The art world is an ever-expanding system of networks, connected through the relationships of those who are a part of it. Looking back 50 years, a fledgling art community was beginning to emerge in postwar Dallas. The city had less than half of today’s population and far fewer arts organizations, so the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (DMFA) was the nucleus of this community, the place to see contemporary art in the galleries and practice it in the Museum School. Until the 1960s and 1970s, when the gallery scene expanded and North Texas universities began establishing art departments, the DMFA was the leading source of support for educating and promoting contemporary artists. Through exhibitions of local artists and annual juried competitions like the Texas Annual Painting and Sculpture Exhibition and the Southwestern Exhibition of Prints and Drawings, the Museum supported area artists by showcasing their work and acquiring many of the prizewinning entries. The DMFA’s contemporary collecting had lacked focus until the 1950s, in part because it had no departmental curators. Direction came from a small group of board members who served on the Dallas Art Association’s acquisitions committee, guided by the Museum director.

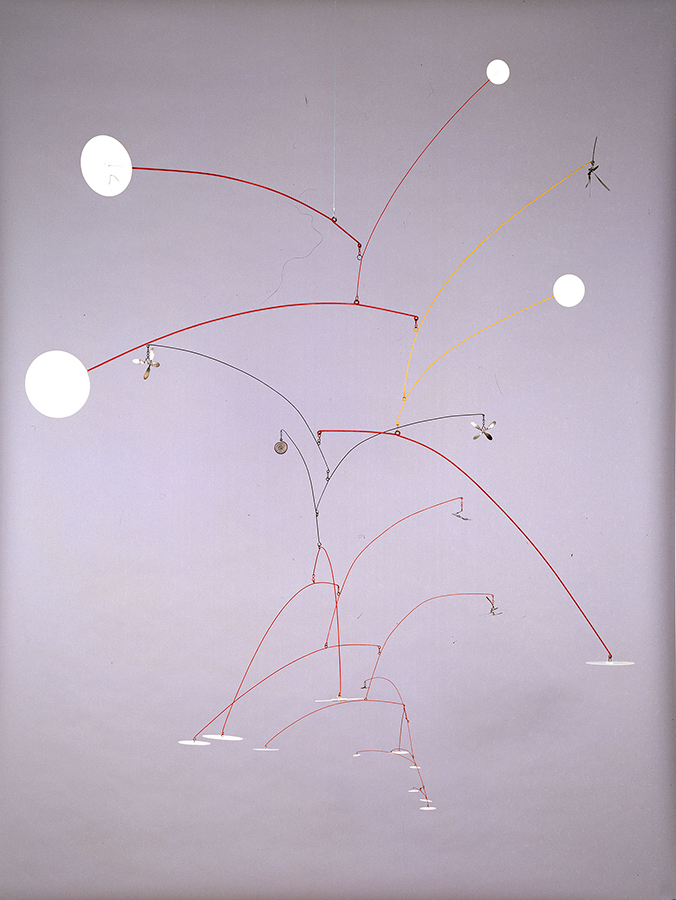

Jerry Bywaters was the first director to have a true vision for the future of the collections. During his tenure, from 1943 to 1964, Bywaters—a Texas artist—oversaw the acquisition of several important works of modern and contemporary American and Mexican art, including the Museum’s first piece of modern sculpture, Alexander Calder’s Flower, 1949 (Fig. 3), commissioned in honor of Mrs. Alex Camp and given to the Museum on behalf of the Dallas Garden Club. Bywaters continued to encourage collecting in contemporary American and Mexican art. As early as 1951, he developed an acquisitions plan that listed as the Museum’s priorities regional arts, 19th- and early 20th-century American art, contemporary American art, and contemporary Mexican art, suggesting an awareness of and appreciation for contemporary art despite his limited national and international contacts.

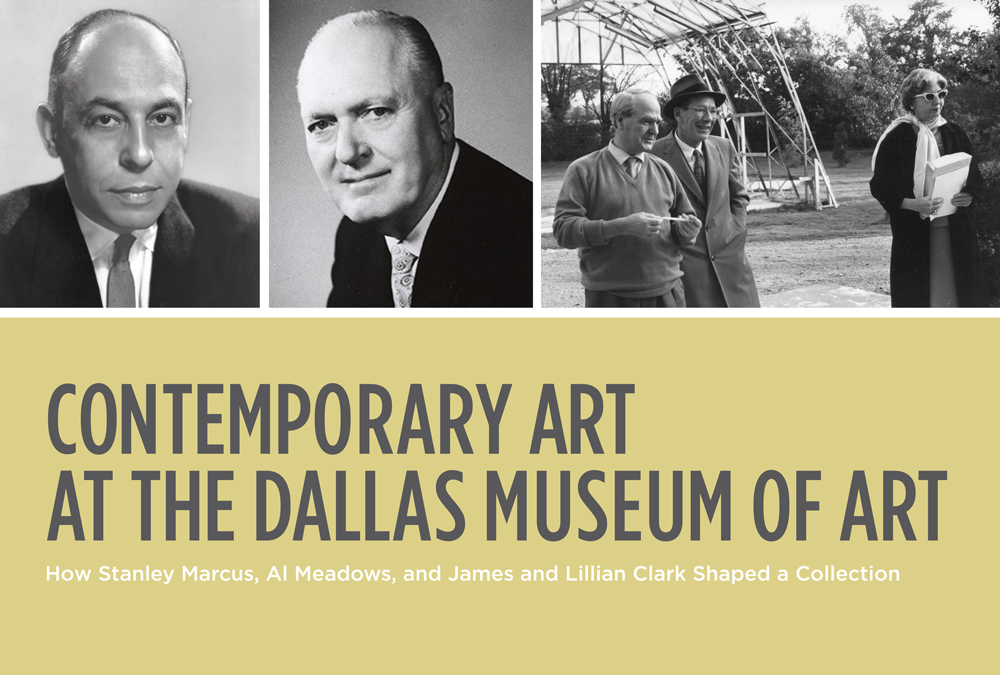

Civic pride led many of Dallas’ elite to contribute their time, money, and private collections of art to the Museum in the hope of developing the city into a true center for arts and culture. Through these leaders’ vision, the city slowly came around to accepting more challenging work, and the Museum acquired seminal masterpieces by major contemporary artists. Their efforts often met public resistance, especially in the 1950s. The resulting schism led to the creation of an independent contemporary museum, the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts (1956–1963). Though short-lived, it was an example of the passionate personalities behind the eventual development of the DMFA’s major contemporary collections. Four people in particular—Stanley Marcus, Algur H. Meadows, and James H. and Lillian Clark—supported the growth of contemporary collecting beginning in the 1950s and continuing through the 1960s and 1970s. All were members of the Dallas Art Association (the DMFA’s governing body), and all remained lifelong supporters of the Museum.

