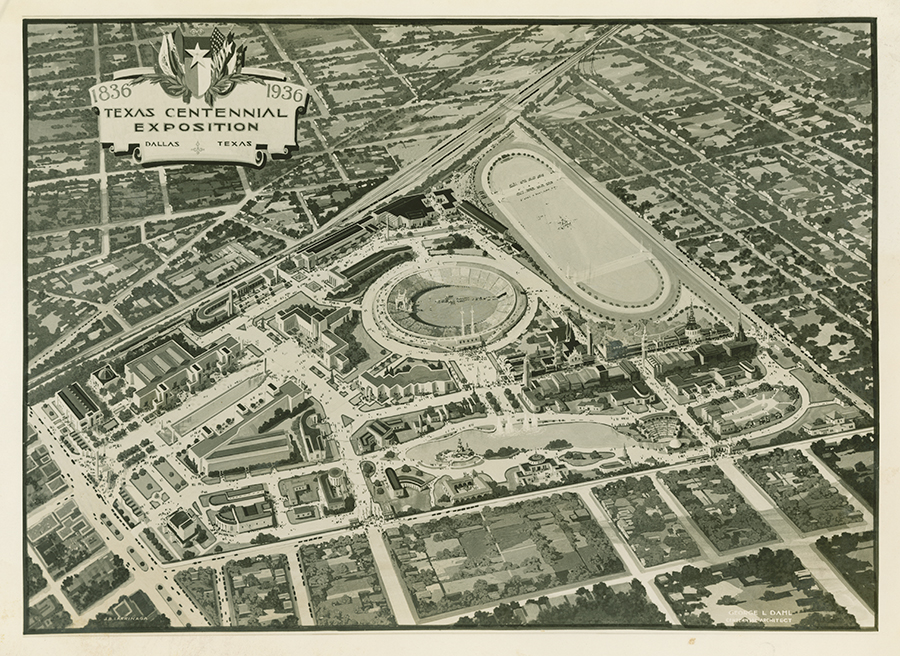

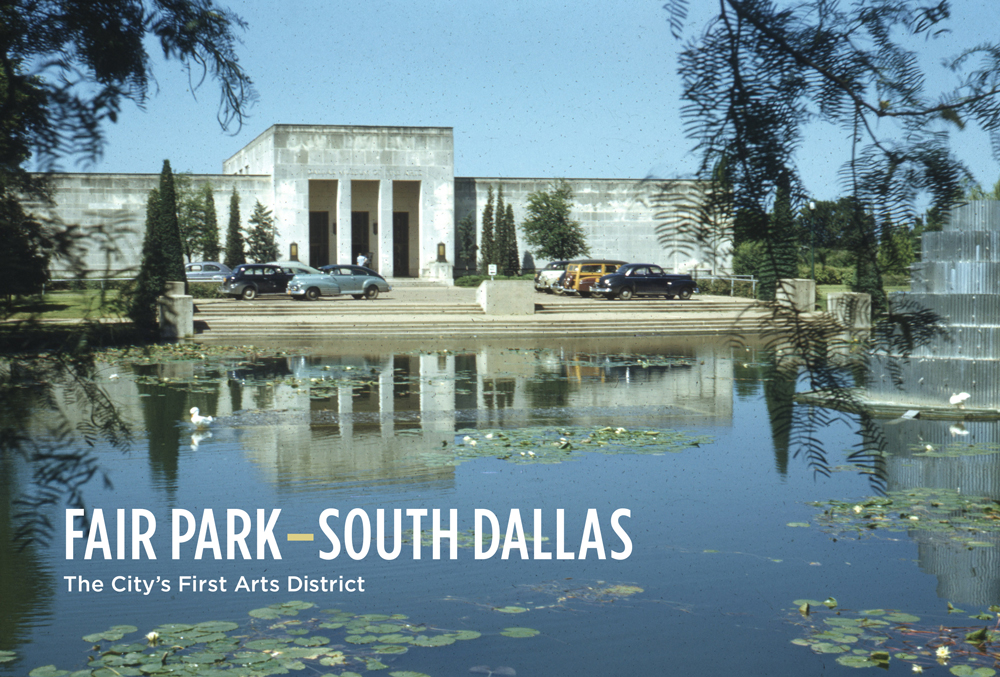

The history of contemporary art in Dallas has its roots in the Fair Park–South Dallas neighborhood, the city’s first arts district and a lively destination for art and culture. From the mid-1930s this area was home to North Texas’ finest cultural institutions, innovative galleries and alternative spaces, and a thriving community of artists. In a bid for the State Centennial Celebration in 1936, the City of Dallas expanded and beautified the county fairgrounds in South Dallas. Practically overnight, the city gained more than 200 acres of parks and dozens of art deco–style buildings, completed in time to host the event (Fig. 1). As part of the Fair Park expansion, permanent buildings were added to the grounds for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and the Dallas Art Association, governing body of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (DMFA) (Fig. 2). The Dallas Art Institute opened in the DMFA’s new building in 1938. In 1941, the official Museum School was established under the leadership of Museum director Richard Foster Howard, employing some of the state’s most recognizable artists as professors and offering classes in lithography, drawing, sculpture, ceramics, painting, and life drawing. The concentration of art and culture in Fair Park spilled into the surrounding neighborhood, attracting artists to live and work near the city’s cultural hub.

At its new home in Fair Park, the DMFA wasted no time in introducing the public to fine art. From the early 1940s through the 1960s, the Museum’s collecting and exhibitions reflected the interests of Jerry Bywaters, director beginning in 1943. Major exhibitions focused on Latin American contemporary art and local and regional art. Some exhibitions, including the landmark photography show The Family of Man and Some Businessmen Collect Contemporary Art, generated controversy in conservative McCarthy-era Dallas.

