Just east of Downtown, Deep Ellum is defined by Elm Street, Canton Street, and Good-Latimer Expressway. This lively neighborhood was once known as the seedy underbelly of Dallas where brothels, jazz clubs, pawn shops, and fight-a-night bars operated side by side. In its early heyday in the 1920s and 1930s, Deep Ellum was the place to hear some of Texas’ best-known jazz and blues musicians, including “Blind” Lemon Jefferson, Sam “Lightnin’” Hopkins, and Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter. In the 1950s and 1960s, the neighborhood deteriorated, as Dallas’ population shifted to the emerging north suburbs. Until the 1970s, arts activity had been relegated mostly to the polished Uptown neighborhood and the nearby area of Fair Park–South Dallas.

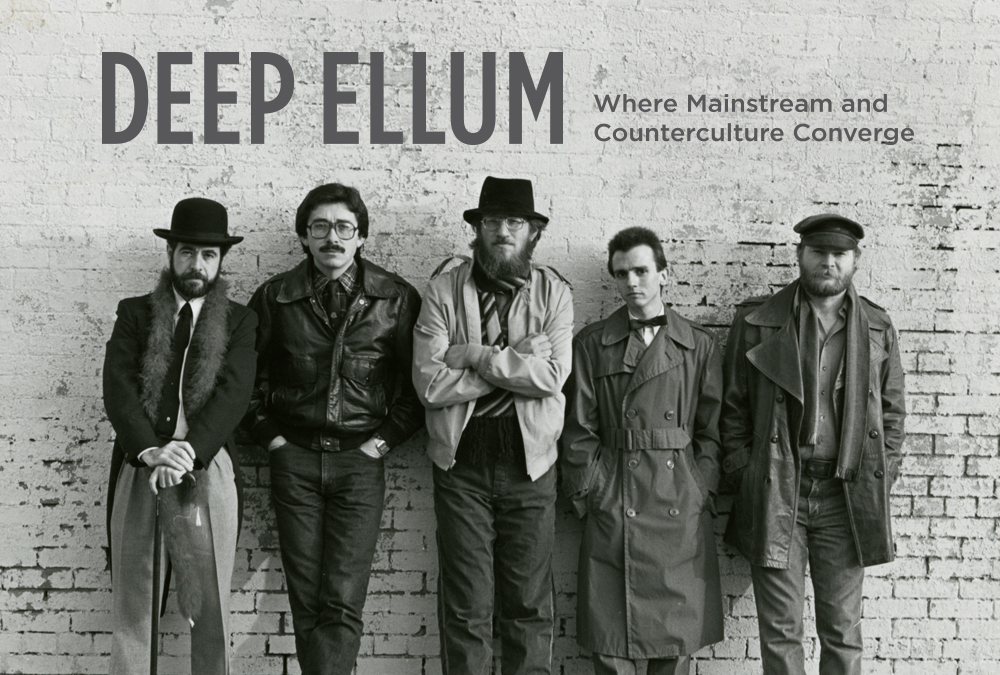

The first galleries to set up shop in Deep Ellum battled its reputation as a high-crime part of town. Gunfire and police sirens made up the neighborhood soundtrack, and it was difficult to get collectors to come there after dark. But the music scene—always a signature of Deep Ellum—made a comeback in the mid-1980s with the arrival of punk rock and New Wave. That decade was a moment when the arts and music scenes coalesced, making the neighborhood the hottest spot for both mainstream and counterculture.

The 1970s and 500X

Artists began moving into Deep Ellum in the 1970s for the same reasons they gravitated to other parts of Dallas: abundant open space and cheap rent in abandoned factories and warehouses. They converted buildings into livable spaces that doubled as studios and sidestepped traditional commercial galleries by staging their own exhibitions to gain exposure. This kind of do-it-yourself attitude led to the creation of several alternative and artist-run spaces, with 500 Exposition Gallery (now 500X) leading the way.

The oldest gallery in Deep Ellum and the oldest artist-run space in Texas, 500X was a catalyst for activity in the neighborhood. It opened in 1978 as 500 Exposition Gallery in an old tire warehouse on the edge of Deep Ellum that artists Richard Childers and Will Hipps purchased in 1976. Childers had been living in another warehouse space in Fair Park on the second floor of 842 First Avenue, where he and artist Gilda Pervin organized First Saturdays. At these monthly events, artists paid a nominal fee for space to display and sell their work directly to the public. Hipps was a recent transplant, fresh off a fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and recruited in 1975 to start the art department at the University of Texas at Dallas. During his tenure he created the bachelor of fine arts and master of fine arts programs and built the campus’ iconic Art Barn building.

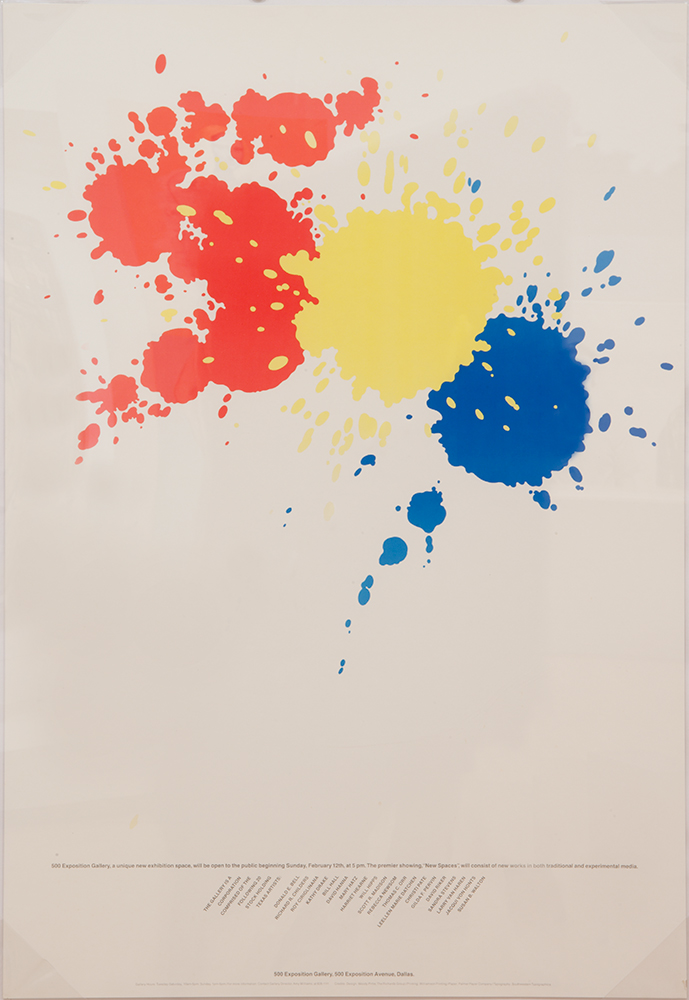

Taking ownership of the warehouse turned out to be the easiest aspect of establishing 500 Exposition Gallery. The space needed extensive renovation to realize Childers’ and Hipps’ dream of cooperative studios and gallery space. They recruited friends and fellow artists Scott Madison, Becky Newsom, Susan Walton, Gilda Pervin, and Christi Pate to help convert the building (Fig. 1). By 1978, 20 local artist-investors were considered equal owners of the space. Sixty percent of any sale went to the artist, while the remaining 40 percent went to the corporation. Funding was available to hire a director, so the artists invited Amy Williams Monier, a recent Wellesley College graduate, to head the gallery in its first year. The inaugural exhibition, New Spaces: Gallery Premier Group Show, presented work from the co-op’s 20 incorporated artists (Fig. 2). Later shows tended to focus on work by individuals or groups. Annual juried invitational exhibitions called Expo, displayed in one or all of 500X’s three galleries, began in 1992 and continue today. Judges have included Diana Block, director of the University of North Texas Art Gallery; Joan Davidow, director of the Arlington Museum of Art; Annegreth Nill, associate curator of contemporary art at the Dallas Museum of Art; Jeffrey Moore, director of Blue Star Art Space, San Antonio; Don Bacigalupi, curator at the San Antonio Museum of Art; Suzanne Weaver, assistant curator of contemporary art at the DMA; and Edmund P. Pillsbury, director of the Kimbell Art Museum.

500X has always been an alternative, experimental space for emerging artists seeking to make a name for themselves while avoiding the sales-driven gallery scene. In the beginning, it was also a response to artists’ dissatisfaction with area museums and their reluctance to show emerging artists. The gallery developed a reputation for doing things the way that artists wanted to do them. It offered a springboard to careers in Dallas’ major contemporary art scene, as well as a way to gain national and international visibility.

Artist and former member Celia Eberle remembers how 500X gave her the confidence to pursue a full-time career as an artist:

I found out about 500X from a seminar. . . . So I applied and they accepted me, and I was . . . delighted. I couldn’t believe that I was actually accepted by all these Dallas artists, and all of these . . . recent MFA grads, too, and that was . . . probably the most exciting thing that ever happened [to me] ultimately because I can’t remember being so excited ever in terms of art. . . . When I first joined 500X, I felt like I had found my long-lost tribe, I really did. It was . . . a great revelation for me personally, and it made me feel more confident about myself . . . to continue to explore the ideas that I already have.

