By the early 1960s, the Dallas area boasted five major university art departments: Texas Woman’s University, the University of North Texas, the University of Dallas, the University of Texas at Arlington, and Southern Methodist University. That number grew steadily for the next 15 years, as the Dallas County Community College District campuses, the University of Dallas, and the University of Texas at Dallas all created art programs. These higher education communities cultivated freedom of expression in young artists, who were encouraged to test the boundaries of art under the guidance of seasoned professors.

The first of these programs was established in 1901 as one of the original five departments at what is now Texas Woman’s University (TWU). The University of North Texas (UNT) offered studio art courses as early as 1894 and began awarding master of science degrees by the mid-1930s. The University of Texas at Arlington (UTA), founded in 1923 as North Texas Agricultural College, began awarding degrees in the arts in 1959.

Art programs at other major universities in the Dallas–Fort Worth area emerged in the 1960s. At Southern Methodist University (SMU), the School of Music expanded in 1964 to become the Meadows School of the Arts, granting degrees in the visual and performing arts and eventually in communications. The University of Dallas (UD, founded in 1956) received a major gift in 1966 to create the Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts, which awarded master of fine arts degrees to fully funded students. In 1975, the University of Texas at Dallas (UTD, founded in 1969) invited artist and professor Will Hipps to start an art program that quickly became a vital addition to the area’s university arts community.

The trend in North Texas followed the nationwide growth in college and university art departments after World War II, stimulated in part by the surge in attendance created by the GI Bill. Major artists of the postwar generation—including Robert Rauschenberg, Donald Judd, Cy Twombly, and Jasper Johns—used the bill to pay their way through college. Another contributing factor was the influx of refugees throughout the war and into the Cold War years. Some of Europe’s most illustrious artists, who arrived seeking sanctuary and new audiences for their art, earned a living as teachers in emerging art programs. Higher education institutions were eager to use the considerable talents of artists like George Grosz, who taught at the Art Students League of New York and the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa; László Moholy-Nagy, who helped start the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937; and György Kepes, who established the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1967. Changing perceptions of art also prompted the creation of art programs. As American art captured greater interest and recognition, the center of the art world shifted from Paris to New York City, and as the professional artist gained elevated status, universities wanted to provide advanced-level education in art.