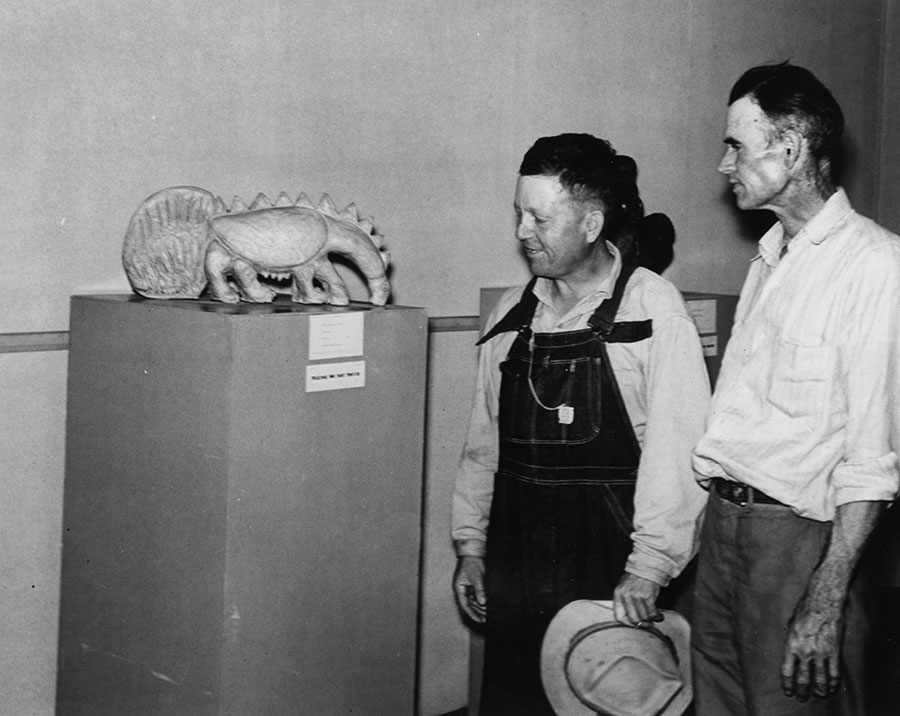

During peak periods, Fair Park was abuzz with activity, hosting stock shows, rodeos, horse racing, concerts, and football games. Attracting visitors was simply a matter of opening the Museum’s doors and advertising within the park, as events there helped increase attendance. Museum visitors were a diverse mix of area farmers, society women, and schoolchildren (Fig. 3), and the Museum did its best to accommodate its audience by gearing programming toward these groups. With the establishment of the Museum League in 1938, concerts, printmaking programs, children’s tours, and radio programs became a regular part of the DMFA, and in the early 1970s, members of The Assemblage, a young art collectors’ group, hosted Cowboy Brunches at the Museum before Dallas Cowboys football games to encourage the public to visit.

The most exciting time of year in Fair Park was the annual State Fair of Texas (Fig. 4). During the month-long celebration, hundreds of thousands of people would see the work of artists from all over the state in juried competitions like the Texas Annual Painting and Sculpture exhibition. Hosted by the DMFA and considered an accurate survey of the arts in Texas, these exhibitions emerged as early as 1928 with the First Allied Arts Exhibition of Dallas County. By the 1940s, the Texas General and the Southwestern Prints and Drawings exhibitions had been established. These competitive shows helped artists advance their careers through the validation that came from internationally recognized jurors. They also enabled the Museum to expand its collections by acquiring many of the prizewinning works.