Over the years, 500X has been a gathering place for artists working in all media. It hosted performance art with early works by Pam Burnley-Schol (The Weaving, 1980) and Kenneth Havis (Death of the Machine, Rebirth of the Spirit, 1980), as well as the performance art series curated by Courtney Brown, Object: A Series of Seven Performances (2012). Video and new media art, like Ron Lowe’s exhibition Sound Art (1980) and member Keitha Lowrance’s Curtain (2001), and installation art, like Randall Garrett’s Transmissions (1995) and Rebecca Carter and Thomas Feulmer’s collaborative installation on view in the Project Space during Under New Management (2008), have all been an important part of the artist’s experience at 500X. Between exhibitions, the gallery also hosted symposiums and panel discussions on topics ranging from women’s place in the arts to the developing local art scene.

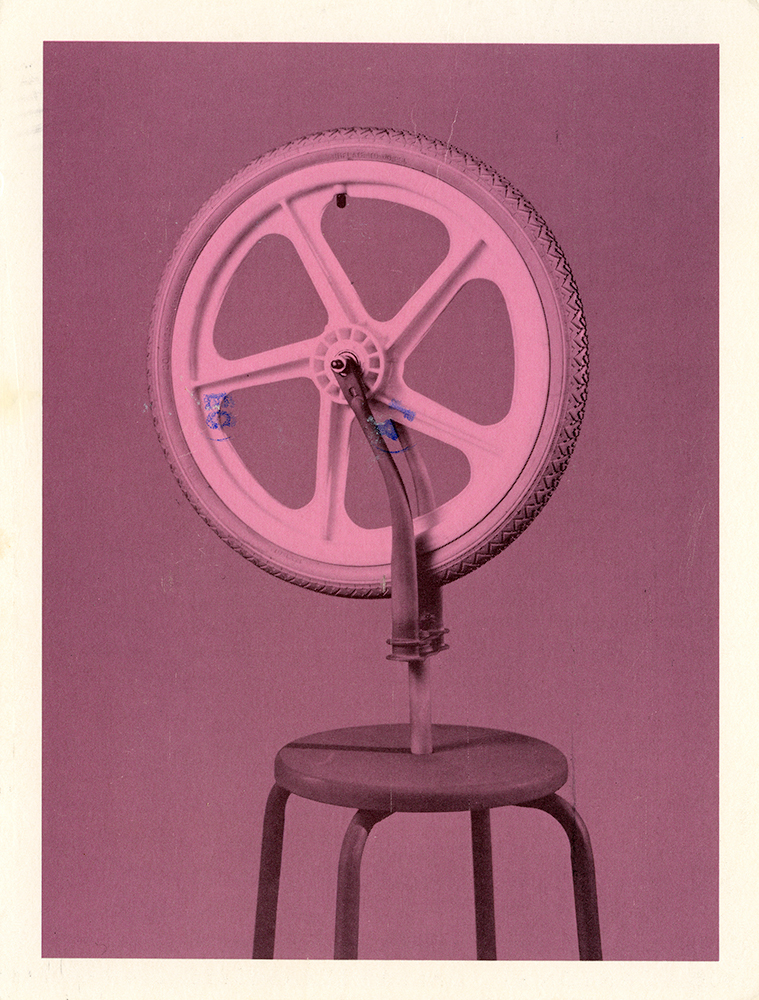

One notable early exhibition, Left/Right: The Political Show, was organized on the occasion of the 1984 Republican National Convention (Fig. 3). Curated by 500X member Dwayne Carter, this group exhibition responded to the current political climate with work by JR Compton, David Didear, Bert L. Long Jr., Bill McLean, Greg Metz, Barbara Simcoe, and Toxic Shock and a performance by Victor Dada. The show was wildly popular—especially Metz’s piece in the main gallery, Reagan’s Temple of Doom, which was equal parts three-dimensional political cartoon and garish carnival ride entrance (Fig. 4). The installation earned Metz national attention: kudos from the art crowd and death threats and vandalism to his studio from others.

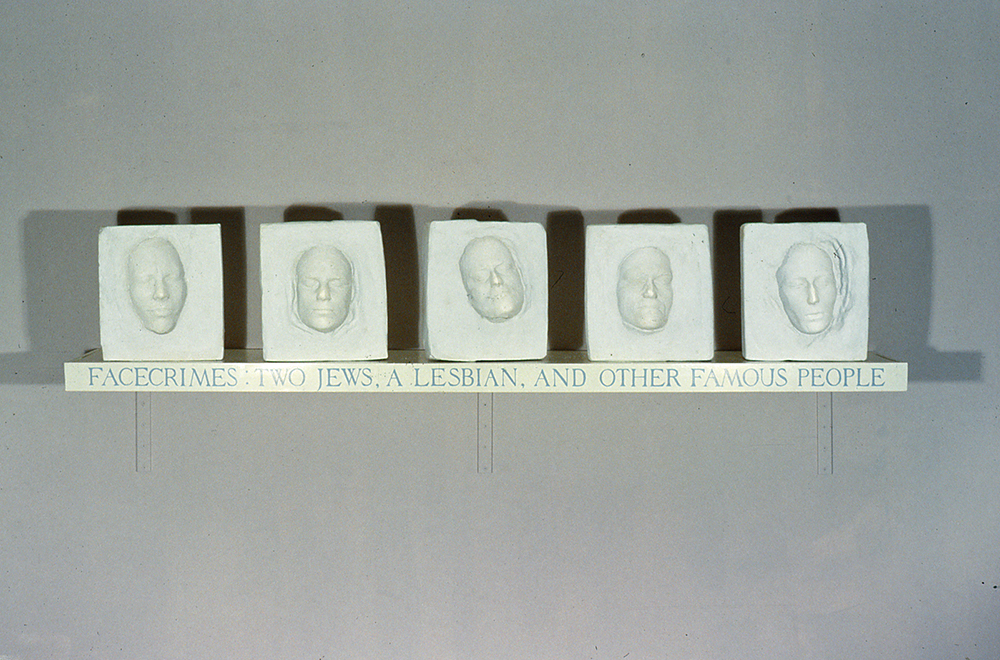

The all-female collective Toxic Shock (Frances Bagley, Julie Cohn, Linda Finnell, Debora Hunter, and Susan Magilow) included the sculptural piece Facecrimes: Two Jews, A Lesbian, and Other Famous People (Fig. 5). The work—an arrangement of plaster-cast self-portraits mounted on a wooden shelf with the title as an inscription—alludes to George Orwell's novel 1984 and also to a derogatory comment about diversity by former Secretary of the Interior James Watt.