Stanley Marcus: The Beginning of Contemporary Art Collecting

After Calder’s Flower, the Museum’s next contemporary art acquisition—and possibly its most important—was a seminal work by Jackson Pollock, Cathedral, 1947 (Fig. 4). The painting was given to the Museum in 1950 by Mr. & Mrs. Bernard J. Reis, who had purchased it from Pollock’s dealer, the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York. Reis was a New York collector, former director of Marlborough Gallery, and until 1975 an executor of Mark Rothko's estate. In 1951 the Reises also gave to the Museum a collection of prints and works on paper by modern masters André Masson, Kurt Seligmann, André Breton, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, Marc Chagall, Alexander Calder, and Robert Motherwell, along with a Masson surrealist print portfolio.

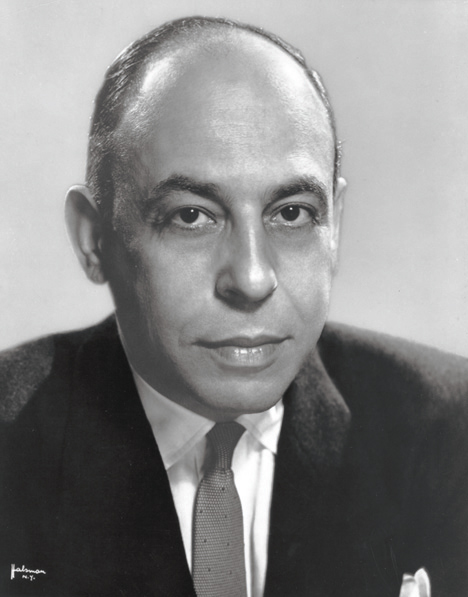

The gift of Pollock’s Cathedral can be credited in large part to Bernard Reis’ friendship with arts patron and civic leader Stanley Marcus (Fig. 5), president and later chairman of Neiman Marcus, who was a board member of the Dallas Art Association (DAA) at the time and would serve as vice president from 1951 to 1952. The story of the gift varies according to Marcus’ and Reis’ recollections. Marcus said that during a visit to New York, Reis mentioned to him in passing that he wanted to give away some works of art. Marcus, who headed the DAA acquisitions committee, seized the opportunity. He remembered saying to Reis: “How would you like to give one to our museum? It’s very hungry. It can’t get the money to buy one, but I’m sure that it would take it if given.” Reis suggested the Pollock in the hope of placing the young artist’s work in “a section of the country where there is no Pollack [sic] at the present time.” While Marcus was excited at the prospect of including such a progressive work in the DMFA’s collection, he worried that the board would not approve of the acquisition. “I’m afraid the audience won’t understand it,” he told Reis. Reis replied, “Don’t worry, their children will.”

Despite Marcus’ interest in contemporary art, the DAA board—with the rest of the city of Dallas—was unprepared to move into the contemporary collecting realm. The Museum focused on developing a stronger European collection, with most board members expressing interest in French art, the popular trend at the time. When Marcus encouraged the acquisitions committee to consider venturing into contemporary or even Mexican and South American art, he encountered resistance. Director Jerry Bywaters’ taste for contemporary art emphasized architecture, contemporary Mexican art, and the art of his fellow Texas regionalists, while the Museum supported Southwest regionalist painters through most of the 1940s and 1950s.

With the encouragement of Marcus and the acquisitions committee, in 1951 Bywaters was able acquire exemplary works by Mexico’s leading artists of the time from the Fred Davis collection, including Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Miguel Covarrubias, and Rufino Tamayo. The collection was purchased from Inés Amor’s Galeria de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City, the first gallery in the country devoted to contemporary Mexican art and one of the first to show the work of Tamayo, Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo, and modern Mexican artists. Betty McLean (Blake) also purchased work from the Galeria de Arte Mexicano for her own collection and used it as a source for art from the Mexican School that she exhibited in her gallery. Through Amor, Stanley Marcus met Tamayo, and their friendship led to the commissioning and acquisition of the artist’s monumental mural, El Hombre (Man), 1953 (Fig. 6).

The story of the El Hombre commission, like that of Pollock’s Cathedral, is legendary at the Dallas Museum of Art. Fraught with drama, it began with the artist’s friendship with Stanley Marcus and was almost derailed when the painting was lost for several weeks in an abandoned freight car outside Laredo, Texas. Marcus broached the subject of a mural during a visit with Tamayo and his wife, who were in the United States for a lecture Tamayo was giving in Amarillo, Texas. The couple were expected at Marcus’ Dallas home for dinner the evening after the lecture, and they turned up several hours late, disheveled and angered over a misunderstanding in Amarillo and professing distaste for Texas and its people. Marcus, ever the diplomat, not only managed to change Tamayo’s attitude, but also persuaded him to paint a mural for the DMFA. He described the conversation this way:

About 10:30, he [Tamayo] came in with his wife, looking very bedraggled. You could tell something had happened, and I said, “What’s the matter?” He said, “We had an accident in Amarillo. Somebody hit our car, and then jumped out and called us dirty Mexican tourists. They had no respect for us, and I’m not sure that I ever want to do anything in this country.” And I said, “Rufino, one of my reasons for being interested in Mexican painting is because I think it’s the key towards establishing warm and understanding relations between our two countries. . . . This would be a good time for you to paint that picture you’ve been promising, except we don’t have any money.”

Tamayo completed the mural, but weeks after its expected delivery date, it had not arrived. Bywaters received a telephone call from a man in Laredo, Texas, who reported, according to Marcus, that the painting had been found “in a freight car that had been shunted off on a track and lived there during the winter. And nobody ever paid any attention to it until spring came along.” In the end, the mural was delivered just in time to be installed for the opening of the 1953 State Fair of Texas. Along with works from the Fred Davis collection, it formed the bulk of the Museum’s holdings of art by Mexican modern masters and characterized contemporary art acquisitions in the early 1950s at the DMFA.