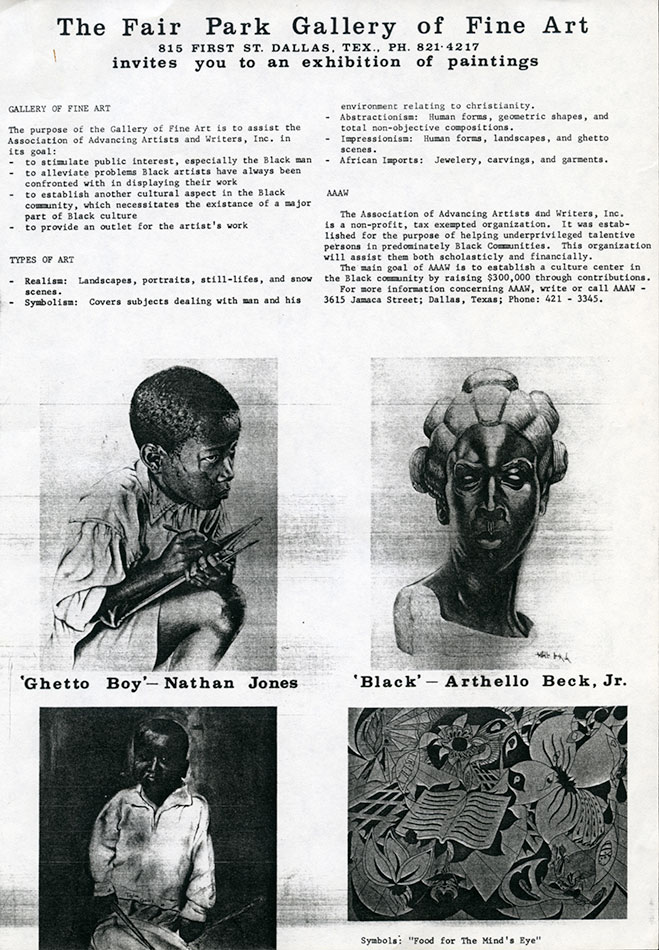

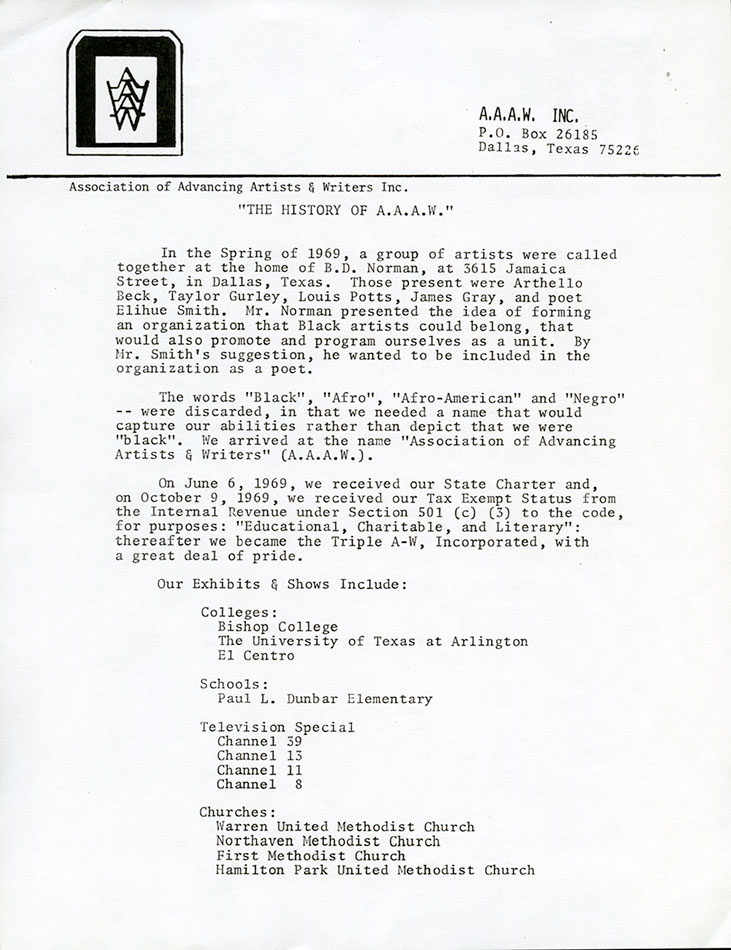

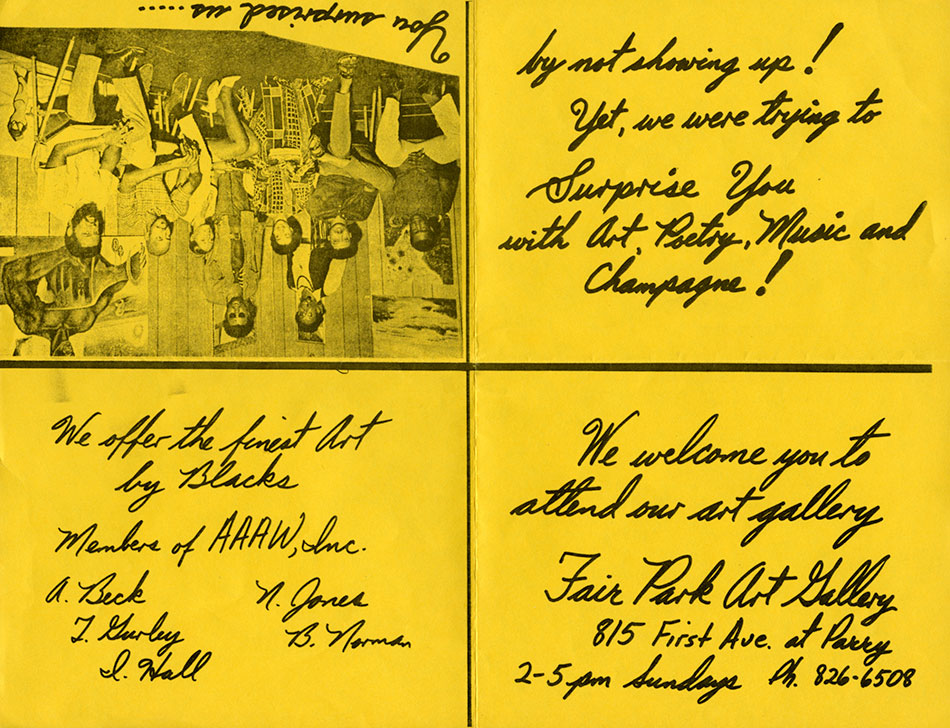

Arts activity in South Dallas was not limited to Fair Park. By the early 1970s, artists began moving into buildings facing the Music Hall at 909 First Avenue, renovating raw warehouses and vacant homes into live-work studios, alternative galleries, and cooperative spaces. Artists Arthello Beck and Nathan Jones were among the first, opening the Fair Park Gallery of Fine Art in a small house at 815 First Avenue in 1970 (Fig. 5). The gallery was the bricks-and-mortar location for the Association of Advancing Artists and Writers, Inc. (AAAW), an artist-run organization formed in the spring of 1969 to promote the work of African-American artists and writers. The founding members included visual artists Bobby D. Norman, Taylor Gurley, Louis Ray Potts, and James Gray and poet Elihue Smith. “We organized the AAAW in 1969 out of frustration which confronted black artists in their efforts to exhibit their work,” Norman explained. “After we got organized, poets and designers, and musicians and dancers all wanted to be in on it.”

Exhibiting opportunities for African-American artists in Dallas at the time were few and far between. An organization like the AAAW was crucial to encouraging and supporting these artists as they struggled to have their work shown in the still racially divided city. There were only a few local galleries, and they had rosters of predominantly white artists and were located in the historically white neighborhoods of Uptown and North Dallas. The problem of gallery representation persists to this day and goes beyond the lopsided gallery-to-artist ratio. As artist Vicki Meek explains, "African-American artists find themselves in a Catch-22 situation: If they are doing work that in any way expresses their ethnicity, they have placed themselves outside the mainstream. And what ‘mainstream' really means is ‘white, male art.’ Then you've got the other side, in that you don't have a strong black buying public. . . . There are few people on the black side who are willing to put the time and effort into it.”

The AAAW staged exhibitions at Bishop College, the University of Texas at Arlington, El Centro Community College, and churches in the South Dallas and Oak Cliff neighborhoods (Fig. 6). The opening of the Fair Park Gallery in 1970 gave the expanding membership a permanent space to work and to exhibit performance, written, and visual art (Fig. 7).