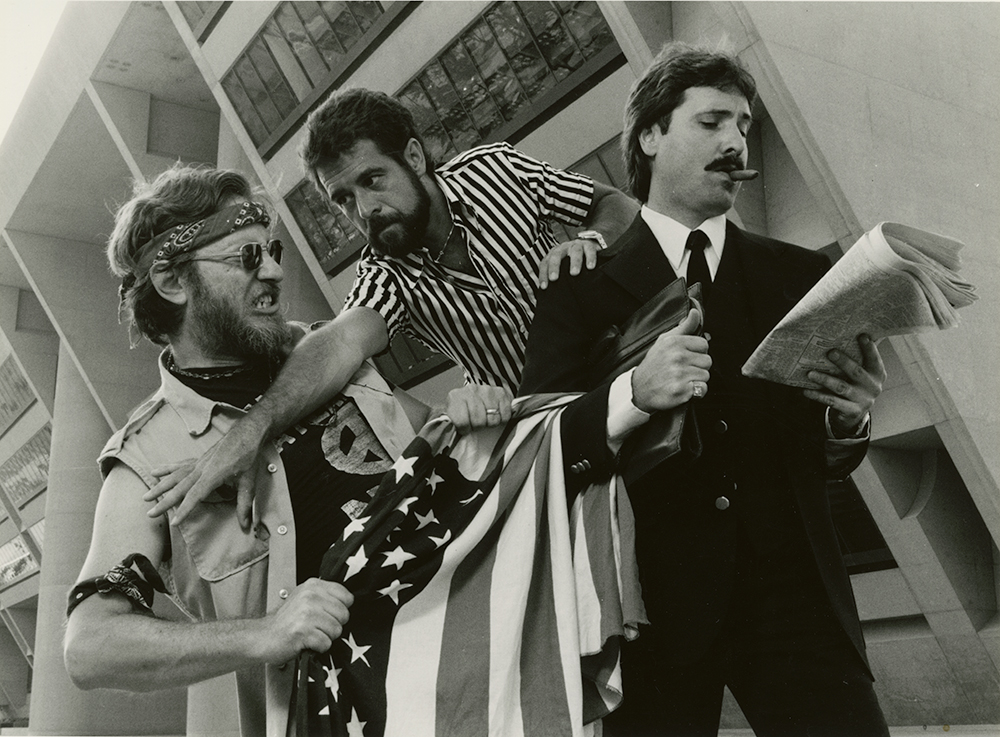

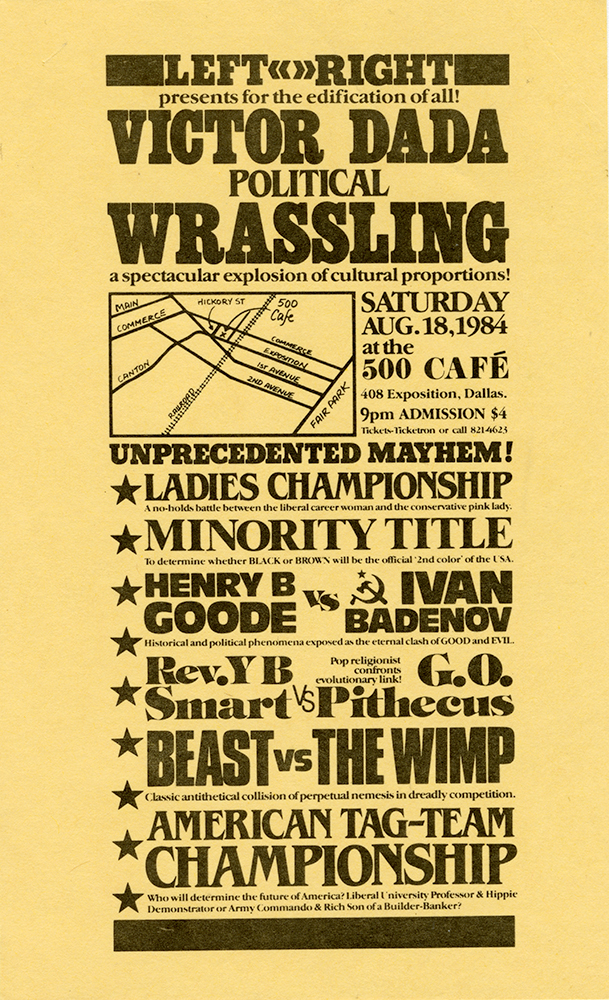

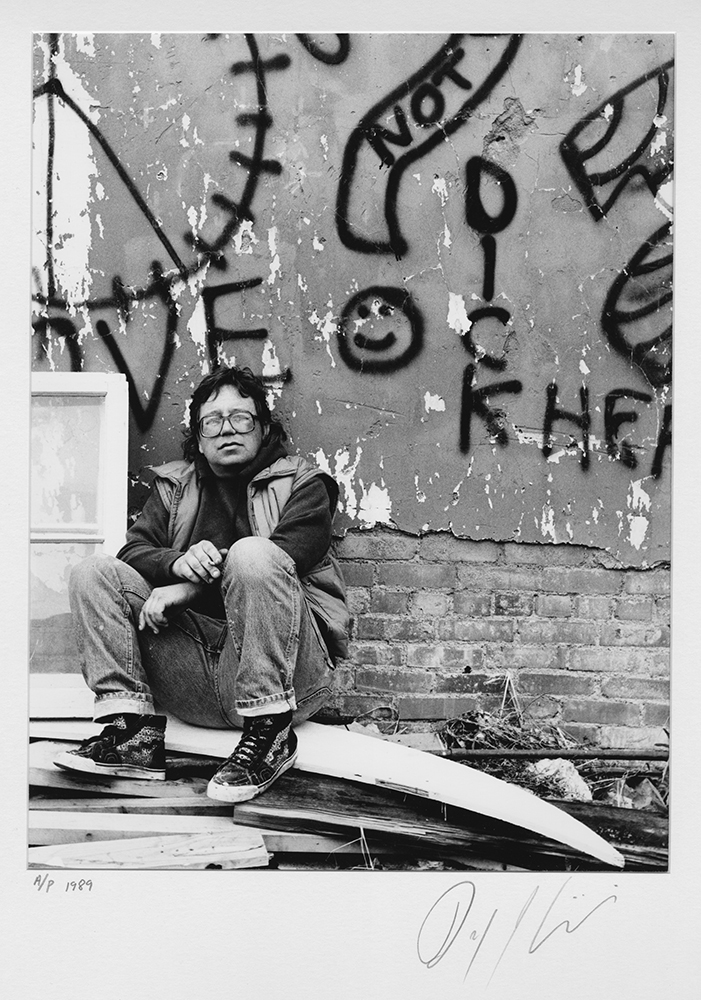

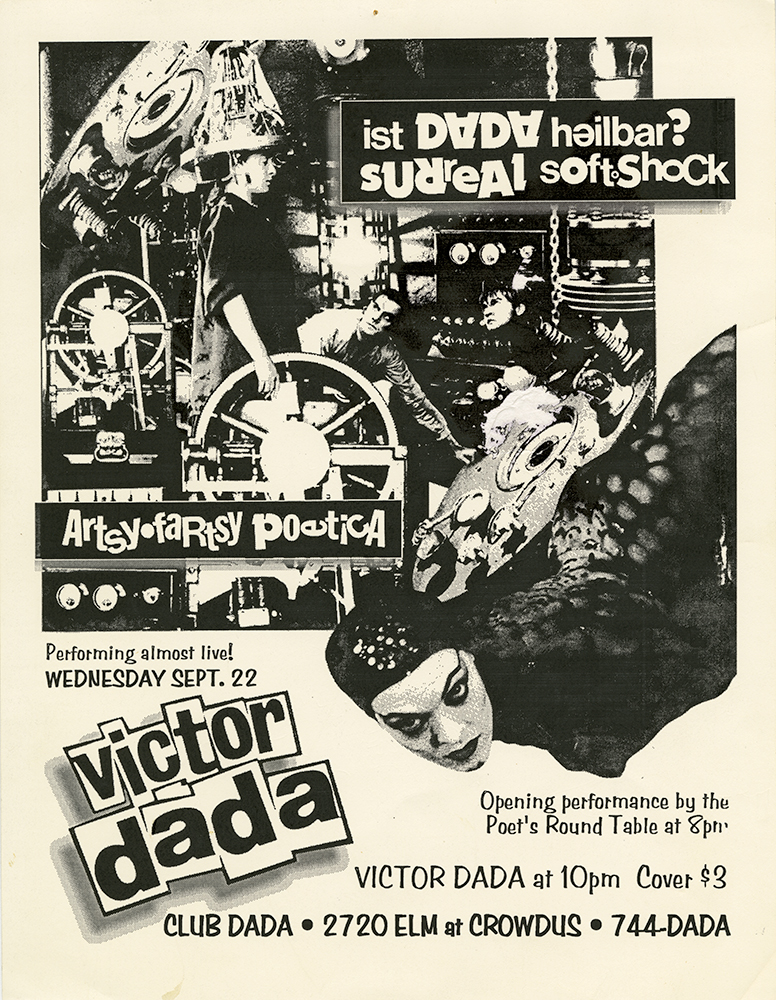

Victor Dada—a performance art, poetry, and musical group active in the Deep Ellum art and music scene throughout the 1980s—performed Political Wrassling for Left/Right. Cofounded by Joe Stanco and Gary Deen, the group was established in 1972 in Stanco’s home on Victor Street. By 1979, Tom Henvey, Farley Scott, David Border, and Doak Boettiger had joined (Fig. 6). Victor Dada’s performance pieces originally involved banging pots and pans while reciting poetry and expanded to full-blown scripted performances as the group grew in size. Political Wrassling took place on Saturday night, August 18, at Café 500 in Deep Ellum (Fig. 7). The six-bout show featured American Henry B. Goode vs. the Soviet Ivan Badenov and the Reverend Y. B. Smart vs. G. O. Pithecus. In the Ladies’ Championship, Ms. Liberty Whippet, a “liberated woman,” battled it out with Mrs. Prudence Loving, a petite “total woman” who appeared ready for “wrassling” in a corset and underwear (Fig. 8, Fig. 9).

Some of 500X’s most recognizable alumni include Vincent Falsetta, Otis Jones, Nic Nicosia, Frances Bagley, Tom Orr, Frank X. Tolbert 2, Randall Garrett, Tom Moody, Scott Barber, and Paul Booker. Other artists involved in the gallery include Texas darlings David Bates (a sale of one of his paintings is on the books), Joe Havel (1984), and James Surls, who curated the exhibition Houston at Dallas in 1980. That exhibition included work by Surls, his wife Charmaine Locke, John Alexander, Bert L. Long Jr., Jesse Lott, and Michael Tracy.

The 1980s: An Explosion of Arts Activity

With 500X breaking ground, galleries in other parts of town saw the change in the air and began relocating to raw warehouse spaces on Elm, Main, and Canton Streets. Deep Ellum’s artistic activity came together in the 1980s, when all aspects of its personality coalesced and the neighborhood became a destination for music, art, and entertainment. Artists’ studios shared city blocks with some of Dallas’ most prestigious galleries like Delahunty, DW Gallery, and Conduit Gallery, and dual venues like Theatre Gallery and Club Dada provided exhibitions of visual art between sets by locally and nationally recognized musicians.