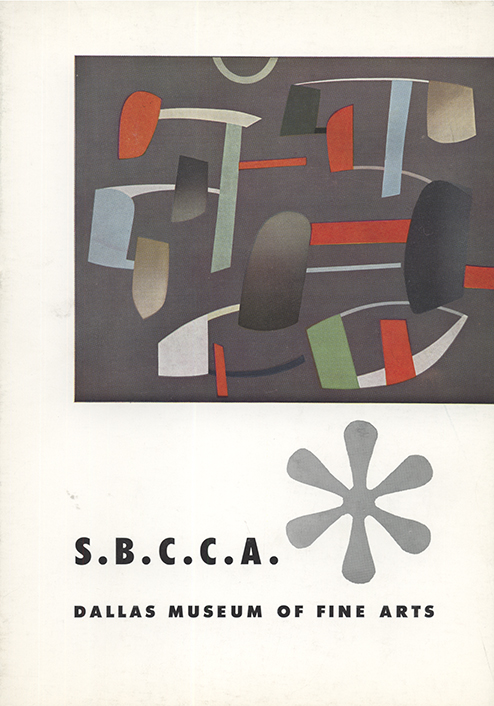

Stanley Marcus’ role was not limited to assistance with acquiring works of art. He also played a part in organizing exhibitions and supporting the Museum through several political controversies in the early 1950s. In 1952, Marcus organized Some Businessmen Collect Contemporary Art (SBCCA), an exhibition drawn from the collections of some of the nation’s most esteemed business leaders (Fig. 7). As vice president and chairman of the DAA acquisitions committee, Marcus felt a special responsibility to broaden the Museum’s audience. With SBCCA, he hoped to educate Dallas citizens about contemporary art.

At the time, McCarthy-era censorship was threatening the arts. Just a month before SBCCA opened, Representative George Dondero of Michigan delivered a famous speech to the US House of Representatives attacking modern art as “‘Communist’ because it bred ‘dissatisfaction’ by virtue of the fact that it was unintelligible to ordinary Americans whose ‘beautiful country’ it failed to ‘glorify.’” Many conservative citizens in Dallas shared Dondero’s sentiments, and extreme, anti–modern art rhetoric spread across the nation.

As a rebuttal, Marcus assembled works of art from some of the nation’s most esteemed business leaders. He hoped to show the public that there was no correlation between modern, contemporary, or abstract art and communism. Loans for the exhibition came from big names in American business, such as John de Menil, Albert D. Lasker, and Walter P. Paepcke. The exhibition was a success in terms of attendance and critical response, but it did nothing to educate Dallas about the distinctions between modern and contemporary art and communism.

Just a few years later, in 1955, the Museum faced the pressures of its conservative public when the Public Affairs Luncheon Club of Dallas issued the “Resolution on the Promotion of the Work of Communist Artists” on March 14, 1955, imploring the DAA Board of Trustees to cease acquiring and exhibiting work by artists with communist affiliations.” Marcus and director Jerry Bywaters maintained a united front against censorship, but the board undermined their stance when, in Marcus’ absence, it released a statement relinquishing any responsibility for showing or even knowing about communist-associated art. “It is not our policy knowingly to acquire or exhibit the work of a person known by us to be now a Communist or of Communist-front affiliation, or otherwise give aid or comfort to any Communist,” the statement read. Marcus later expressed his disagreement with trustees’ action because it “connected art and politics, and he felt that the museum would suffer from this action.”

Marcus again defended modern and contemporary art when he helped bring the traveling exhibition Sport in Art to the DMFA in 1956. Assembled by the American Federation of Arts for Sports Illustrated, the show was a collection of 102 sports-inspired paintings, prints, and drawings from American museums and was scheduled to travel to several venues before going on to the 1956 Summer Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia. Though Marcus was no longer a member of the DAA Board, the exhibition was cosponsored by the DMFA and his department store, Neiman Marcus. When early promotional material for the exhibition reached the Dallas audience, it drew the attention of the Dallas County Patriotic Council, which criticized the DMFA and Neiman Marcus for supporting communist or communist-sympathizer artists.

Marcus recalled in his autobiography Minding the Store that he received a phone call from a local business executive who informed him that the Dallas Patriotic Council had expressed great displeasure with certain paintings represented in this exhibition. The man advised Marcus to remove the paintings to avoid further controversy. Some of the undesirable works included Ben Shahn’s watercolor of a baseball game, Leon Kroll’s painting of a winter scene with sleighs, William Zorach’s depiction of an elderly man fishing, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s painting of a pair of skaters. The subjects of these works of art were not controversial, nor could they be linked to communism or communist sympathizers, but because of the suggestion of a communist connection, they were blacklisted by conservative Dallasites.

Rather than pull his support from the exhibition to avoid a scandal, Marcus remained steadfast and encouraged the DAA Board of Trustees to do the same. In response to the Dallas County Patriotic Council, the board reiterated its December 7, 1955, policy, a reversal of its April 4, 1955, statement on art and politics: “The policy of the trustees of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts is to exhibit and acquire works of art only on the basis of their merit as works of art; and to exercise their best judgment to protect the integrity of the Museum as a museum of art and as a municipal institution.” The exhibition was shown as planned, but the fractured board viewed this latest controversy as the last straw. Several members defected to form the Dallas Society for Contemporary Arts (later the DMCA), with Edward Marcus, Stanley’s brother, serving as its first president.

During his 60-year tenure as a trustee, Stanley Marcus was highly influential in building the Museum’s contemporary collections, and he also stood by the DMFA when his brother and other Dallas contemporary art supporters chose to establish the new museum in 1956. Though his personal collecting centered more on arts of the Americas, both ancient and modern, he was likely the driving force behind the Dallas Art Association’s efforts to keep up with the contemporary institution.