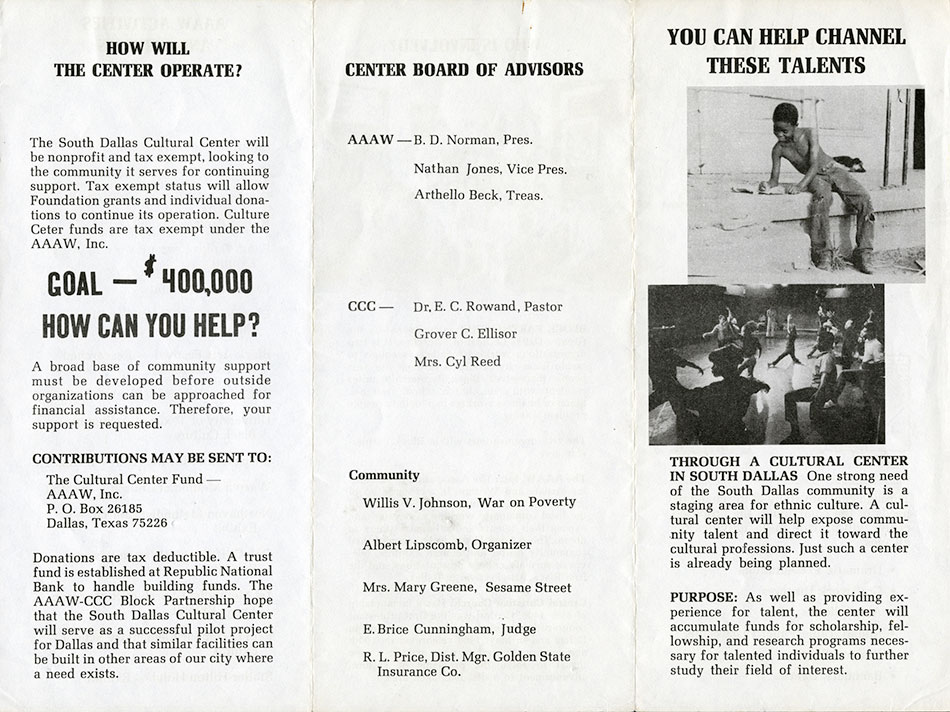

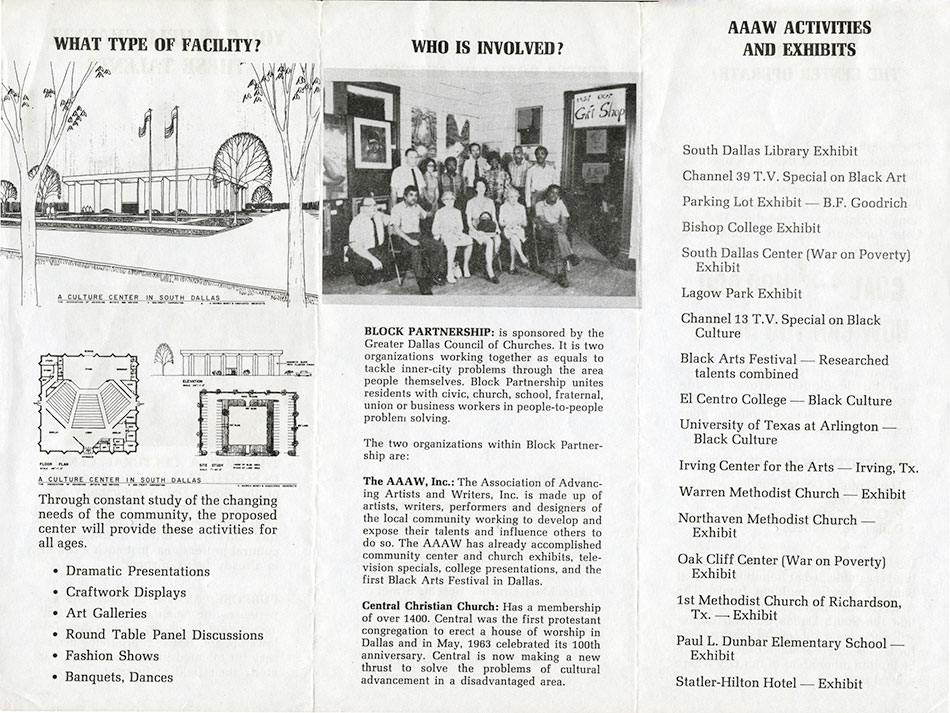

The AAAW also had a larger goal: establishing a cultural center in South Dallas that would broaden the exposure of African-American artists, writers, performers, and musicians. In 1971, the organization hosted a Black Arts Festival at the Fair Park Gallery as the first fundraiser for the proposed cultural center. Architect A. Warren Morey drew up plans, and for the next decade and a half, advocates continued to raise funds and awareness (Fig. 8, Fig. 9). But by the time the South Dallas Cultural Center opened in 1986, the AAAW had dissolved as a group.

In 1972, just down the street from the Fair Park Gallery, artists Richard Childers and David McCullough moved into a block of buildings at 842 First Avenue. Small businesses, bars, and restaurants occupied the street-level spaces, while the vacant second-level lofts offered thousands of available square feet (Fig. 10). Rent was low because the lofts usually had no modern amenities, so the artists had to install kitchen appliances, toilets, showers, air conditioning, and heating. But what these spaces lacked in comfort, they made up for in size and natural light.

Once Childers and McCullough completed the renovations in their space, more artists moved in to take advantage of the clean, well-lit galleries and live-work lofts. Known briefly as the 842 Collective, artists Gary Brotmeyer of New Orleans, Robin David of Atlanta, and Lanie Luckadeo and Andy Parks of Dallas, together with Childers and McCullough, worked in varying media and practiced transcendental meditation together as a way to move beyond individual egos and promote a spirit of collaboration. The 842s organized exhibitions that showcased their talents—including sculpture, performance, painting, and music—in their gallery, known as the AUM Gallery (Fig. 11). As the city’s first true alternative space, AUM filled a void in the Dallas art scene, as there were few exhibiting options available to artists not represented by commercial galleries.