Nearly every year in the 1980s, a new gallery or alternative space opened, and many established Uptown galleries moved to the trendy new neighborhood in search of the raw, warehouse-inspired look popularized by New York’s SoHo galleries. Collector and gallery owner Ruth Wiseman was an early convert. As a docent at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in Fair Park, Wiseman got to know the artists who had studios across the street from the Museum. As early as 1976, she teamed up with artist David McCullough to establish the gallery Oura, Inc., at 839 1/2 Exposition Avenue as an extension of McCullough’s studio in the same location. Early exhibitions in this space included artists Jennie Haddad, Michael Tichansky (Fig. 10), Judith Williams (Fig. 11), Wayne Amerine, and McCullough. When Wiseman and McCullough parted ways as gallery owners in 1981, Wiseman went out on her own. From her namesake gallery at 2816 Main Street in the heart of Deep Ellum, Wiseman and her stable of artists witnessed the rise and fall of the neighborhood art scene (Fig. 12).

Two early spaces to open up shop in Deep Ellum were not typical commercial galleries. Gerald (Jerry) Lemke and Jo Ann and Mike Hart established Peregrine Press in 1981 as the city’s first professional art print shop. Katherine Milburn and Tom Piper soon joined the staff as curator and lithographer. At Peregrine, many of Dallas’ finest artists—including Roger Winter, Andrea Rosenberg, Dan Rizzie, and James Surls—had the opportunity to work in a variety of printing media, creating monotypes, limited-edition lithographs, and silkscreens. Originally located on the corner of Peak Street and Ross Avenue, Peregrine moved in 1984 to Main Street, where it remained until it closed in May 1990 due to financial difficulties. Peregrine also ran a gallery that was temporarily located in Crescent Court in Uptown from 1982 to 1992. When Peregrine closed, the printing equipment was donated to the University of North Texas School of the Arts in 1992 to establish the Print Research Institute of North Texas (P.R.I.N.T.).

Just north of Deep Ellum, Mary Ward, Patricia Meadows, and other members of the Artists’ Coalition of Texas (ACT) established D-Art in 1981 in a 24,000-square-foot renovated warehouse as an alternative space for local artists to exhibit their work. Patricia Meadows explains the origins of the organization:

I think we were all in a state of rebellion. . . . Some more gentle, some more aggressive, but yes, rebellion. And artists started to take control of their careers and their exhibition opportunities. . . . I found the old warehouse, and it was awful. I was too innocent to know what “as is” means. . . . It means it’s a wreck and nothing works.

So, it was an artist-run organization. We were volunteering on our time. We started fundraising because we had to pay the rent. More than that, we had to pay for repairs. In fact, I’m sure that somewhere there was a sign that says, “There’s an idiot woman on Swiss Avenue that if you’d tell her you can fix her roof she’ll pay you anything.”

Those were interesting years. And then we kind of got it under control and started having exhibitions. And they were uneven because they were not juried. They were to love the artist. They were to give artists opportunities. And in order to pay the rent, we charged a small fee for having an exhibition.

D-Art became a kind of arts community center, hosting events and providing office space for more than 80 nonprofit organizations, including the USA Film Festival, the Mexican Cultural Center, and Texas Accountants and Lawyers for the Arts. By the 1990s, D-Art was known as the Dallas Visual Arts Center (DVAC) and had moved to a Victorian-style home down the street from its original location. Exhibitions focused on local and regional artists, and the annual Critics’ Choice exhibition gave emerging artists a chance to have their work assessed by local and national curators. As Edith Baker recalls, D-Art was a venue for the artists: “There was nothing like it. There’s no place that artists could go, they were just rejected back and forth from galleries to museums to everything. But there was one place where they could go and they would be accepted.” Directors included Vicki Meek, Katherine Wagner, and Joan Davidow, who led DVAC’s expansion into its current location in the Design District, where it is known as the Dallas Contemporary.

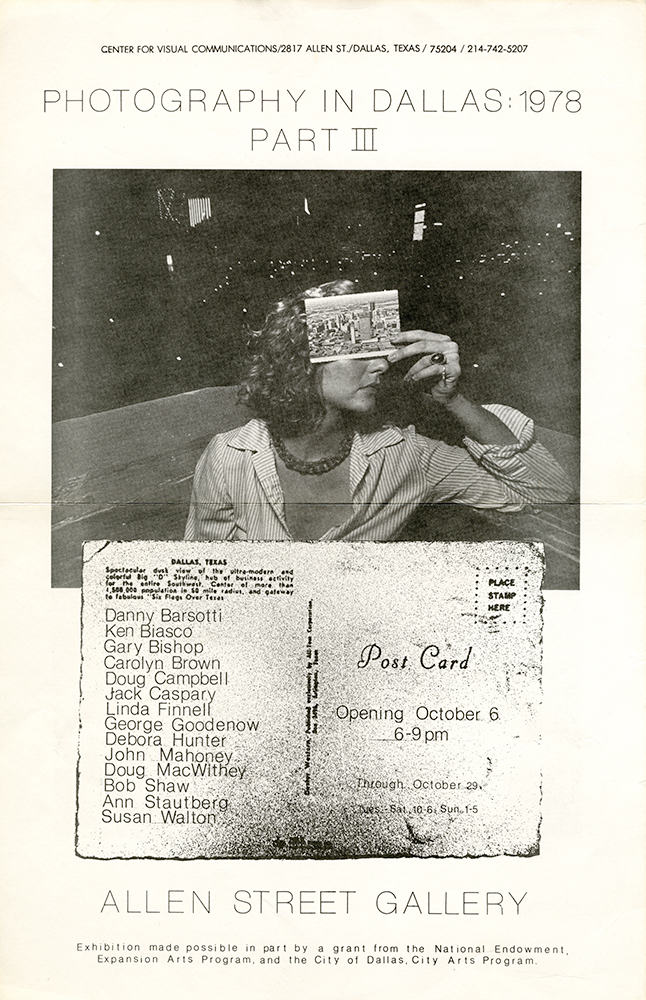

Deep Ellum welcomed another nonprofit space in 1982 when the Allen Street Gallery moved from Uptown to larger quarters at 2913 Canton Street in Deep Ellum. Allen Street focused primarily on supporting the photographic arts and was administered by the nonprofit Center for Visual Communications. Established in 1975 by a group of local photographers, it had the dual purpose of educating the public and providing a place where area photographers could show their work in a formal gallery setting. The recurring Third Sundays exhibitions, held on the third Sunday of every month, increased exposure for artists and invited them to sell their work directly to the public. Juried exhibitions like Photography in Dallas, 1978: Part III (Fig. 13) and the Texas Women’s Photography Show (1979) presented a broad glimpse of photography in Dallas and across the state. Allen Street also exhibited work in other media, including local artist David Bates’ MFA thesis show for Southern Methodist University in 1976 and The Myth, a thematic group show of works in all media by more than 30 local artists, also in 1976. Shortly after the gallery moved to Deep Ellum, it hosted Counter Angel in 1983, a one-woman performance adaptation of Jo Harvey Allen’s book The Beautiful Waitress, performed by the writer and directed by Joan Tewkesbury.

In spring 1983, Allen Street Gallery expanded its board of directors to develop a broader base, and a full-time director was appointed in 1984. Within a year of moving to Deep Ellum, the new location proved to be too much to handle, and the gallery was forced to close. It reopened in 1984 at 4101 Commerce Street near Fair Park.

Delahunty Gallery opened its doors in Deep Ellum in 1982 in a warehouse at 2701 Canton Street formerly occupied by artist George T. Green. The gallery was established in 1974 by Laura Carpenter, Murray Smither, and Virginia Gable in Smither’s old gallery space on Allen Street. It then moved to Cedar Springs in Uptown. Delahunty showed work by national and international artists alongside local and regional talent. Artists who made a name there include Vernon Fisher, Nic Nicosia, Danny Williams, Dan Rizzie, and Robert (Daddy-O) Wade. The first exhibition at the Deep Ellum location was a group show of sculpture by Californian Michael Lucero, Italian Italo Scanga, and East Texan James Surls. Subsequent exhibitions included solo shows of Vernon Fisher (1982), Nic Nicosia (1983), Christo (1983), Tom Wesselmann sculpture (1983), and Danny Williams and Andy Warhol (1984). The gallery closed in 1984 when owner Laura Carpenter shifted focus to blue-chip artists under a new name, Carpenter + Hochman. As a result of the shake-up, Carpenter’s director Hiram Butler moved to Houston to open his own space with the help of two Delahunty artists, Vernon Fisher and James Surls.

In 1983, DW Gallery (formerly DW Co-op) moved from its original location on the second level of a small building at the corner of McKinney and Hall Streets in Uptown to the second floor of the Herling Building at 3200 Main Street. In its spacious new 2,400-square-foot space, DW began to show more work, and its exhibitions included large-scale sculpture. The inaugural exhibition, Construction/Site, included work by gallery artists Linnea Glatt, John Hernandez, Rick Maxwell, Dalton Maroney, and Lee N. Smith. The artists installed large-scale works that emphasized the gallery’s increase in square footage. Glatt’s 12-by-8-foot structure, Form for a Place to Gather, had recently been on view in the meadow of the Connemara Conservancy Foundation north of Dallas (Fig. 14); Hernandez’s large-scale wall relief, Big Daddy, Dream Glass, was installed to be viewed in the round opposite Maxwell’s 12-foot-long triptych of colorful patterns, Barrio Barricades. Rounding out the exhibition were Maroney’s three 20-to-25-foot abstract boat forms and Smith’s two large canvases, Mud City and Spinning Lights and Electric Smoke.