Al Meadows: A Contemporary Collecting Boom

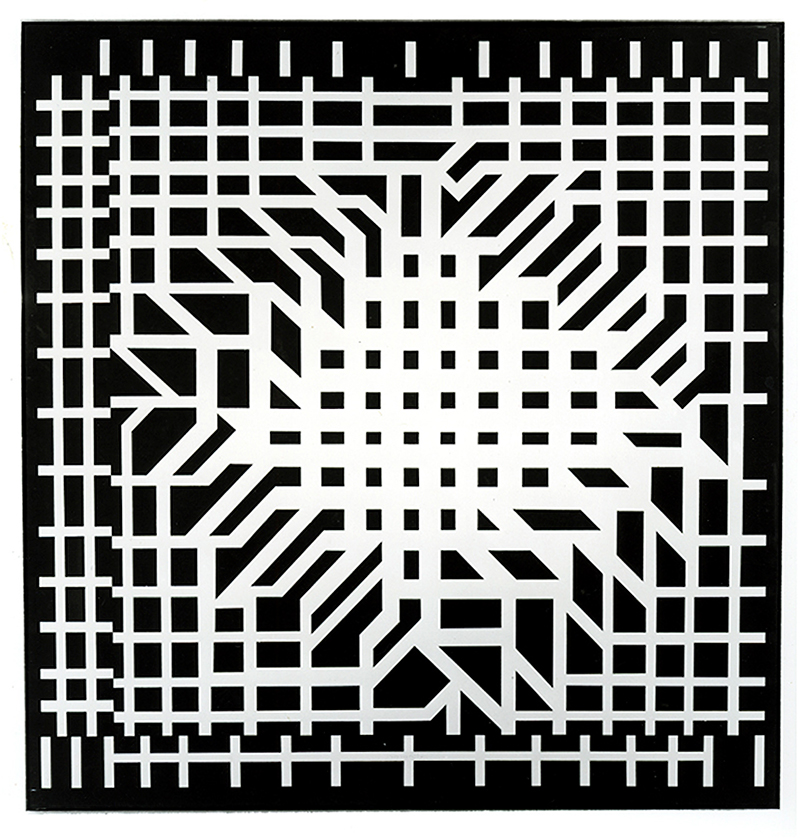

Collecting contemporary art at the DMFA waned until the appointment of Merrill Rueppel as director in 1964. Under the new director’s guidance, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts began collecting major contemporary works of art at an exciting pace. In 1965 the DAA made four major purchases: Henry Moore, Two Piece Reclining Figure, No. 3, 1961 (Fig. 8); Arshile Gorky, Untitled, 1943–1948 (Fig. 9); Victor Vasarely, Meride, 1961–1963 (Fig. 10); and Adolph Gottlieb, Orb, 1964 (Fig. 11). The new leadership must have been encouraging to local collectors, because before long, gifts of contemporary art began to fill in the collection.

One of Rueppel’s greatest achievements was the guidance he gave the Texas oilman Algur H. Meadows (Fig. 12) in forming a robust collection of exceptional works of contemporary art, which eventually came into the Museum’s permanent collections. Al Meadows was a major financial backer of the DMCA and would later develop, with Rueppel’s help, a significant postwar art collection. But he had a shaky start as an art collector and museum patron. A Texan who made his fortune in the oil and gas industry, Meadows’ interest in art collecting was piqued during a tour of the Prado Museum in Spain in the early 1950s. Encouraged at the thought of owning a collection of his own masterpieces, Meadows sought the help of art dealers who sold him what turned out to be the “largest private collection of fake paintings in the world.” All at once, Meadows acquired 10 paintings by “Spanish Old Masters,” followed by purchases of “El Grecos”and a few “Goyas.” Meadows continued to purchase art for his collection at a speedy rate, acquiring what he believed to be Spanish Old Masters during his first marriage to Virginia Garrison Meadows and moving into French impressionists to accord with the taste of his second wife, Elizabeth Boggs Bartholow, all the while relying on the same unscrupulous advisors who conned him into buying fake after fake for what they convinced him were bargain prices.

Local art dealer Donald Vogel got involved when he was approached as a member of the Art Dealers Association of America to evaluate the collection. Vogel invited Stefan Hahn and another associate from New York to help. When Vogel and Hahn determined that the vast majority were fakes, Meadows went to the DMFA for a second opinion from Rueppel, who backed the dealers’ evaluation. The scandal attracted national attention when Life magazine picked up the story.

Instead of giving up on collecting altogether, Meadows took action by firing his “advisors” and began purchasing an entirely new collection of Spanish Old Master paintings with the help of Spanish art expert, William B. Jordan, director of Meadows’ new museum at SMU, which opened in 1965. At Rueppel’s suggestion, Louis Goldenberg of Wildenstein & Company in New York advised him on French impressionist purchases. The results were extraordinary, as Meadows spared no expense in restoring his beloved collections—and his own reputation—to their rightful standard. As Rueppel recalled, at this point Meadows “began to buy really first-rate pictures.” The collection of Spanish paintings was promised to the Meadows Museum. He and his wife Elizabeth lived with the French impressionist works in their home, while most of them went to the DMFA in 1981. And he sought out contemporary works for the specific purpose of donating them to the DMFA.

The years of Meadows’ buying spree aligned with his time as a trustee of both the DMCA and the DMFA. During merger talks between the two institutions in 1962 and 1963, Meadows appealed to DMCA board members to move the museum to Southern Methodist University for relief from the costly mortgage payments on its current location, the Slick Airways Building (for which he was primarily footing the bill). The board never took this option seriously, but the DMCA did play a role in developing Meadows’ idea of an on-campus art museum for the private university of which he was also a trustee.

