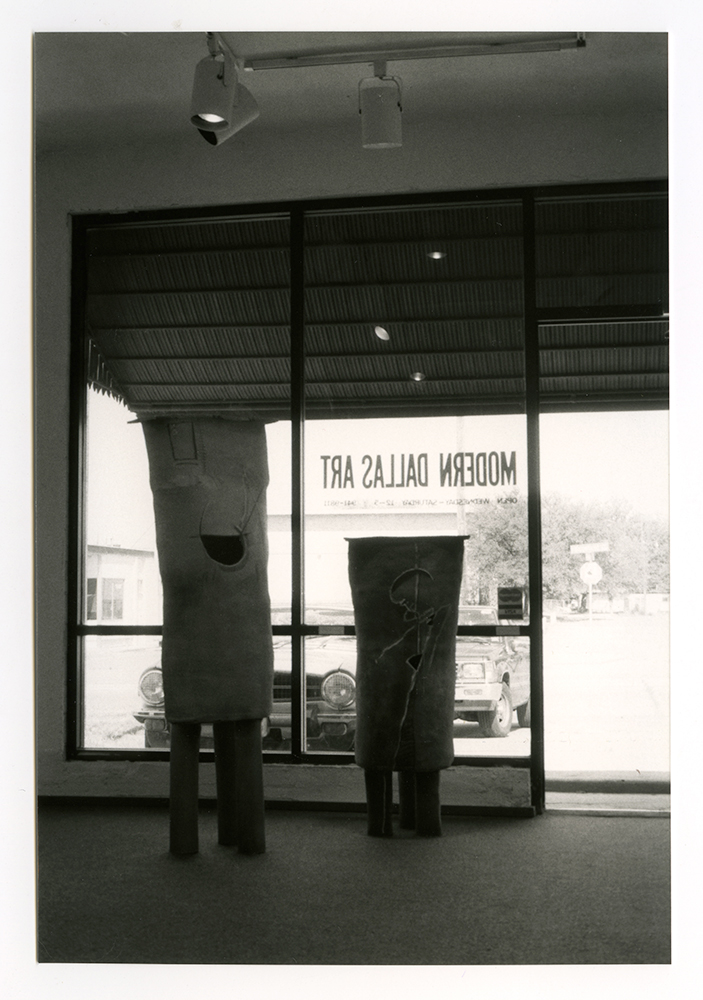

The few galleries remaining in the neighborhood tended to cater to diverse audiences. Arthello Beck Jr.—a member of the Southwest Black Artists Guild and a founder of the Association for Advancing Artists and Writers, Inc.—had established the Arthello Beck Gallery in 1974 in his home on Ramsey Avenue. His gallery featured the work of his friends and colleagues active in Dallas’ African-American arts community, such as photographer Carl Sidle and painters Nathan Jones, Jean Lacy, B. D. Norman, and Walter Winn. The gallery Modern Dallas Art had a successful run, attracting Dallasites across the river to Oak Cliff. Founded in 1986 by Glenn Lane and his partner Tim Thetford, its artists included Tony Holman, Rhea Burden, Gwen Norsworthy, Olya Cherentsova-Collins, Charlene Rathburn, Bob Nunn, Meg Loomis, Norman Kary, and George Moseley (Fig. 22, Fig. 23). It closed in 1990.

During the 1980s, local artists again began revitalizing parts of the neighborhood. Greg Metz, Bill Haveron, and Randy Twaddle moved into the vacant storefronts now known as the Bishop Arts District and jump-started the gentrification of the popular area. The concentration of notable Dallas artists living in Oak Cliff—including Tom Orr, Frank X. Tolbert 2, and Ann Lee Stautberg—inspired the creation of the bi-annual Oak Cliff studio tour (Fig. 24).