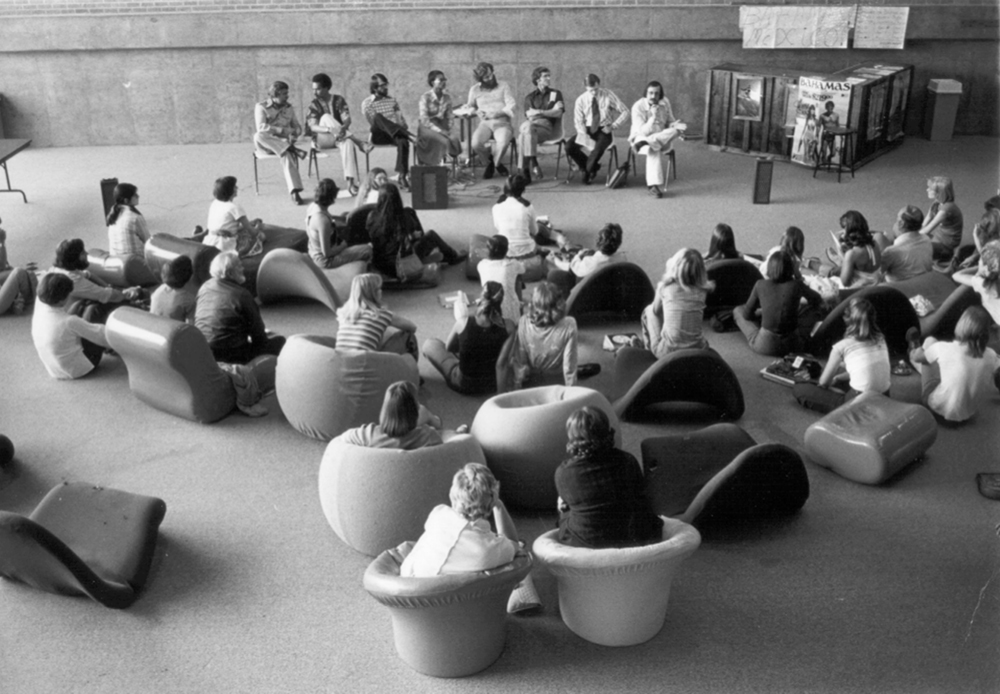

By the 1960s, community colleges (or junior colleges, as they were called then) expanded to add courses in studio art to their traditional vocational curriculums. The growing cost of higher education generated a demand for two-year trade schools that were stepping-stones to further education. World conflict again played a role in the developing educational system, as many junior colleges attracted young men seeking to avoid the draft during the Vietnam War. The Dallas County Junior College District was established in 1965, with El Centro College opening in downtown Dallas as its first campus in 1966. The Eastfield (Fig. 1) and Mountain View campuses were established in 1970, and soon the remaining campuses—Richland (1972, Fig. 2, Fig. 3), Cedar Valley, North Lake (1977, Fig. 4), and Brookhaven (1978)—served neighborhoods and suburbs throughout Dallas County.

Artists as Teachers

With the creation of so many art departments in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, professional artists were in demand to lead these programs. Artists came from all over the country to teach. TWU had several notable female artists on its faculty, including photographer Carlotta Corpron (1901–1988), who worked with László Moholy-Nagy and György Kepes during their visits to Texas in the 1940s, and Dorothy Antoinette “Toni” LaSelle (1901–2002), who studied painting with Hans Hofmann in Provincetown, Massachusetts, in the 1940s and 1950s and with Moholy-Nagy at the New Bauhaus. In more recent years, photographer Susan kae Grant joined the faculty at TWU in 1981. Now professor and head of photography and book arts, Grant established the first book arts specialty in the area while developing her career as a professional artist. Arthur Koch was recruited in 1966 from a teaching post in Washington State to teach studio art courses at El Centro College. Soon after, he began a 40-year teaching career at SMU, working with Dallas newcomers Laurence (Larry) Sholder and Roger Winter. Winter arrived in Dallas in the late 1950s. He worked first at the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts and as a teacher at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts and the Julius Schepps Community Center. Jerry Bywaters, the former DMFA director who was then head of the SMU art department, invited Winter to teach courses there. Winter recalls their conversations:

He asked me once, “Brother Roger, would you like to teach a photography class?” And I said, “I don’t know anything about photography.” And the next year, he asked me if I would like to teach a design class, and that was more interesting but I said, “No, I don’t think I would want to do that.” And then he asked me if I would like to teach a drawing class, and I said, “I would love to.”

Winter taught painting and drawing at SMU for the next 26 years. Nationally recognized artists like David Bates, John Alexander, and Dan Rizzie all credit his teaching as a source of inspiration. Bates, especially, says Winter gave him the freedom to pursue his own style:

It all started when Roger Winter—I was in his drawing class, one time, and everybody, I mean a lot of the kids could draw. They were really, really good at it. . . . I would be drawing the model and then I’d get tired of drawing that and then I’d draw you drawing the model. . . . It was a whole composition, and he came over and saw that all in colored pencils, and he said, “Come here. Come on, let’s go, you’re out,” and I went, “What?” He goes,” Get your stuff, let’s go.” He took me downstairs and put me on a Dallas city bus that went by SMU, paid for it, stuck all of the money in there to keep me on the bus all day, and he said, “You’ll be back about 4:30.” So, I’m like, “Okay.” He said, “Just draw what you see on the bus when you’re out there, just draw all of that stuff. It’s what you want to do anyway.” And I went, “Cool.”

I just sat on the bus and I was drawing all of these people getting on and off the bus, all of these characters, the bus driver, the inside of the bus, the whole thing, and when I came back with it, he was like, “That’s what I’m talking about.”