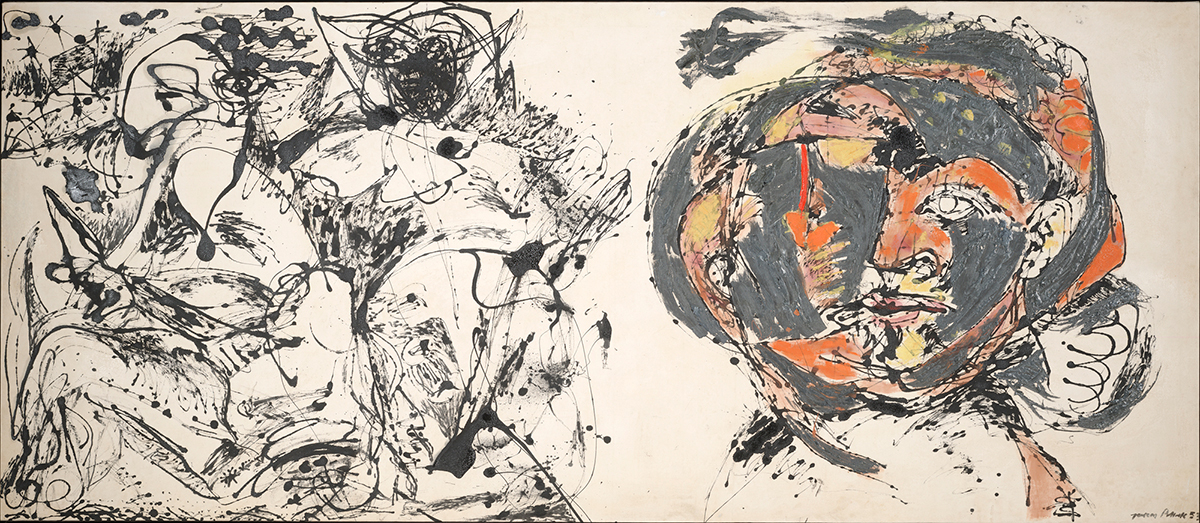

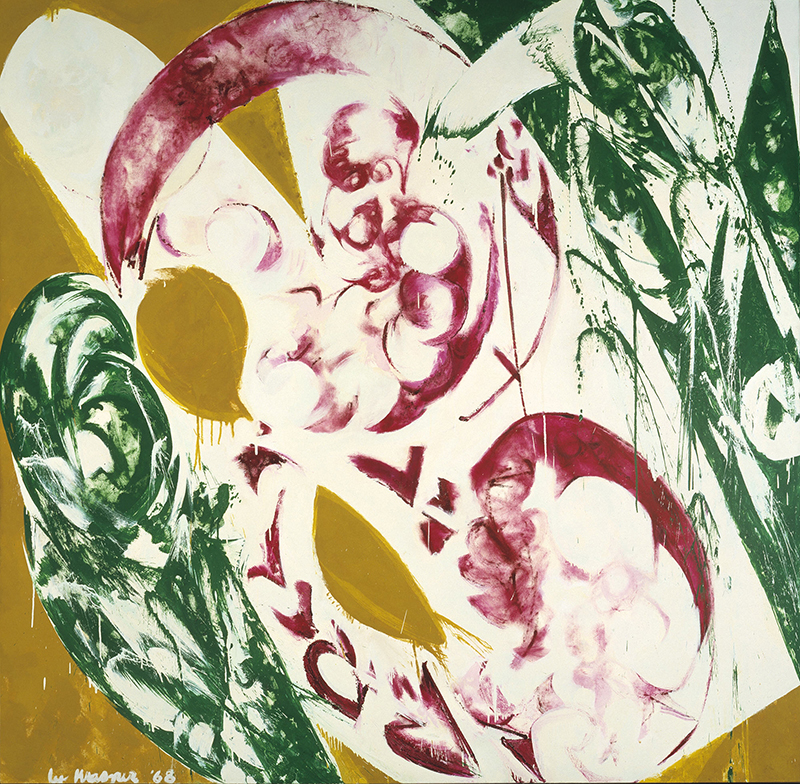

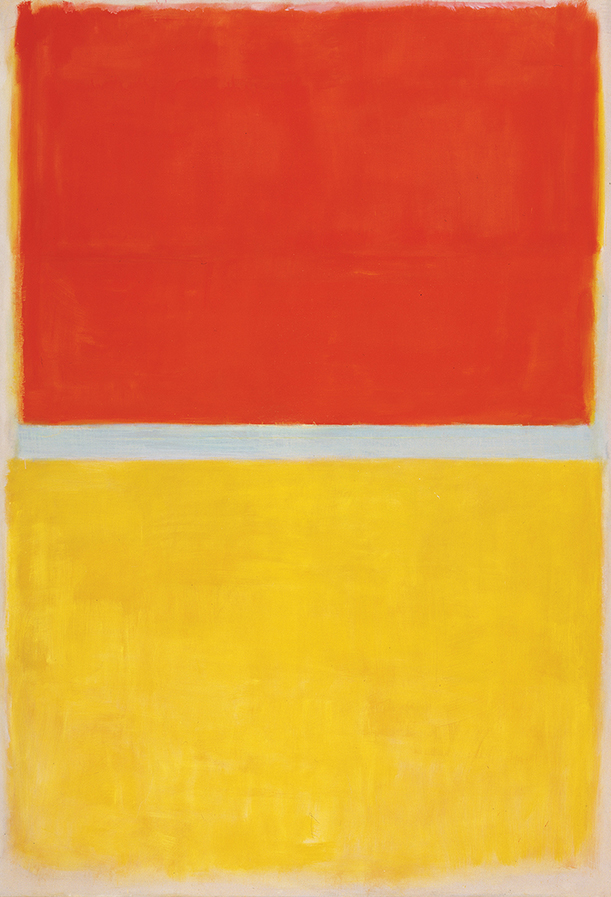

Of Meadows’ gifts to the DMFA during his lifetime, 11 were made during the Museum’s growth years under Rueppel’s directorship. Referred to by Meadows’ nephew, Curtis Meadows, as his “third collection,” these contemporary works include significant examples of abstract expressionism—Jackson Pollock, Portrait and a Dream, 1953 (Fig. 13); Mark Rothko, Orange, Red and Red, 1962 (Fig. 14); Lee Krasner, Pollination, 1968 (Fig. 15); and Franz Kline, Slate Cross, 1961 (Fig. 16)—as well as color field painter Morris Louis’ Broad Turning, 1958 (Fig. 17).