But artists also felt the negative impact of gentrification. In both Oak Cliff and Deep Ellum, the presence of artists in the community attracted nightclubs, and restaurants. Before long, developers sought a piece of the action. Eventually artists were priced out of neighborhoods they had helped to rejuvenate. By the mid- to late 1980s, developers had purchased many of the buildings Metz and his friends had renovated in the Bishop Arts District, sending them out to hunt for new space. Metz’s winning entry in the 1985 Oak Cliff Kinetic Sculpture parade was created in protest over the never-ending quest for space to live and work. The requirements for the judged competition were simple: original, “people-powered” works made of moving parts (Fig. 25, Fig. 26, Fig. 27). Metz’s Artist Wheel of Misfortune—an oversized hamster wheel powered by the artist running inside it—was adorned with a sign that read, “Oak Cliff used to raise artists and chickens. Now they only raise the rent (Fig. 28).”

South of the development in the Bishop Arts District, African-American artists were creating opportunities of their own. Ann Taylor Gallery, established in 1988 in the Westcliff Mall in South Oak Cliff, was the first of the new galleries to feature their work. In 1989, three more galleries opened: Ebony Fine Arts Gallery, Roots Gallery (in Deep Ellum), and Visions in Black. These spaces catered to the predominantly African-American residents of Oak Cliff, offering them the opportunity to see and be inspired by the work of African-American artists.

Into the 21st Century

Oak Cliff welcomed its first official cultural center in 1997 with the opening of the Ice House Cultural Center in a 1908 building at 1004 West Page Street. Part of the City of Dallas Office of Cultural Affairs, it was a Latino-focused venue to promote arts and cultural events that reflect the diversity of Oak Cliff and surrounding neighborhoods. The center closed in 2009 and reemerged in 2010 as the Oak Cliff Cultural Center in a new location next door to the historic Texas Theatre. It has an art gallery and multipurpose studio and offers workshops, musical performances, dance classes, and summer camps for all ages. The gallery is open to exhibition submissions and has hosted exhibitions such as La Genta de la Revolución (November 2010–January 2011), historic photographs that document the Mexican Revolution; XXI: Conflicts in a New Century (April 2011), a group photography exhibit curated by locals Charles Dee Mitchell and Cynthia Mulcahy; and Oak Cliff in Transit (July–August, 2012), a “visual homage” to the neighborhood through paintings and conceptual works by Mathew Barnes, Rosie Lee, and Orlando Sanchez.

The neighborhood welcomed its first artist residency in 1998 with Art Landing, established by Rachel Stirewalt and her husband J. D. Varnell as a combination gallery, workspace, and residence. The couple renovated the old warehouse, which accommodates up to 12 artists in its vast 11,000-square-foot space. In 2005, La Reunion TX (LRTX) was established on 35 acres in West Oak Cliff. In this nontraditional residency, artists are invited to create site-specific ephemeral works in tune with the natural environment, based on the premise that “art and artists are critical to a thriving community . . . [and] need a chance, from time to time, to recharge their creative spirit.” Regular programs include Art Chicas, which teams high school students with established artists; Found Object Art, a partnership with the Nasher Sculpture Center and the Dallas Independent School District; and Environmental Art, an annual juried program in which local artists to create works using materials from the LRTX grounds.

As Oak Cliff entered the 21st century, spaces like Mulcahy Modern and Mighty Fine Arts continued the neighborhood’s tradition of representing work by diverse emerging local and regional talent. Today Oak Cliff claims more artists per capita than any neighborhood in the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. In 2005, artists living and working there began organizing the Visual Speed Bump Tour, an annual open-studio event involving as many as 15 studios and spaces. Artists like Kim Cadmus Owens, Scott Winterrowd, Gretchen Goetz, Erik Tosten, Duke Horn, and artist duo Chuck & George (Brian K. Jones and Brian K. Scott) offer the public a glimpse into their world, while galleries and art spaces like Oil and Cotton, the Davis Foundry, and the Lilco Press also welcome visitors.

The neighborhood of Oak Cliff continues to enjoy a vital art scene, maintaining its focus on creating connections through a strong sense of community. Its many artists and creative spaces make it a destination for art and culture, while it retains a sense of history through original buildings like the Texas Theatre, the Belmont Hotel, and the Wynnewood Shopping Center. Unlike neighborhoods that boast major institutions or glamorous galleries, Oak Cliff truly feels as though it is run by the artists themselves.