Adding to the energy at SMU, scholar William B. Jordan was invited to Dallas under initially unfortunate circumstances. Texas oilman and novice collector Algur H. Meadows had amassed a collection of Spanish Old Master paintings, which he donated to SMU in establishing the Meadows Museum of Art. Collected in large groups during the 1950s and 1960s, the paintings were acquired at suspiciously low prices. An evaluation revealed that they were for the most part falsely attributed. Dallas artist and gallery owner Donald Vogel conducted the initial evaluation with the help of fellow gallery owners and members of the Art Dealers Association of America. Refusing to believe that his collection was a bust, Meadows sought a second opinion from DMFA director Merrill Rueppel, who backed the dealer’s evaluation. In a final effort to save what he thought was a good collection, Meadows sought a third opinion from the preeminent scholar in Spanish painting Dr. José López-Rey, under whom Jordan had studied at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. It was determined that the collection, though it contained a few accurate attributions, was not good enough to form the basis of a museum. Unwilling to let this experience damper his passion for art, Meadows hired Jordan as director of the Meadows Museum at SMU, and together they established what many consider to be the most important collection of Spanish art outside of Spain.

As director of the Meadows Museum and chairman of the Art Department (1967–1980), Jordan oversaw the University Gallery and its exhibitions of contemporary art. He organized some memorable shows, including the collection of actor Dennis Hopper in 1971–1972, prominently featuring one of the motorcycles Hopper used in the 1969 film Easy Rider, along with masterpieces of postwar art by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Wallace Burnett. Other exhibitions—including Paintings and Drawings by Cy Twombly (1980) and Livres d’Artiste by Braque, Matisse, and Picasso from the Collection of the Bridwell Library (1980)—signaled a more scholarly approach to the study of contemporary art. Poets of the Cities: New York and San Francisco 1950–65 (1974), held concurrently at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, gave SMU students the opportunity to rub shoulders with stars of the international contemporary art scene. As David Bates recalls, it was a pivotal moment in his development as an artist:

The Dallas Museum brought a group that’s called Poets of the City and that show brought Merce Cunningham and Rauschenberg and John Cage and Robert Whitman, who I worked with. . . . They went over to SMU to get interns or dupes or whoever to come over there [the DMFA] and take them around and all of that. . . . You were just these young people that they hired on for these big guys that came to town and you were involved in their stuff, doing performances. That was a performance. That was before I went to New York; I was involved in a performance with Bob Whitman and Sylvia Whitman. Anyway, that was a show where you got to see real artists come in and do their bit, and the Fort Worth show was another deal where we saw these artists, again, imported in to do something about this place. Those kinds of things were really important to see as a young artist coming along.

At the University of Texas at Dallas—a technology- and science-based research university—Will Hipps oversaw the construction of the iconic Art Barn building, as well as the development of a unique interdisciplinary program that expands the boundaries of arts and technology by combining dance, music, and theater with the visual arts. As Hipps’ fellow art instructor and artist Frances Bagley explained: “We were charged with developing an entirely new, experimental curriculum unlike any in the area.”

In recognition of the new UTD program and the completion of the Eugene McDermott Library, library director James T. Dodson and Dallas Museum of Fine Arts contemporary art curator Robert Murdock organized a major invitational exhibition of contemporary sculpture in 1976. The show combined work by nationally recognized sculptors like Mark di Suvero, Donald Judd, and Beverly Pepper with work by local sculptors Jim Love, James Surls, Mac Whitney, and Raffaele Martini. Dallas Morning News critic Janet Kutner noted that “UTD is establishing itself as a vital and active part of the Dallas art community. The sculpture show is ambitious enough by itself. But it introduces what will probably be a program of at least one major show annually on the campus from this point forward.” While the exhibition was never repeated, it did help establish UTD as an important contributor to the North Texas art scene.

Vincent Falsetta relocated to Texas in 1977 to teach at North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas) and quickly got involved in the art community. He became a member of 500 Exposition Gallery (now 500X), showing his work in All-Star Stable (1979), Nexus in Texas: Exchange Show with Nexus Foundation for Today’s Art, Philadelphia, PA (1979), and a 1981 solo show. Falsetta’s brand of abstract painting was new to Texas, where the representational art of an earlier generation—Texas Funk, Bob Wade, and Jack Mims—was still the norm.

The University of Texas at Arlington’s Center for Research in Contemporary Art (CRCA), established in 1986, was a significant catalyst for the North Texas contemporary art scene. CRCA directors have included Jeff Kelley (1986–1990), Al Harris-Fernandez (1991–1994), and former DMFA contemporary art curator Sue Graze (1994–1996). In 1997, Benito Huerta was hired as director when CRCA was renamed The Gallery at UTA.