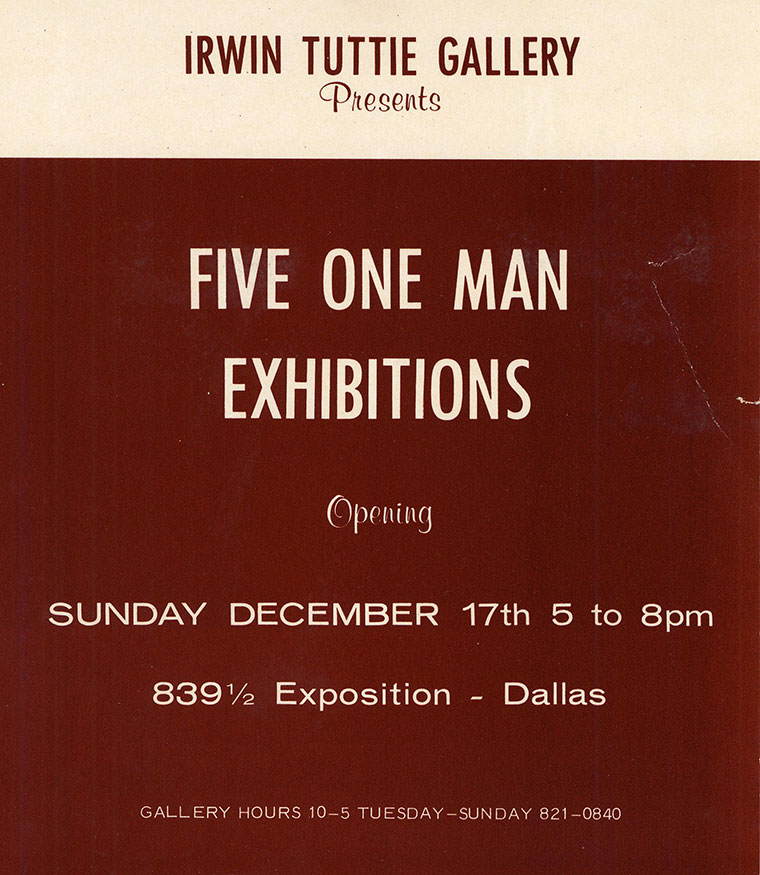

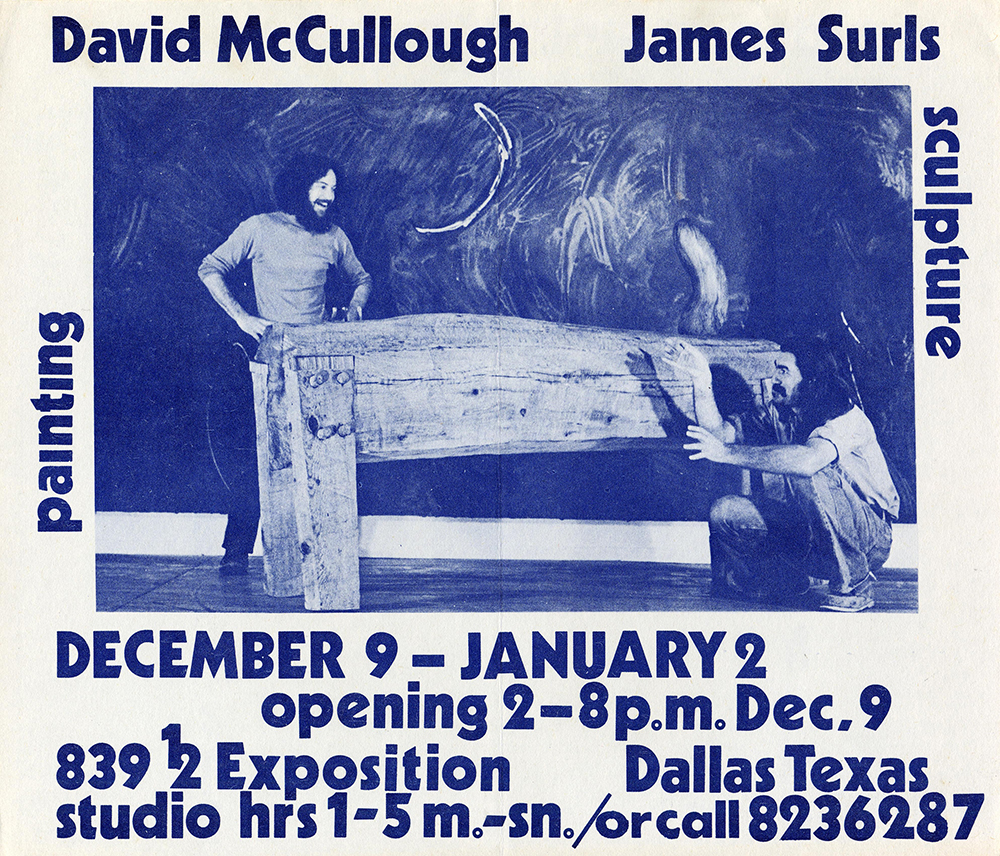

Before long, the energy surrounding the 842s spread to other local artists who were interested in developing alternative spaces of their own. For a short time, New York painter Irwin Tuttie lived in the second level at the corner of 839 1/2 Exposition Avenue, creating a space that operated more like a commercial gallery featuring exhibitions of local and regional artists (Fig. 12). Tuttie’s short-lived space was soon taken over when David McCullough decided to expand his own loft. McCullough renamed the location Oura, Inc., and with Dallas gallerist Ruth Wiseman, he launched a venue to stage exhibitions of his work and that of other emerging artists, notably James Surls (Fig. 13).

Individual artists like George Goodenow, Alberto Collie, and Mac Whitney also had studios in the neighborhood, adding to the energy and activity in South Dallas in the 1970s. As a response to this burgeoning artists’ community, Richard Childers, with artists Gilda Pervin and Stephen Grant, organized First Saturday Art in December 1975. On the first Saturday of every month, artists paid a small fee to exhibit in the loft space of 842 First Avenue. They were allowed to sell directly to the public, sidestepping commercial galleries and art dealers. First Saturday Art, Childers explained, was “an open opportunity for professional artists to show their works that will create overall high-quality exhibits and stimulate greater production and appreciation for the arts in Dallas.”

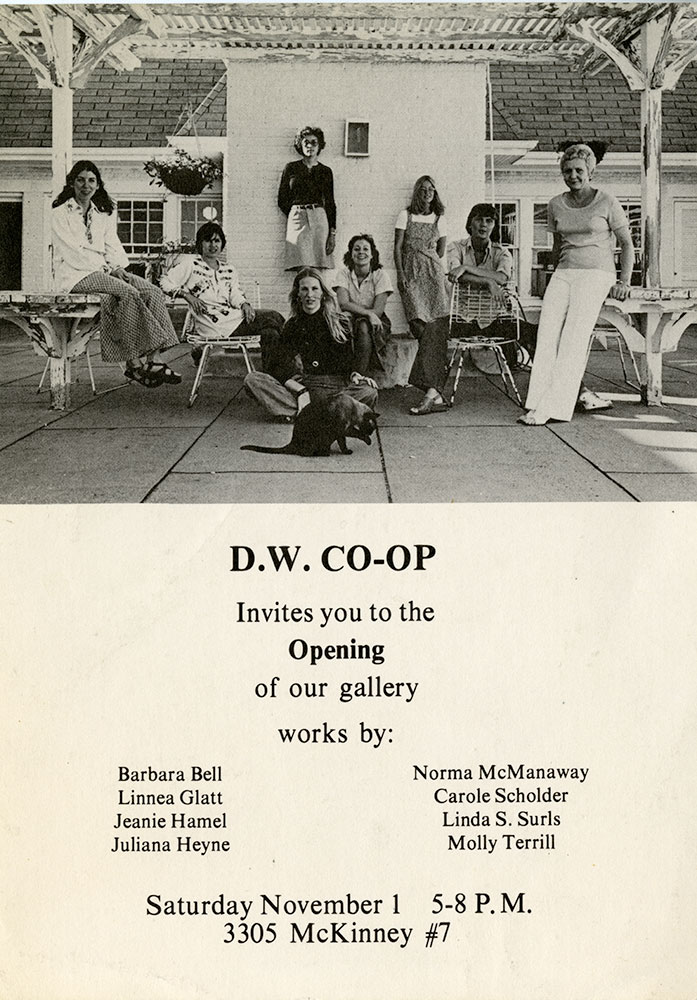

Exhibiting options in Dallas were limited when Childers introduced his concept. The DMFA had discontinued the annual juried competitions in 1976, and while a few local galleries, like Delahunty and Atelier Chapman Kelley, gave exhibitions to area artists, the art scene was still relatively small. Artists were taking opportunities into their own hands, and the popularity of the artist-run space continued to spread through other parts of town. Third Sunday, likely an inspiration for Childers’ First Saturday events, debuted in 1975 and enjoyed continued success in giving local photographers the opportunity to exhibit their work and sell directly to the public. A group of photographers interested in a venue dedicated to the promotion and display of photography organized the Allen Street Gallery in the Uptown neighborhood in 1975. Also in Uptown, eight artists established the Dallas Women’s Co-op (DW Co-op, later DW Gallery) in 1975 as an artist-run commercial gallery (Fig. 14). Rounding out this trend, Richard Childers and Will Hipps established what is now Texas’ oldest artist-run space when they purchased and renovated an old tire warehouse into a gallery/studio space. The 500 Exposition Gallery (later shortened to 500X) was established in 1978 on the far edge of Deep Ellum, just under the freeway from Childers’ longtime residence on First Avenue across from Fair Park.