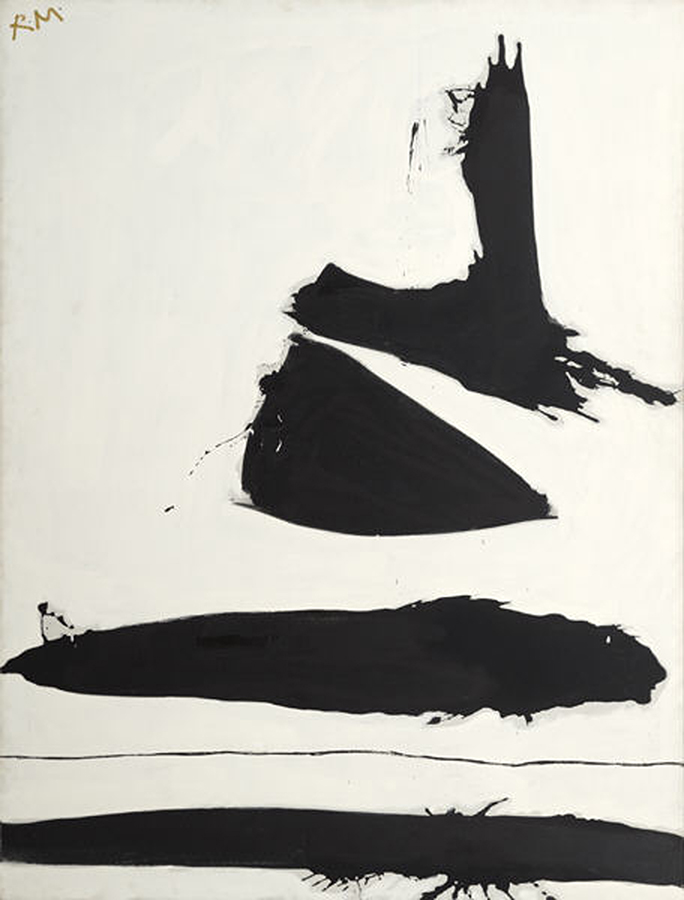

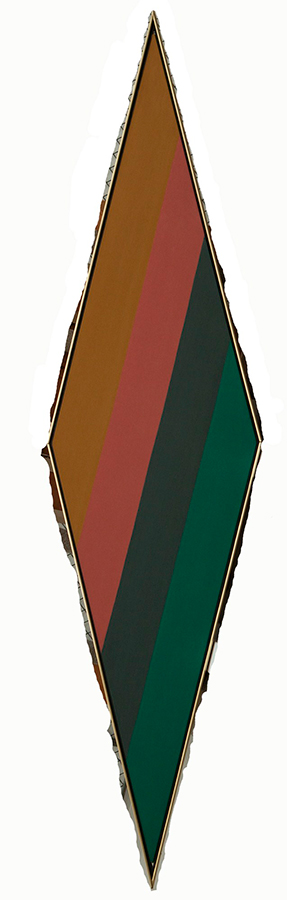

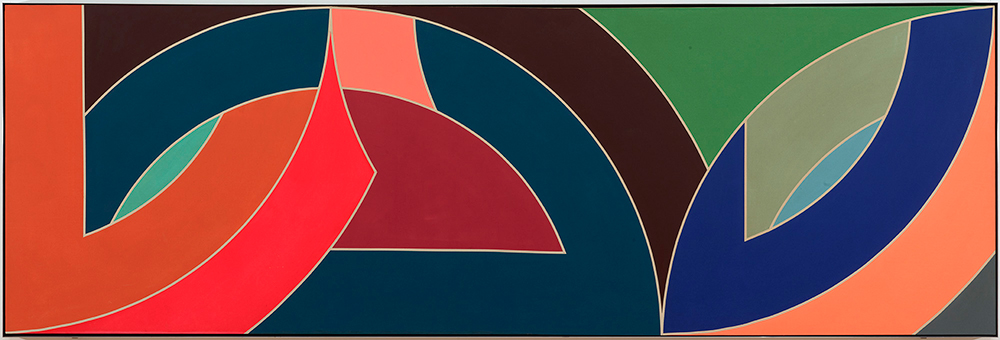

Meadows also played a major role in securing the gift of the Saenz collection of pre-Columbian art, and in his lifetime gave the Museum 90 objects of contemporary, European, African, and pre-Columbian art. The Meadows Foundation, Inc., an offshoot of Meadows’ business, made a substantial gift of primarily French impressionist paintings and many contemporary paintings in 1981 after his death in 1978. The contemporary works included James Brooks, Quand, 1969 (Fig. 18) and Ipswich, 1967 (Fig. 19); Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park No. 29, 1970 (Fig. 20); Robert Motherwell, In Black and White, No. 1, 1966 (Fig. 21); Kenneth Noland, Shade, 1967 (Fig. 22); Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1952 (Fig. 23); Frank Stella, York Factory Sketch, No. 1, 1970 (Fig. 24); and Clyfford Still, Untitled, 1964 (Fig. 25).

Al Meadows left a legacy as a major player in the Museum’s emergence from its 1950s reputation as a regional museum to that of a world-class institution with holdings in certain areas that rivaled those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As director emeritus Harry S. Parker III noted, “Meadows had been giving these amazing paintings. . . . When you think again of what he gave during that period—I mean, there were half a dozen really great things, and the whole center court of Dallas didn’t look too bad, . . . . [In] that area, it was better than the Met.” Meadows’ contributions to the city of Dallas extended to Southern Methodist University, where he endowed the Virginia Meadows Museum and donated his entire collection of Spanish Old Masters. He also created the Elizabeth Meadows Sculpture Court and Garden in honor of his second wife, Elizabeth Boggs Bartholow. Both the museum and the sculpture garden opened and were dedicated on the same day, April 3, 1965. In addition, Meadows gave the university a group of 41 sculptures by contemporary Italian artists, which were assembled in an exhibition by Galleria Odyssia in Rome and exhibited at the DMCA in 1960.

James H. and Lillian Clark: Carrying the Contemporary Collection Forward

James and Lillian Clark (Fig. 26) began collecting art rather late in their lives. They met in 1935 in New York City, where Lillian was a secretary at Johnson & Johnson and James was a securities analyst for Laurence M. Marks and Co. After living for several years in New York and California, a job as a financial advisor and senior associate with the Murchison family brought the Clarks to Texas in 1950. By 1958 the job proved too stressful, and Jim retired. On doctor’s orders for Jim’s health, he and Lillian took a trip to Europe, an experience that both credited as the beginning of their lifelong love affair (Lillian once called it an obsession) with building a collection.

The Clarks began by focusing on 19th-century French paintings and then ventured into collecting works by post-impressionist and School of Paris artists. In the 1960s, two events encouraged the Clarks to venture into the contemporary realm: they became involved with the DMCA, and they met the New York gallerist and collector Sidney Janis. As Jim Clark told a reporter, “First I collected Oriental art, then the Impressionists, now my basic interest is the art of the 20th century, specifically the ‘classic’ part of the 20th century: Mondrian, Picasso, Pollock, Tobey.” He expressed his belief that the DMFA “should follow a course which will lead to the building of a collection of the art of our times to stay abreast of the current trends, while at the same time working through special funds and gifts to acquire the art of the past times so that Dallas will truly have a museum of fine arts.”