Subsequent exhibitions in DW’s Deep Ellum space included a solo show of David Bates (1983); Nancy Chambers: Constructions and Drawings (1984); Linda Finnell: Photographs (1984); Lee N. Smith III: Recent Works (1985); Julie Cohn and Susie Phillips: Recent Work (1986); and Martin Delabano: Recent Works (1987). The gallery closed in 1988 amid financial problems. Its final exhibition, The Last Show, was guest-curated by DW cofounder Linda Samuels Surls and featured work by the six other cofounders.

The gallery district had officially migrated to Deep Ellum by the mid-1980s. A slew of galleries opened, starting with Nancy Whitenack’s Conduit Gallery in 1984. Whitenack had no prior gallery experience, and she remembers that opening the gallery was “kind of a leap of faith”:

I had to really learn everything about what you do to run a gallery. How you support artists, where you find clients, and the whole ball of wax. I was a teacher previously, and I have always loved the visual arts. I’ve been an inveterate gallery- and museum-goer all of my life, so that part I kind of knew about; but running a gallery is a whole different thing. It’s been quite a journey. I opened the gallery when the economy was in the tank. The good part of that, probably, is I had nowhere to go but up. I started in Deep Ellum on Elm Street, and my former husband and I worked on the space. We literally did the plumbing and all the sheetrocking. Every part of it was an enterprise that we put our blood, sweat, and tears into, so I feel like I can do most anything, out of necessity.

Conduit has always focused on midcareer and established artists and programs. Its Project Room displayed experimental work by artists not represented by a gallery. Early exhibitions at the original location in Deep Ellum included Robert Barsamian: Paintings and Drawings (1988); The Self-Portrait (1988), which featured self-portraits by gallery and nongallery artists like Nancy Ferro, Laray Polk, Bill Haveron, Jack Mims, and John Hernandez; and the group exhibition Inquiring Minds Want to Know, which featured Core Fellows at the Glassell School of Art in Houston--Bill Davenport, Aaron Parazette, and Paul Francis Forsythe (1994). Conduit Gallery earned a reputation for strong exhibitions in a variety of media: The Language of Sculpture: An Outdoor Exhibition of Works by Yonekichi Tanaka and Tom Orr, with small works on view in the gallery (1996); Other Systems: New Paintings by Vincent Falsetta (1998); Delabano: Full Circle (2000); and Susie Phillips Travels Abroad (2001). In 2002, the gallery was one of the first to move into the Design District, where many galleries have since relocated.

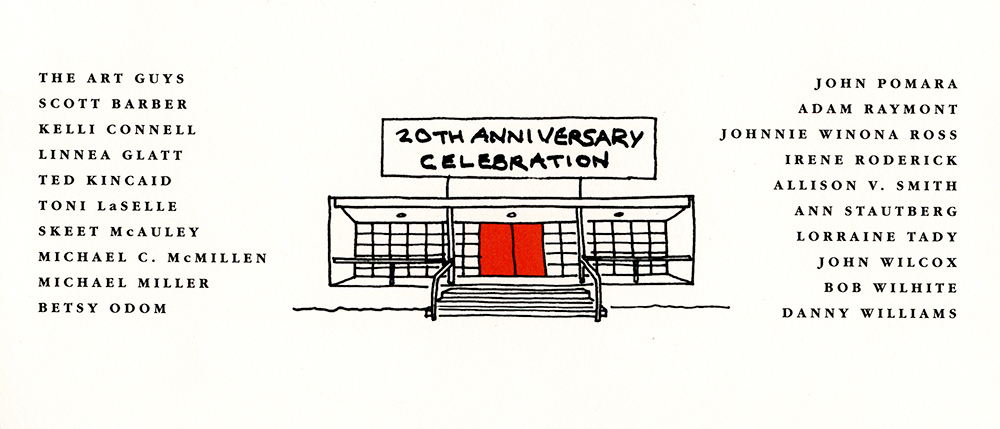

Barry Whistler, a former director of Delahunty Gallery, opened his namesake gallery just down the street from Conduit in 1985. At Delahunty, Whistler had gained valuable experience working under Laura Carpenter and Murray Smither, and many Texas artists represented by Delahunty ended up with Whistler when Carpenter shifted her focus. Whistler attended North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas) and worked as a preparator at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts and the Fort Worth Art Center (now the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth). A two-year stint at Ace Gallery in Los Angeles gave him the experience he needed to take the helm of Delahunty in 1979. Whistler Gallery has focused on midcareer and established regional artists, representing well-known Dallas and Texas artists Scott Barber, Linnea Glatt, Toni LaSelle, Tom Orr, John Pomara, Andrea Rosenberg, John Wilcox, and Danny Williams. It is the kind of space local emerging artists aspire to, understanding that a spot on Whistler’s roster means the artist has made it in the Texas art world (Fig. 15, Fig. 16).

Soon restaurants, bars, and music venues started filling in the gaps between galleries and artist studios, expanding Deep Ellum’s identity as an entertainment district. Savvy entrepreneurs saw the value in the crosspollination of music and the visual arts. Russell Hobbs opened Theatre Gallery in a Commerce Street warehouse in August 1984. The space doubled as a visual arts gallery and performance venue for New Wave musicians and was important to the developing music scene and the neighborhood’s revival. Using the slogan “Throw away your polo shirt and become the artist you always wanted to be!” Theatre Gallery hosted nationally recognized groups like the Flaming Lips, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Jane’s Addiction and gave local artists like Bill Haveron, Ron English, and Jeff Robinson exhibitions between musical sets.

Members of the performance collective Victor Dada established Club Dada in 1986 as a permanent home for performance art in Dallas (Fig. 17). After years of a nomadic existence, performing in a variety of spaces—Paperbacks Plus bookstore in Mesquite (1981), DW Gallery (1982), the Stoneleigh P Bar (1982), and the Bath House Cultural Center—they purchased a building at 2720 Elm Street. Like Theatre Gallery, Club Dada doubled as a performance art and music venue that helped launch the career of the Dallas-based band New Bohemians, led by singer-songwriter Edie Brickell, while giving performance artists a place that welcomed the strange and avant-garde. During Monday Night Feedback at Club Dada, the sound on the bar’s television was turned down during regular football programming to allow Gary Deen and Farley Scott to improvise their own commentary. Weird Wednesdays featured “spontaneous music”—collaborations between musical acts like BL Lacerta and the audience. In 1991, artist and gallery owner John Held Jr. performed Invisible Impressions, a work in which Held and fellow artist Paula Maples rubber-stamped each other with invisible ink that became visible under certain conditions on stage. In later years, Club Dada became more focused on musical acts. It closed in 2003, reopening several years later under new ownership.

Eugene Binder was established in May 1986 in the space that had been occupied by Laura Carpenter's Carpenter + Hochman. Binder’s experience as a gallery owner and art dealer was quite extensive by the time he established his own space. Born and raised in a suburb of Detroit, he moved to Texas in the late 1960s to attend Northwood Institute, where he took art history courses taught by the Fort Worth Art Center’s Henry Hopkins. While at Northwood, Binder started working for artist Chapman Kelley at his Atelier Chapman Kelley and slowly became involved in the Dallas art scene, doing odd jobs for artists Alberto Collie and Mac Whitney. He parlayed the connections he made in Dallas into a position as assistant curator at the Laguna Gloria Museum of Art in Austin, where he was responsible for the 1978 major career retrospective of minimalist artist Carl Andre. Before returning to Dallas in 1984, Binder worked as the director of former Dallas gallery owner Janie C. Lee’s Houston gallery, helping to organize major exhibitions by Jasper Johns and Joan Mitchell.

Laura Carpenter hired Binder in 1984 to direct her Dallas gallery Carpenter + Hochman, an offshoot of Delahunty Gallery established when Carpenter expanded her business to New York and narrowed her focus to blue-chip artists. Binder organized exhibitions of work by David Hockney (1985), Piet Mondrian (1985), Dan Rizzie (1985), Christo (1986), and others. The new focus and dual locations proved to be too much for Carpenter, who was forced to close in 1986. Binder remained in the location until he could establish a gallery that would be independent of the Carpenter legacy:

Well, I actually didn’t open my own space. She [Carpenter] shut down and I asked her if she’d lease me the building and she came up with this number. At the time, I thought this was okay. And so for the rest of the year, I was in there, or maybe not even a year, it was maybe like March through December. And then I had a temporary space while this other building was being renovated, a building of David Gibson’s, which was interestingly enough a former bindery.

As owner and director of his own space, Binder opened with an exhibition of eight contemporary Italian artists, including Francesco Clemente, who was concurrently the subject of a solo exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art. Later exhibitions at Binder’s gallery featured a variety of regional and national talent, including Oak Cliff artist Bill Haveron (1987); works on paper by David Bates (1989); Dallas-based artist Sam Gummelt (1989); New York–based artists Ann McCoy (1989) (Fig. 18) and Jonathan Lasker (1992); and University of Texas at Dallas professor John Pomara (1994).