As local artists developed an active arts community outside the boundaries of Fair Park, DMFA director Merrill Rueppel and curator of contemporary art Robert Murdock worked together to develop the Museum’s contemporary collection by acquiring masterpieces by international artists while maintaining connections to the local Dallas base. Shortly after his appointment in 1970, Murdock organized the exhibition Interchange with the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (Fig. 15). Three Dallas artists—George T. Green, Sam Gummelt, and Jim Roche—were paired with three Minnesota artists—Jerry Kielkopf, Jerry Ott, and Carl Brodie—to “provide opportunities for a decentralization of New York and Los Angeles art production and enable artists from different regions to exchange ideas” (Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18).

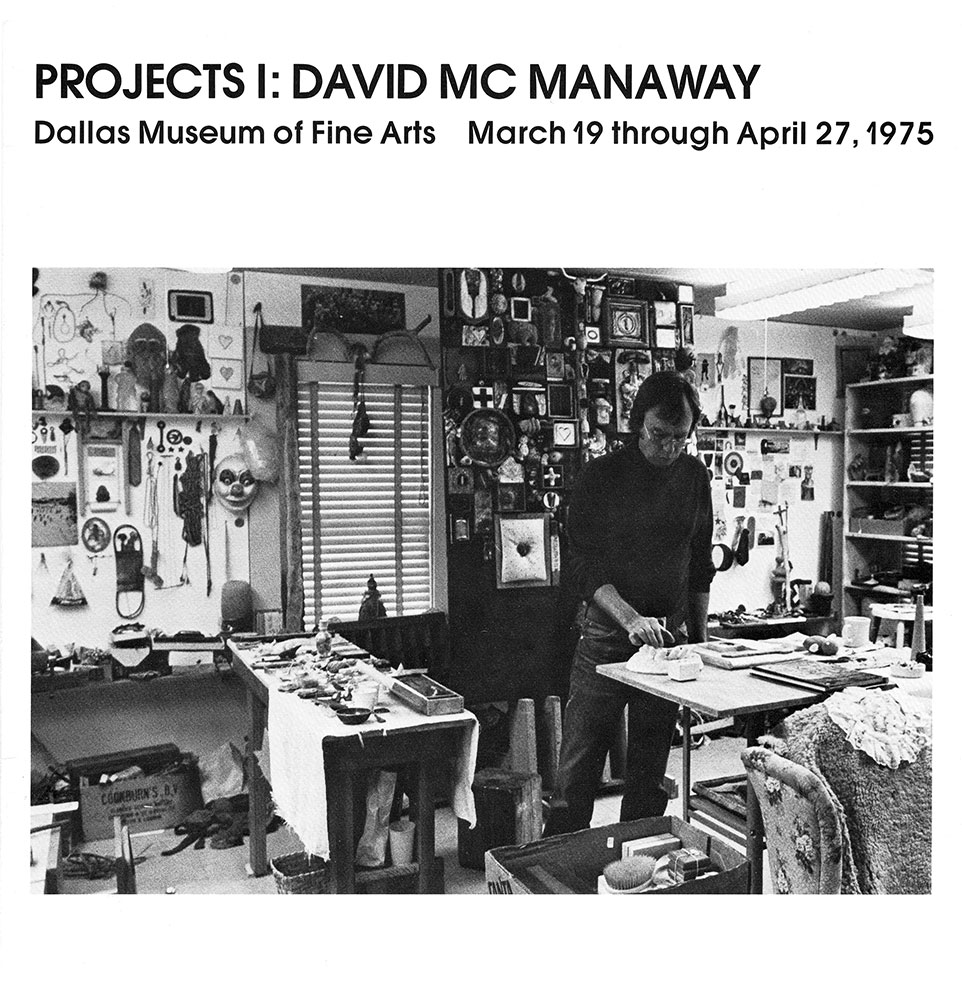

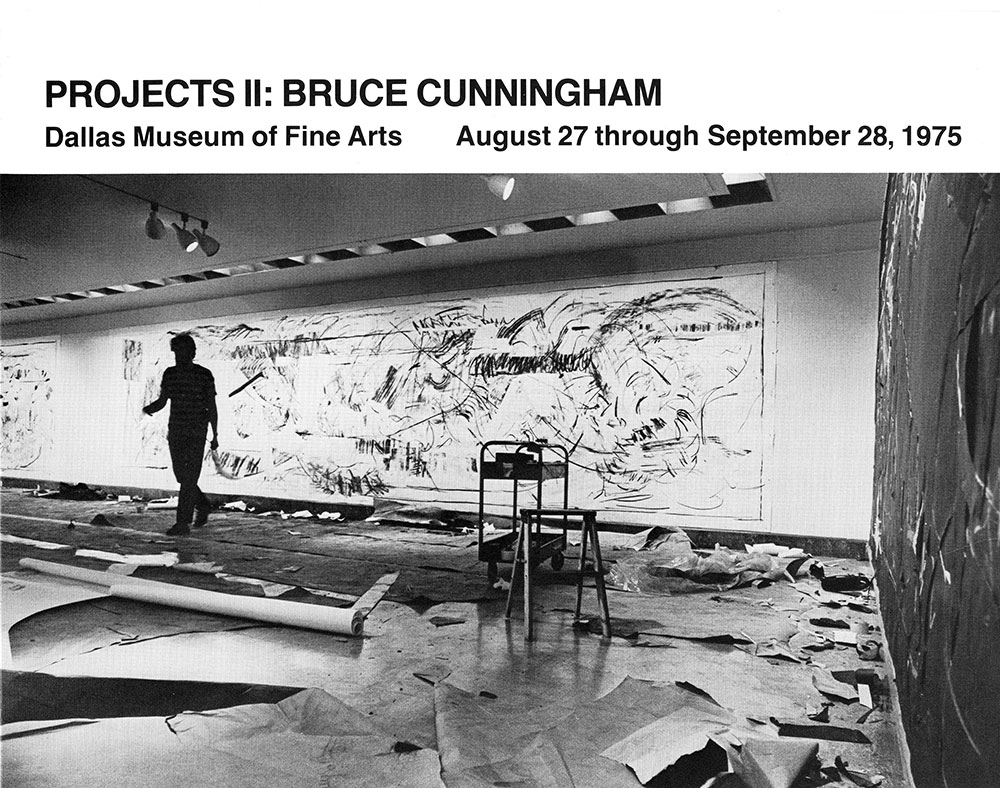

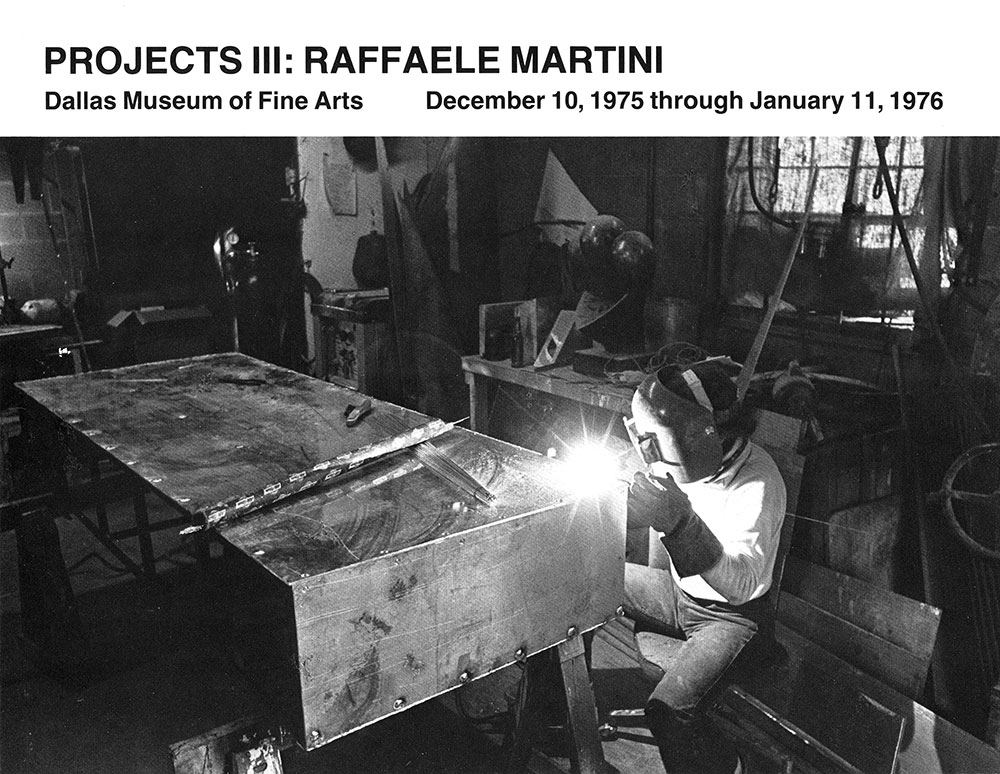

Following a run of major museum exhibitions like the Pablo Picasso exhibition of 1967 and retrospectives of Mark Tobey (1968), Franz Kline (1968), David Smith (1969), and Richard Tuttle (1971), Murdock inaugurated a series of small exhibitions titled Projects. The idea was to give an individual artist the opportunity to transfer his or her studio practice to the DMFA galleries. Whether or not Murdock intended it, the short-lived series featured three artists who lived and worked in Dallas: David McManaway, Bruce Cunningham, and Raffaele Martini (Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Fig. 21).

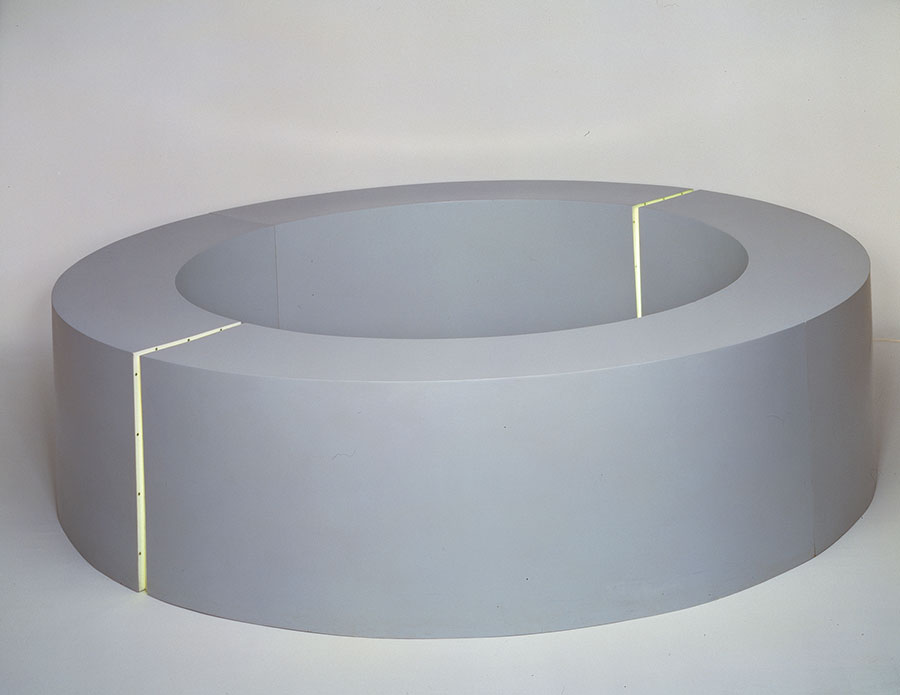