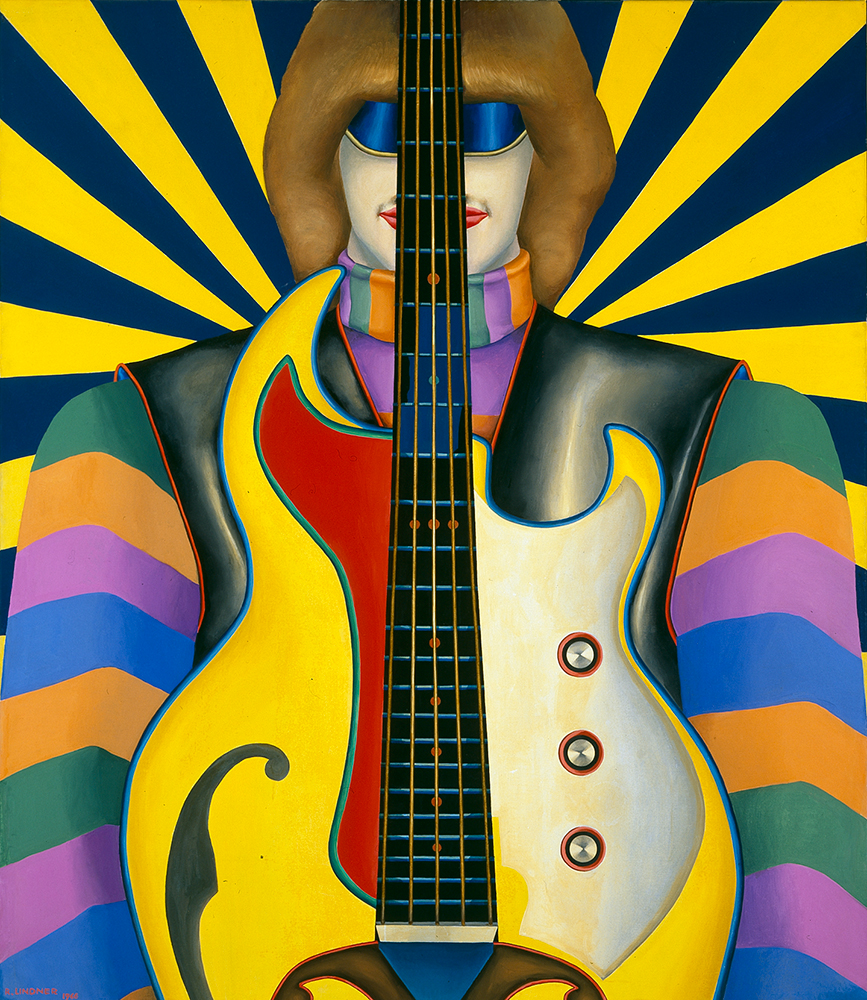

This attitude reflects the Clarks’ own collection and the works of art they gave to the DMFA and Foundation for the Arts: important modernist paintings, ancient Greek sculpture, a pair of Etruscan earrings, and a seated Buddha figure purchased during their 1958 trip abroad. The Clarks’ earliest gifts were for the contemporary collection, with most thoughtfully chosen and given to commemorate specific accomplishments or events for the DMFA. Early gifts included Barbara Hepworth, Sea Form (Atlantic), 1964; Jean Dubuffet, The Reveler (Le Festoyeur), 1964; and Richard Lindner, Rock-Rock, 1966 (Fig. 27), presented by James Clark when he retired as DMFA board president in 1968.

The Clarks continued giving throughout their lives, and their gifts included important contemporary paintings during the 1970s: Mark Tobey, Calligraphy in White, 1957, and Magic Woods, 1960; Barbara Hepworth, Contrapuntal Forms (Mycenae), 1965 (Fig. 28); Jean Dubuffet, Julie la Sérieuse, 1950, and Villas et Jardins, 1957; Jean Arp, Star in a Dream (Astre en Rêve), 1958; Victor Vasarely, Paraj, 1965; Bridget Riley, Rise 2, 1970; and Constantin Brancusi, Beginning of the World, c. 1920 (Fig. 29).

The Brancusi sculpture carries a famous story. At the time of the gift, the city had just failed to pass a bond issue that would have provided funds to move the DMFA out of its Fair Park location into the new downtown Arts District. Morale at the Museum was at a particular low, so in an effort to boost spirits and send a message to the city of Dallas, Jim Clark wrapped the sculpture in a towel, packed it in a Pan Am flight bag, took it to the Museum, and presented it on the spot to director Harry Parker and hastily assembled staff. This gesture not only bolstered the staff’s mood, but within a year, a $24.8 million bond issue succeeded, and planning began for the move to the Museum’s present location.