The gallery offered exhibitions and programs that began as social experiments, posing philosophical questions with answers in the form of exhibitions and programming—for example, the exhibition Memory (1988), which answered the question, “What if Dallas–Fort Worth artists were invited to create works of art about what they had remembered and forgotten of the Kennedy assassination?” or the performance Border Arts Workshop/Taller de Arte Fronterizo (1990), which answered the question, “What if artists working along the California-Mexico border staged a performance whose video images were transmitted into the gallery live over international phone lines?”

Artist Collectives

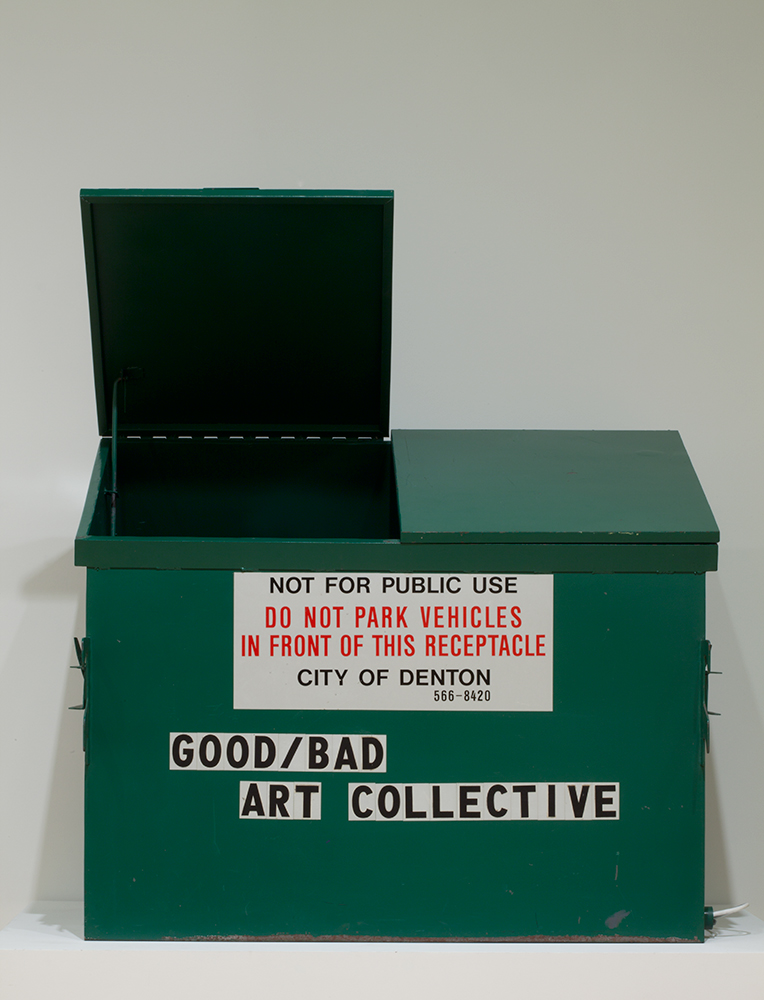

University communities were incubators for artist collectives, which helped emerging artists strengthen their work through discussion and exchange. The most talked-about group to come out of North Texas was the Good/Bad Art Collective, which began in 1993 with nine undergraduate and graduate students who were not satisfied with the level of creative support at UNT. The exception was UNT professor Vernon Fisher, who Good/Bad members considered a major influence. His course Hybrid Forms pushed students out of traditional media like painting and sculpture into a conceptual-based practice. Followers of the Fisher Method were a tight-knit group. They even reproduced a life-sized image of the professor’s face wearing a Mickey Mouse hat on a poster that hung on the walls of the Good/Bad’s building. Using social interaction as a framework for production, the collective staged about 250 one-night music and art events over nine years. Exhibitions like Very Fake, But Real at Diverse Works in Houston and Pena Heights at the Arlington Museum of Art represent the core of the Good/Bad method, which combined memorable audience interaction with elements of humor. Before the Good/Bad disbanded in 2001, it expanded to Brooklyn, New York, and held simultaneous events there and in Texas. The work created for these installations often was destroyed after the initial presentation (Fig. 5).