While curator of contemporary art, Murdock oversaw the acquisition of several major works of art, including Jasper Johns’ Device, 1961–1962 (Fig. 22), which was a gift to the Museum by the Art Museum League, Margaret J. and George V. Charlton, Mr. and Mrs. James B. Francis, Dr. and Mrs. Ralph Greenlee, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. James H. W. Jacks, Mr. and Mrs. Irvin L. Levy, Mrs. John W. O'Boyle, and Dr. Joanne Stroud in honor of Mrs. Eugene McDermott. Other important works acquired during Murdock’s tenure include: Jules Olitski, Mojo Working, 1966 (Fig. 23); Lucas Samaras, Transformation: Mixed, 1967 (Fig. 24); Larry Poons, Untitled #22, 1972 (Fig. 25); Robert Morris, Untitled, 1965–1966 (Fig. 26); and Tony Smith, Willy, designed 1962, fabricated 1978 (Fig. 27).

After Murdock’s departure in 1978, the Museum found itself without a curator of contemporary art for the next three years. Director Harry S. Parker III continued Rueppel’s transformation of the regional museum by expanding international collections and staging major exhibitions. In an attempt to continue some interaction with the local art scene, Parker organized 12: Artists Working in North Texas by appointing as curators three established local artists who developed a group exhibition surveying the work of regional artists. Jeanne Koch, David McManaway, and Mac Whitney selected artists they thought best represented the state of the arts in North Texas (Fig. 28, Fig. 29). This group show was the first and last of its kind.

In 1981, Parker appointed Sue Graze as curator of contemporary art. As one of her first orders of business, Graze developed the exhibition series Concentrations, which presented the work of emerging and midcareer contemporary artists in small, tightly conceived exhibitions that were intended to “present the depth and range of an individual’s work, thus serving as an index to recent developments in contemporary art.” The inaugural exhibition featured work by Fort Worth–based artist Richard Shaffer. The series has continued off and on at the Museum up to the present. As of 2012, there have been 55 Concentrations exhibitions by local, regional, and international artists.