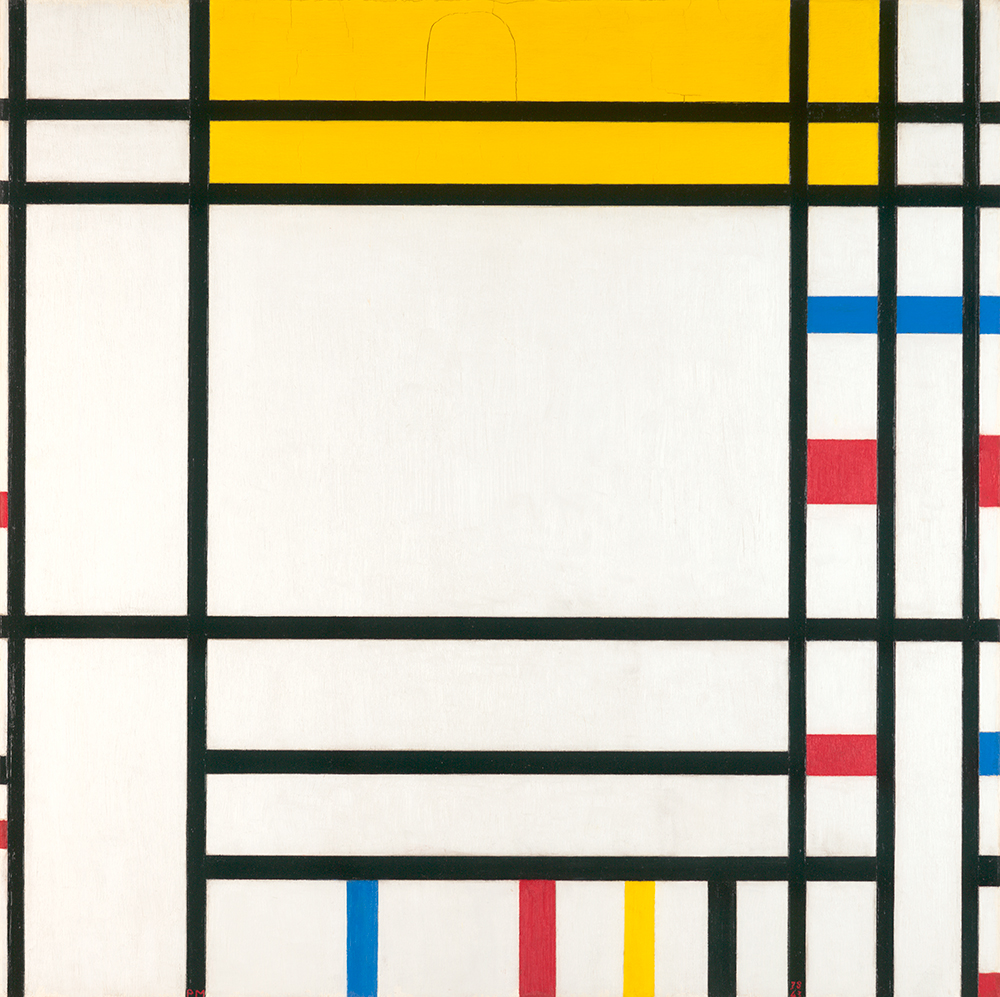

After Jim Clark’s death in 1979, Lillian remained a major donor following the wishes of her husband, who hoped their entire collection might become part of the Museum. Between 1981 and 1991, she gave the Foundation for the Arts a pair of paintings by Joseph Albers, a portfolio of El Lissitzky framed lithographs, and a Piet Mondrian painting, to accompany a gift from the James and Lillian Clark Foundation of five Mondrians (for example, Fig. 30) and three important Légers.

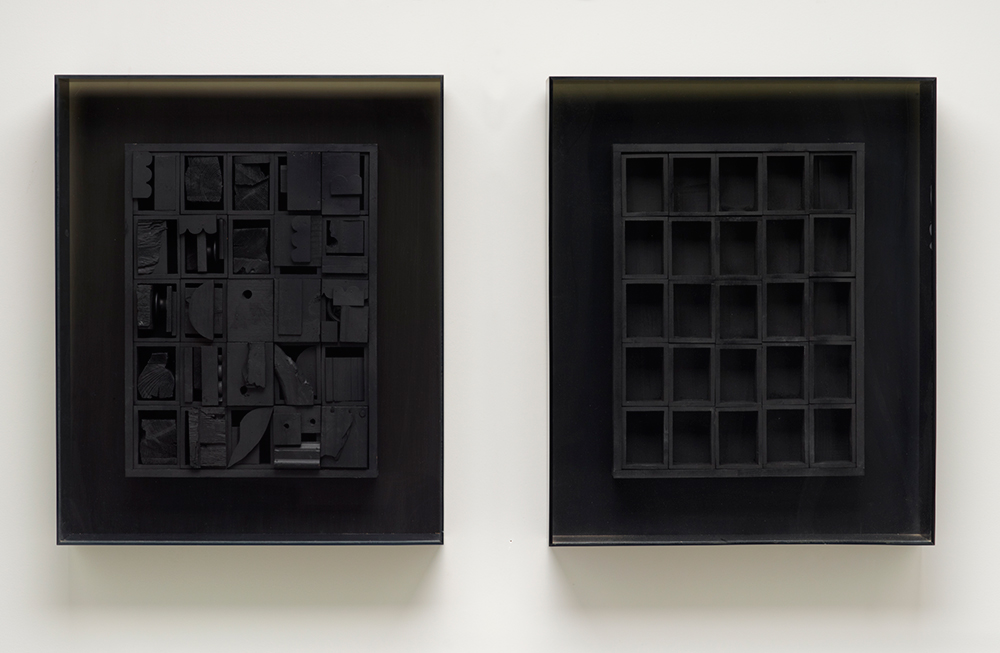

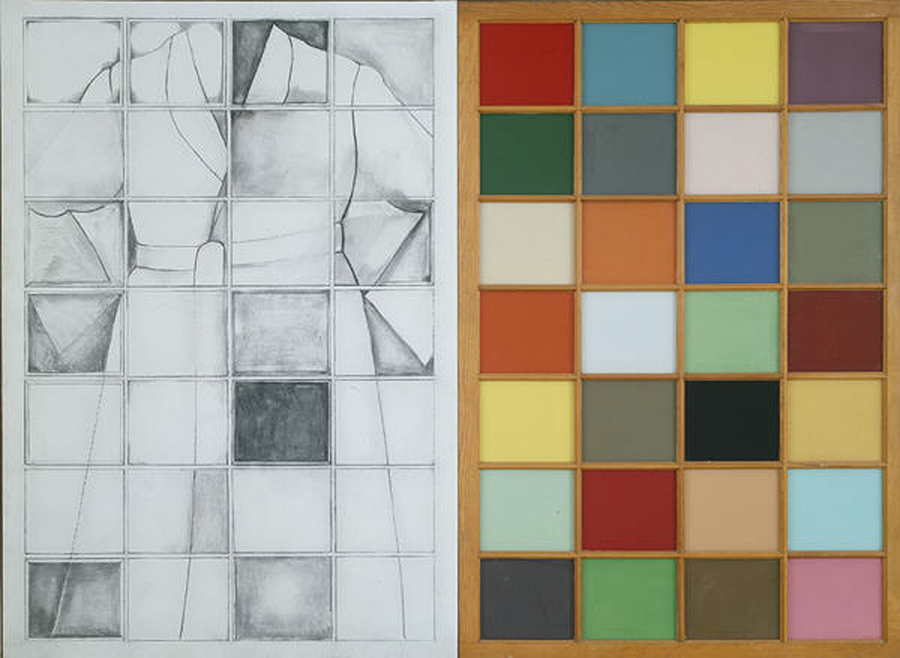

Through the efforts and generosity of Stanley Marcus, Al Meadows, and James and Lillian Clark, the DMA celebrates a robust and significant collection of contemporary art. These important donors and benefactors set a precedent for expanded collecting in a variety of media, including photography, video, sound, new media, and installation pieces. Works like Chris Burden’s All the Submarines of the United States of America, 1987, Bruce Nauman’s Perfect Door/Perfect Odor/Perfect Rodo, 1972, and Jenny Holzer’s I Am A Man, 1987, are all examples of the challenging works the DMA supports through its collections. The 2005 bequests of the private collections and future acquisitions of three major local contemporary art collectors—Marguerite and Robert Hoffman, Cindy and Howard Rachofsky, and Deedie and Rusty Rose—sets yet another precedent. Believed to be the first of their kind, these bequests are a 21st-century example of the type of cultural leadership in Dallas that began in the 1950s. These collectors’ generosity has transformed the Museum’s contemporary holdings into a living collection that can shift and adapt to swiftly changing patterns and innovations in contemporary art.