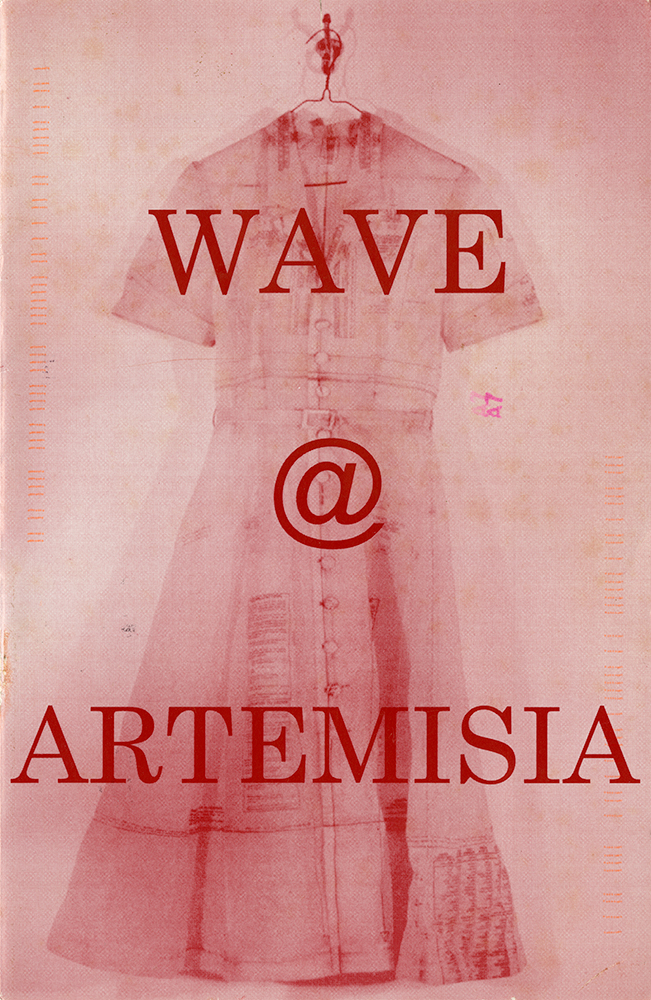

Another Denton-based collective was the all-female WAVE, established by artists from Texas Woman’s University in 1991. Describing itself as a professional artists’ forum, the group involved emerging artists seeking to increase exposure and exhibition opportunities, with the mission “to support women in the visual arts, to provide an environment conducive to open intellectual exchange, and to expand exhibition opportunities” (Fig. 6). WAVE exhibited primarily in Dallas, holding its first full membership show at 500X Gallery in 1992. Later exhibitions included Figs from Thistle at the J. Erik Jonsson Central Library in downtown Dallas (1992) and Out of Context, shown in Texas and in the Czech Republic (1993) as part of the 750th Anniversary Celebration and Festival in Brno at the invitation of Mayor Vaclav Mencl and the Moravian Provincial Museum. The exhibition featured WAVE’s visual interpretations of biblical references as a way of connecting art and language.

At the University of Texas at Dallas, new-millennium artists called themselves Oh6 Art Collective. Formed in the summer of 2004, the collective had 16 members who organized exhibitions at the Casket Factory in the South Side on Lamar building (Well, Red, 2004), Angstrom Gallery (Mission Control, 2005), and 500X Gallery (2006). Members included Elizabeth Alavi, Jerry Comandante, Shelby Cunningham, Tricia Elliott, Amy Halko, Sara Ishii, Adam Kobetich, Kirsten Macy, John Ryan Moore, Polly Perez, Aqsa Shakil, Erica Stephens, Raychael Stine, Tim Stokes, Kevin Todora, and Amber Wigant. In some ways, Oh6 was influenced by the mentality that the Good/Bad had perfected a decade earlier, as their exhibitions tended to be ephemeral, lasting for one night only.

Visiting Artists

Visiting artists have been vital contributors to art programs in North Texas, exposing students to national and international trends and movements. Tracy Harris, who received an MFA in 1983 from SMU, recalls that the art department brought in a visiting artist every few weeks to teach courses and have one-on-one time with students. Conceptual artist Mel Bochner, a particularly demanding teacher, encouraged emerging artists to think about their practice in new ways, stretching the notion of the meaning of art.