In April 1990, understanding the business adage of grow or be stagnant, Binder expanded to Germany, opening the Binder Galerie in Cologne with the Texas Show. Featuring artists from Binder’s stable—Dan Rizzie, David Bates, Sam Gummelt, Barbara Simcoe, Ken Luce, and Gregory Horndeski—the exhibition brought a taste of Texas to the German art market. As Binder explained, “it’s pretty much a given that everybody from Buddy Holly to Van Cliburn can’t get any recognition unless they leave Texas. The point was to get the artists I’m representing into a different setting [and] out of the stigma of regionalism.” Subsequent exhibitions at Binder Galerie included solo shows of Australian artist Andreas Tschinkl and Dallas artist Sam Gummelt and the group show Outsider Art, featuring work by naïve, primarily African-American, painters. By 1992, the economy forced Binder to rethink his German location, and he formed a loose alliance with German dealers Gunar Barthel and Tobias Tetzner, who took the lead on the Cologne space. In Dallas, Binder maintained the Eugene Binder space for another four years before closing in 1996 and moving to Marfa in West Texas, where he currently resides and continues to organize exhibitions at his namesake space.

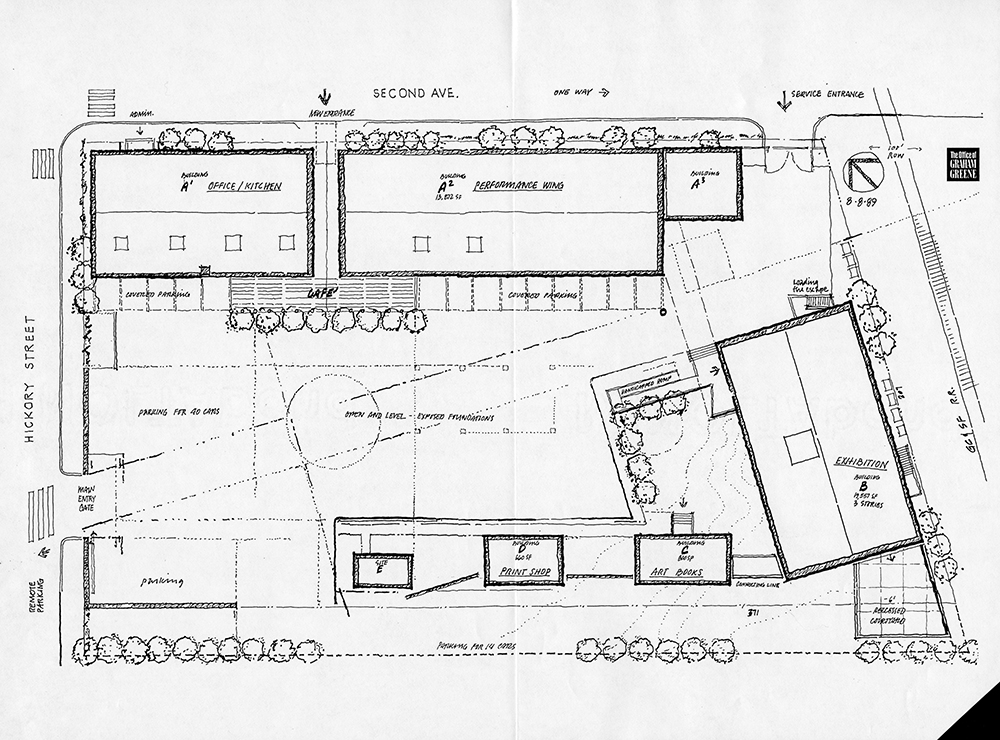

As an alternative to commercial galleries, artists could get involved with the Hickory Street Annex. In 1989, Richard Brettell, Dallas Museum of Art director, and Jeff Kelley, director of the Center for Research in Contemporary Art at the University of Texas at Arlington, proposed an offsite extension of the Dallas Museum of Art that would offer cutting-edge programs not always possible or appropriate for a museum’s primary exhibition space. The focus was to be contemporary artists working and living in the region, with spaces designed to support work that did not fit within the confines of a traditional gallery (Fig. 19). When funding failed to materialize, artists took over the space and ran it themselves. In 1990, local artist Frances Bagley curated the exhibition The Vessel, a group show featuring different artists’ interpretations of the subject. The catalogue had full-color illustrations and an essay by Brettell. Other artist-organized exhibitions included Escape from New York (1991), with work by Ludwig Schwarz, Laura Wilson, and Elise Cohen (Fig. 20). Shawn Patrick Anderson and Christopher Todd Hogg established the Museum of Agenda and Transgression (M.O.A.T.) in 1994 in the lower level of the Hickory Street Annex. The gallery showed multimedia installations dealing with the icons, ideas, and issues of pop culture. Exhibitions featured John Hernandez, Helen Altman, Joe Allen, Joe Havel, and Pamela Nelson.

The 1990s and Beyond

Increased development had pushed many artists out of Deep Ellum by the early 1990s. Patricia Meadows remembers a moment that characterizes the atmosphere at the time:

Once a year there would be an Art Walk which went over a weekend. . . . And so it was a great two days, but it was also a little tough. At the end of the weekend we would all meet at the Sons of Hermann Hall, and . . . they would open it up and have music and gumbo. And it was sunset, and the cool breeze had just started. I was sitting on the fire escape, and there were people below—artists, friends. Somebody had a guitar, everybody was singing. It was such a community moment, it was just so dear, an innocent community moment where you just go, “I know these people, I love these people. We are all crazy, there is no way to explain why I’m here,” but it was . . . an innocent moment.

And you realize, because city code was gearing up to turn all of those artists out, Deep Ellum was beginning to become sort of a SoHo, chi-chi area. The rents were going up, the artists were going to have to leave, and they did. They were all sort of dispersed in the next two or three years.

But it was a community moment that was really sweet and innocent, and people were just working hard toward a goal of getting the art out there. It was lovely.