Despite all the activity in and around Fair Park, the area was a relative ghost town during the off-season. As low-income housing developed to the south of the fairgrounds and the demimonde culture of nightclubs and tattoo parlors developed to the northwest in Deep Ellum, the neighborhood of South Dallas became increasingly crime-ridden. Access to the Museum was a chief concern for many patrons and board members, who typically lived in areas north of Fair Park or in the suburbs. Getting to and from the Museum meant traveling through neighborhoods that provoked unease, particularly after dark. Aside from a major retrospective of African-American art—Two Centuries of Black American Art—in 1977, the DMFA failed to provide programming or regular exhibitions of work by artists who represented the demographic of the Museum’s immediate audience in South Dallas, as Dallas Morning News columnist Janet Kutner noted:

Located as it is in the midst of a black area, DMFA has, it seems to me, a major responsibility to open its doors (with effort made to attract other than school tours) to the inhabitants of its immediate environs. Whether this requires shows of special interest or simply a better effort to draw the neighboring community in by specific invitations or programs until such visits become less rare and more frequent is a matter to be decided. What does seem certain, however, is the DMFA has a community at its doorstep with which it has essentially no relationship whatsoever. Quite a different situation from that here in Houston and elsewhere in the country where patrons as well as museums are taking art to the people rather than waiting for the people to come to it.

The DMFA had already expanded its Fair Park building once, during Merrill Rueppel’s directorship in 1965. Now the need for a larger facility was becoming more apparent, as both exhibitions and the permanent collection grew in size. Rather than expand the existing building, board members and DMFA administrators looked at options for a new building in a new, more accessible location. Using the slogan, “A Great City Deserves a Great Art Museum,” they campaigned to Dallas voters, who passed a $24.8 million bond issue in 1979 allowing the Museum to leave the increasingly undesirable Fair Park area for a new arts district being planned for the northeast corner of downtown. Today’s Dallas Arts District was born in 1984 with the opening of the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Dallas Symphony followed not long after.

The loss of a major cultural institution had a deep impact on the arts and culture in and around Fair Park and South Dallas. Artists who had lived and worked there relocated to other neighborhoods, and for some time, few commercial or alternative art spaces remained. Efforts to revive the area were unsuccessful until the South Dallas Cultural Center (SDCC) opened just outside Fair Park in 1986. Nearly two decades in the making and funded by a 1982 bond issue, the center was part of a city program to provide arts facilities for neighborhood and community organizations. Tapping into the audience that eluded the DMFA during its time in Fair Park, it gave African-American and other minority artists a venue for recognizing and nurturing local talent. Today the 34,000 square-foot, city-owned facility—expanded in 2007—boasts a 120-seat theater, a visual arts gallery, and studios for dance, music recording, and various visual art forms. Over the years, SDCC leaders have maintained the central mission to showcase the heritage of the African Diaspora and generate pride in the African-American experience.

When artist Vicki Meek became the center’s manager in 1997, she focused on improving its connection with the community. “A lot of people came and thought this was the parole office because the parole offices down the street didn’t look much different,” Meek recalls. “You know, cinderblock building, nothing to really distinguish it. And more importantly, the community didn’t have any real engagement in this building as far as the programming.” To help bridge the gap, Meek initiated programs like Late Night Jam, which featured local jazz musicians from midnight until 3 a.m., and a visual arts program aimed at young students from the community.

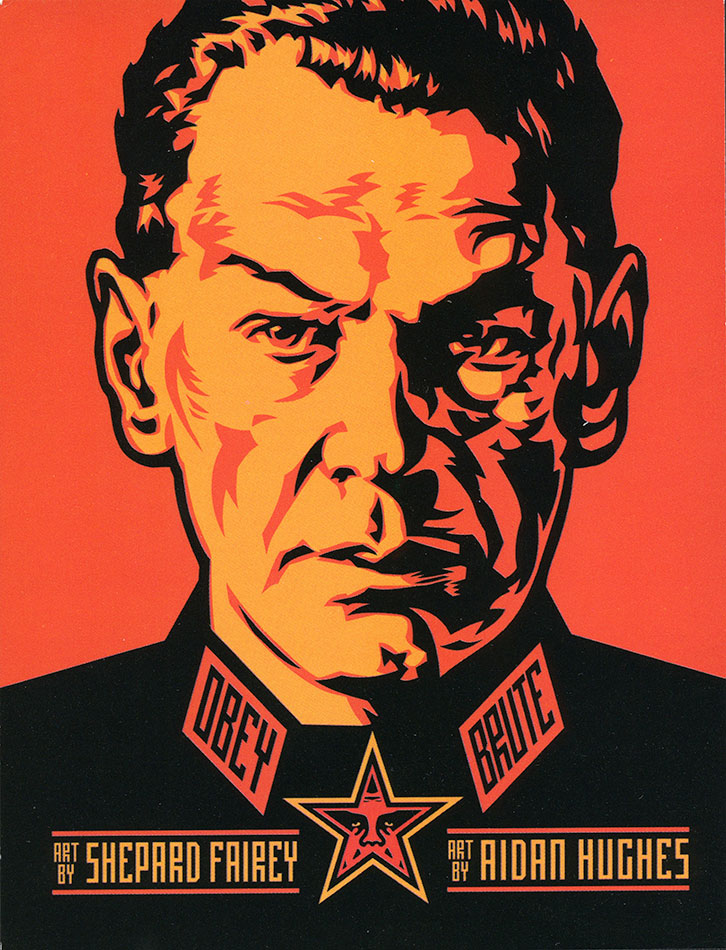

The South Dallas Cultural Center thrives as the hub of the Fair Park–South Dallas neighborhood in 2013. Over the years, several commercial galleries and alternative spaces have occupied the storefronts below the old 842 and Irwin Tuttie galleries. Spaces like Eugene Binder (1988–1993, Fig. 30); David Quadrini and Elliott Johnson’s Angstrom Gallery (established in 1996, Fig. 31); Dina Light and Steven Cochran’s gallery: untitled (established in 1997), and Jason Cohen’s Forbidden Gallery and Emporium (established in 2000, Fig. 32), kept the area fresh with activity into the 21st century. Just south of Dallas’ City Hall, Joe Allen’s Purple Orchid Gallery (2000–2002) and Randall Garrett’s Plush (established in 2000) occupied a warehouse on South Akard Street that also included artists’ working studios. Although they were separate ventures, both galleries were named Best New Gallery by the Dallas Observer in 2001, presumably due to their shared address.

In 2003, the Southside Artist Residency program introduced visiting artists to the neighborhood, and many of them kept studios there after their residencies had concluded. When the program was reintroduced as CentralTrak, the University of Texas at Dallas Artists Residency, it continued the spirit of the live-work studios and exhibition spaces that existed in the neighborhood some 30 years earlier. Through artist-run spaces and established anchors like the South Dallas Cultural Center and CentralTrak, the Fair Park–South Dallas neighborhood remains a vital part of the Dallas art macrocosm, sharing attention and activity with its neighbor, Deep Ellum.