Other visiting artists took a hands-on approach. In 1984, internationally recognized minimalist sculptor Carl Andre spent a week in residence the Richland College campus of the Dallas County Community College District. He gave lectures and demonstrations, collaborated with students to create outdoor sculpture, and showed his work with area artists Frances Bagley, Jerry Dodd, Joy Poe, Manuel Mauricio, Sandy Stein, Linnea Glatt, Joe Havel, and Gisela-Heidi Strunck in an exhibition staged in three locations on campus.

In 1988, Jeff Kelley, founding director of CRCA, invited performance artist and happenings creator Allan Kaprow to the UTA campus to install his major retrospective exhibition Precedings (1988–1989). Kelley curated the show, which took the form of “reinvented” enactments of a dozen of Kaprow’s seminal happenings from 1959 to 1983, as well as four “lecture performances” by Kaprow. A daylong symposium included such illustrious art world citizens as Claes Oldenburg, George Segal, Richard Schechner, Barbara Smith, Michael Kirby, Moira Roth, Lucy Lippard, Ingrid Sischy, Jim Pomeroy, Robert Morgan, and Suzanne Lacy.

During her tenure as CRCA director, Sue Graze collaborated with UNT Art Gallery director Diana Block to bring the internationally renowned performance artist Marina Abramović to Dallas for exhibitions at both galleries. They included videos and photographs of Abramović’s past performances and wall rubbings from her 90-day walk along the Great Wall of China in 1988, as well as pieces from her “power objects” sculpture series. While in North Texas, Abramović created a new video work that was included in the Arlington installation of the show.

Notable Faculty and Alumni

Several current faculty members have long working relationships with the North Texas educational system, some for decades. While some are emeritus professors (Arthur “Robyn” Koch of SMU, Lyle Novinski of UD, and Vernon Fisher of UNT), other long-time faculty continue to offer courses and develop emerging artists into the future talent of North Texas. Annette Lawrence has taught at UNT since she moved to Texas in 1990. Greg Metz and John Pomara were originally considered a pair of Dallas “bad boys,” but they have been teaching at UTD since 1994 and 1996, respectively. Metz, Pomara, and Marilyn Waligore—photography professor at UTD since 1989—represent the trifecta of art disciplines, offering courses in sculpture and new media, painting, and photography.

The list of successful alumni from North Texas art departments is long and far-reaching. Breakout stars from SMU include David Bates (Eastfield, 1971–1973; BFA 1975, MFA 1978), who has been included in biennials at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (1984) and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1987). Bates enjoys a steady career, with representation on the West Coast and in Dallas at Talley Dunn Gallery. Dan Rizzie (MFA 1975) has exhibited extensively in New York and Texas. In the 1980s he was the subject of a national whiskey advertisement, appearing in magazines and on billboards all over the country.

The University of North Texas has also produced an impressive list of successful alumni. Nic Nicosia (BS 1974) was included in Whitney biennials in 1983 and 2000 and Documenta in 1992, and in 2010 he was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship. Nicosia’s work—like the work of many artists on this alumni list—is in the permanent collection of the Dallas Museum of Art. He remembers selling his photograph, River, 1981 (Fig. 7) to contemporary curator Sue Graze for a low negotiated price in 1981, when he was just shy of 30 years old. Other notable UNT alumni include Frances Bagley (MFA 1981), Jeff Elrod (BFA 1991), Brian Fridge (BFA 1994; UTD, MFA 2011), and Erick Swenson (BFA, 1999).

While some successful alumni have moved away from Dallas, others live and work as fixtures of the North Texas art scene. Tom Orr (El Centro, 1968–1970), Linnea Glatt (UD, MA 1972), Ann Lee Stautberg (UD, MA 1972), and Sherry Owens (SMU, BFA 1972) all have successful careers in Dallas. Many are represented by major galleries like Barry Whistler Gallery and Talley Dunn Gallery and serve as unofficial mentors to emerging artists who look to their careers as models.

Dallas’ university communities continue to draw top talent from around the region and nationwide. Their strength is reflected in the successful professional artists who are the product of this wide-reaching educational ecosystem, a driving force for contemporary art in North Texas.