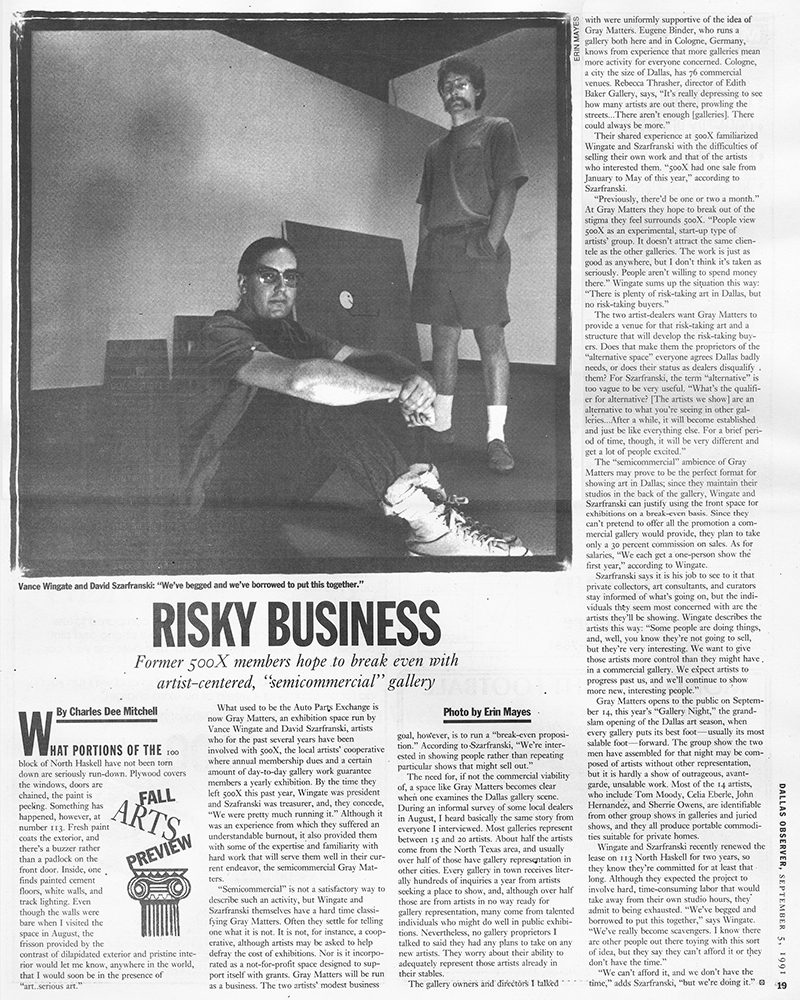

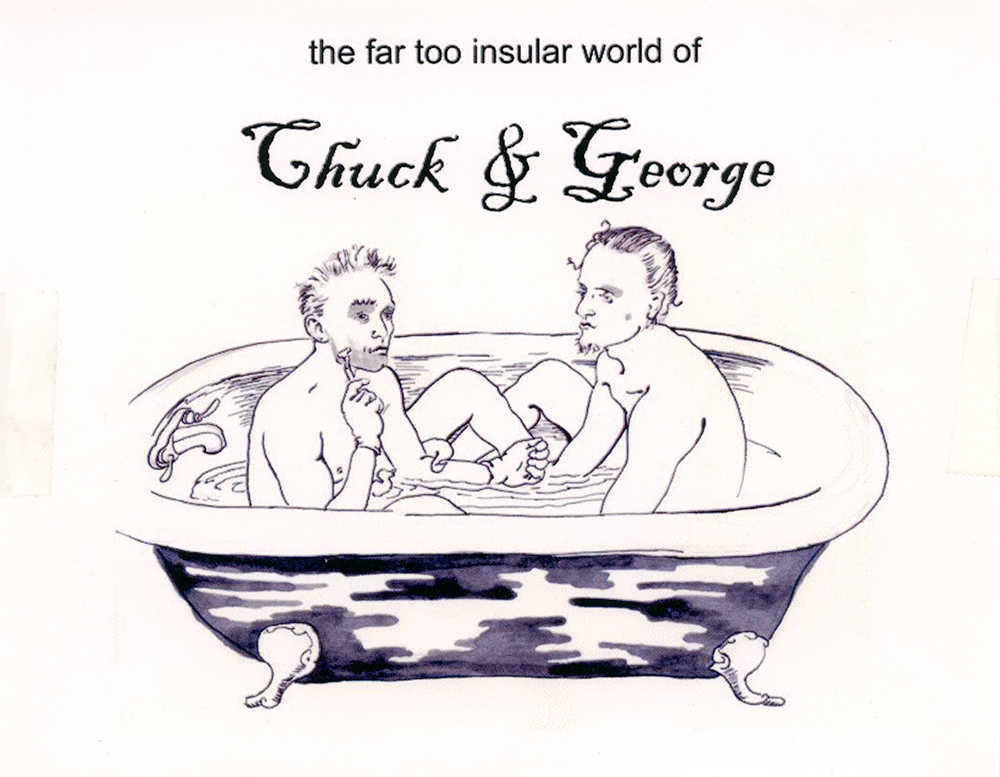

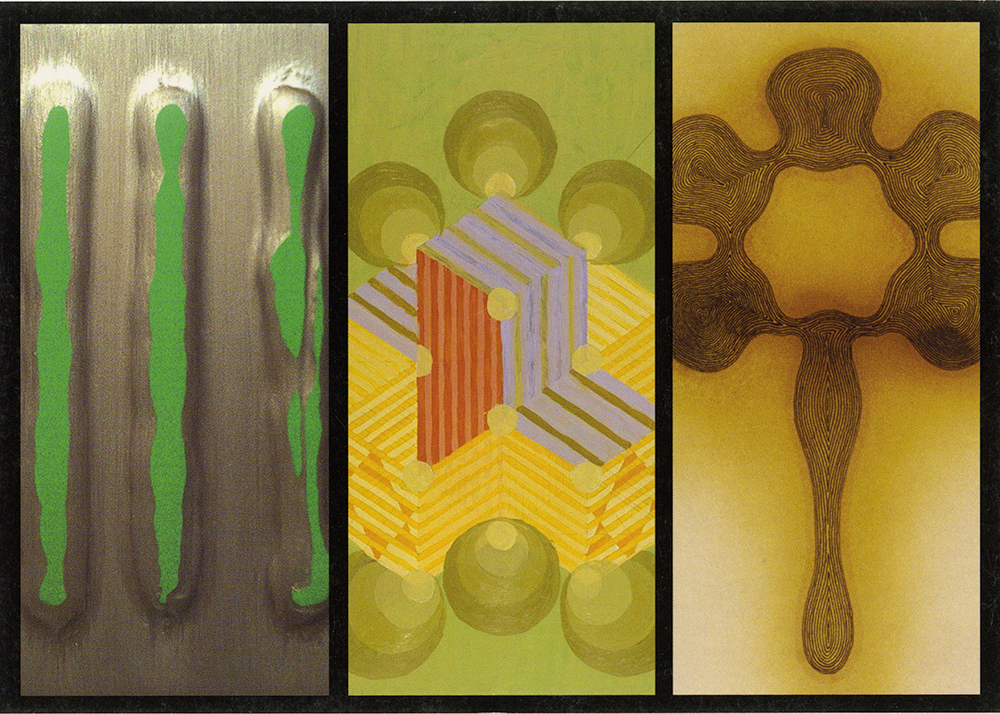

Several commercial galleries and nonprofit spaces kept the neighborhood of Deep Ellum an active art community through the 1990s. David Szafranski and Vance Wingate, two University of North Texas alums and former members of 500X, established Gray Matters Gallery in 1991 (Fig. 21). The inaugural exhibition was a group show of artists who would remain staples of the Gray Matters roster: Szafranski, Wingate, Celia Eberle, John Hernandez, Mike Kennedy, Dottie Allen (Love), Tom Sale, Sherry Owens, Connie Cullum, Trish Nickell, Randy Bolton, and Tom Moody. Off and on for nearly 15 years, Gray Matters was the place to see cutting-edge work by emerging and midcareer artists working in North Texas. On the extensive list of artists who have shown with Gray Matters are some of Dallas’ most recognizable artists of the younger generation, including artist duo Chuck & George (Brian K. Jones and Brian K. Scott), CJ Davis, Brad Ford Smith, and Noah Simblist (Fig. 22, Fig. 23). Szafranski and Wingate thought of Gray Matters as an alternative space more than a commercial gallery, and they never made large profits. What mattered to them was presenting challenging work and giving artists opportunities to take chances.

Gray Matters Gallery represents a time in Dallas when a generation of artists and writers coming out of UNT were getting together, working, and exhibiting in venues around the city. These artists were considered just shy of warranting the attention of major established galleries like Barry Whistler or Gerald Peters Fine Art. Taking advantage of their status below the radar, they did their own thing without the pressure that comes with forcing a career as a professional artist. Many who got their start at Gray Matters have gone on to gain representation at major North Texas galleries. Though Gray Matters officially closed in 2005, Wingate still organizes exhibitions and enables other local artists and curators to put together shows of their own in an environment that is still buzzing with the energy it had some 15 years ago.

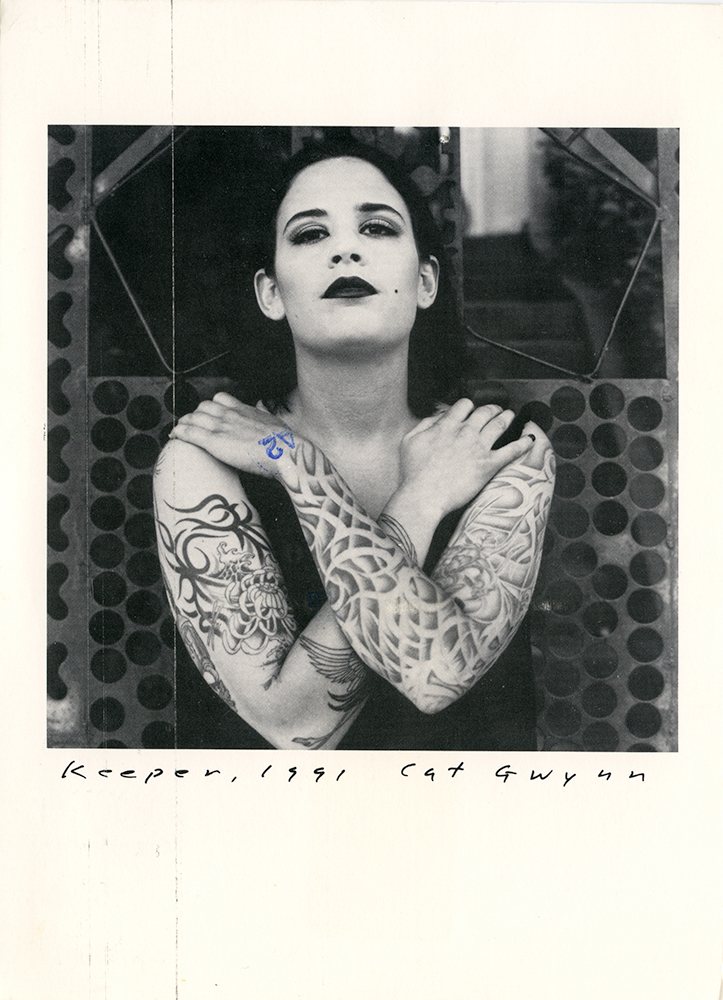

Founded in 1992, 5501 Columbia Art Center was a nonprofit community space featuring an interdisciplinary program with topics ranging from books to arts to jazz. One of its two inaugural shows, Forever Yes: Art of the New Tattoo (Fig. 24), explored the aesthetics of body art. The center’s mission reflected a larger movement in the contemporary art scene during the 1990s to examine the diversity of identity. From 1995 until its closing in 2001, it housed the Texas African-American Photography Collection and Archive, now run by Dallas nonprofit organization Documentary Arts, Inc.

Deep Ellum in the New Millennium

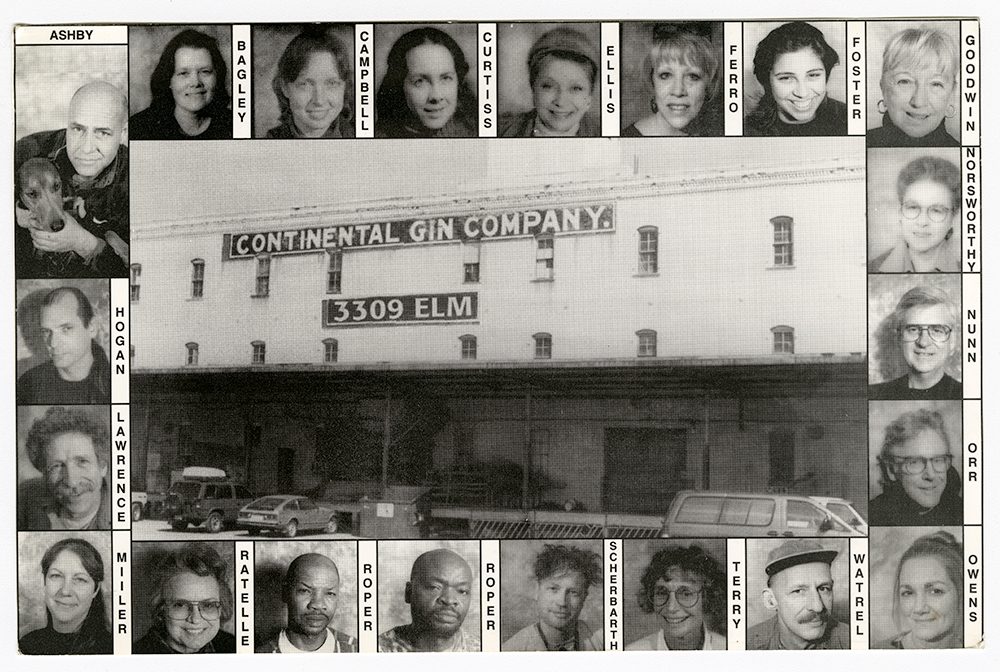

During the 1990s, arts activity in Deep Ellum suffered somewhat, as the neighborhood was always on the edge of crime and the demimonde culture of decades past surfaced once again. Sculptor duo Tom Orr and Frances Bagley, together with Dallas artist Albert Scherbarth, had taken control of the 100-year-old Continental Gin Building at 3309 Elm Street in 1986 and spent the next six years renovating it for use as artist studios. In 1992, the first artist signed a lease there, and by 1997, the 60,000-square-foot building was home to 30 artists and hosted annual Open Studio tours (Fig. 25). The Continental Gin Building helped maintain local artists’ ties to Deep Ellum through the slow decline of the 1990s and bridged the gap between the 1980s heyday and the neighborhood’s resurgence in the new millennium.

In 2006, Dallasite Christina Rees opened the gallery Road Agent at 2909 Canton Street. A former director of Angstrom Gallery and former writer and editor for local publications The Met, D Magazine, and the Dallas Observer, Rees had developed an aptitude for spotting emerging talent. Her gallery focused on emerging and midcareer artists. It featured group thematic exhibitions like Ambush: Stand and Deliver (2006), which pulled together a group of unannounced artists with fresh work each week over the summer; the group exhibition The Audience Is Listening (2007); and solo exhibitions by New York sculptor Ryan Humphrey (2006), Denton-based Elliott Johnson (2006), Los Angeles abstract painter Evan Lintermans (2006), Fort Worth sculptor Bradly Brown (2006), and Dallas sculptor and installation artist Margaret Meehan (2008). The financial crisis in 2008 had a deep impact on many gallery owners, including Rees, who closed Road Agent with the group show Party at the Moontower. The loss of midrange buyers and the increased conservatism of high-end collectors left little room for a gallery like Road Agent, whose focus on emerging artists and experimental work was deemed too risky for this changing collector market. Galleries that survived the 2008 market crash were either well established or, like Brian Gibb and Mark Searcy’s Art Prostitute, had developed a niche market in Dallas.

Gibb and Searcy are graduates of the University of North Texas, where they both studied art and communication design. Gibb recalls how he eventually decided on this focus:

I studied drawing and painting and communication design kind of simultaneously until I got to a point where Vincent Falsetta was like, “Okay, you’ve got it. You’ve got to pick a team. You can’t do both. You’d be splitting your focus. . . .” So I actually decided to finish my degree in communication design because to me I knew that my interest in art and studio practice and making things . . . was going to continue on with me regardless.

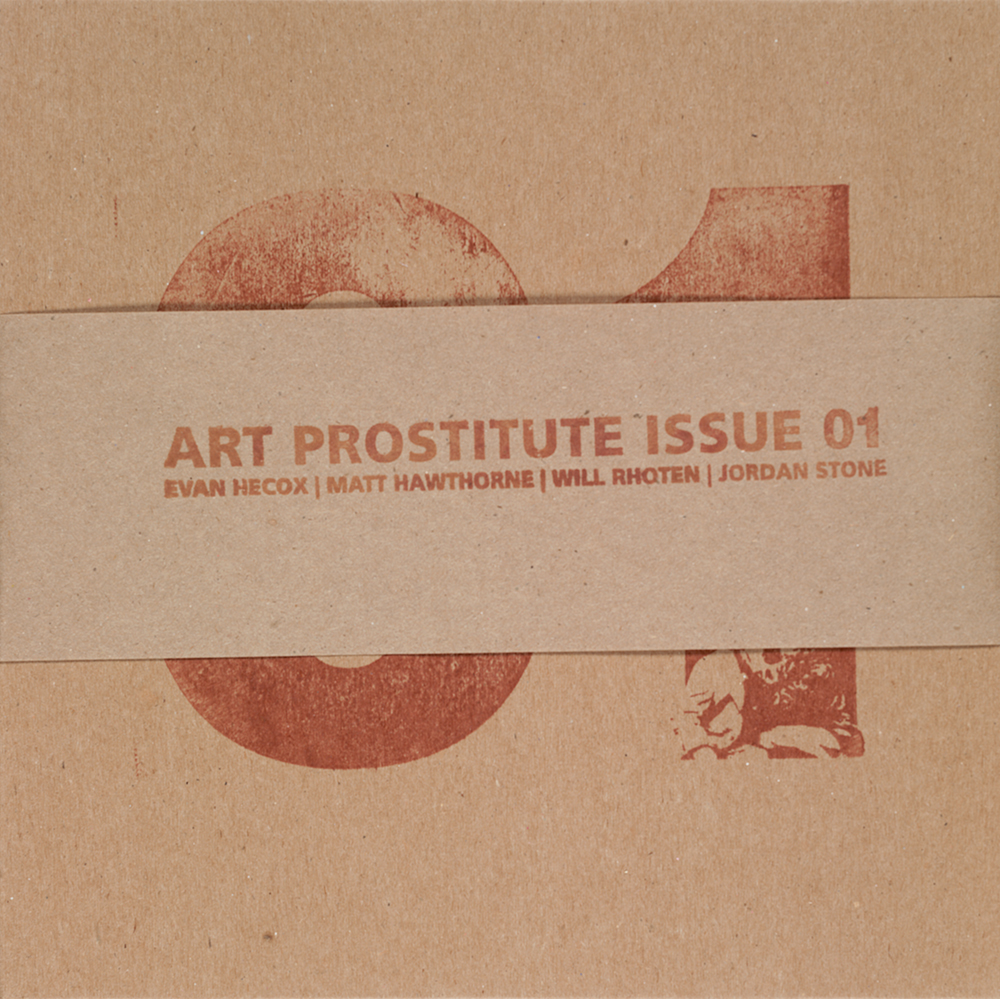

The young artists’ decision to pursue graphic design provoked negative attention from some of their friends and colleagues, who accused the pair of selling out. So when they parlayed their interests into a sleek quarterly magazine, they named it Art Prostitute (Fig. 26). As Searcy explained, “the whole premise is that you can be an artist and make money.” Gibb described how the idea came about:

[Mark] and I had a lot in common. We’re both skateboarders. We both like art. We both made art. Art very much influenced what we did on a design level and vice versa. . . . We just started talking about doing a publication. At the time, there is this sort of thing that was happening where artists were being commissioned to do things like sneakers and apparel lines and stuff like that. Obviously, the crossover between art and skateboarding and skateboard graphics, people like Ed Templeton and Evan Hecox, artists like that were really big influences.

Launched in 2003, Art Prostitute featured artists Gibb described as occupying that crossover space between art and skateboarding, including formerly underground street artists Shepard Fairey and Dave Kinsey. A year after the publication’s debut, Gibb and Searcy opened a gallery by the same name at 210 Hickory Street in Denton, where they displayed the work of artists featured in their magazine and sold it at a variety of price points. The inaugural exhibition Roll Call featured handprinted skateboard decks, silkscreened book covers, and prints, all priced between $40 and $1,000. In 2006, Gibb and Searcy decided to move their gallery to Deep Ellum.

Art Prostitute’s first exhibition in the new location included paintings by Los Angeles artist Dave Kinsey. Among the gallery’s other shows were Regal Row (2006)—featuring new work by Oregon painter Evan B. Harris, Dallas painters Mark Nelson and Will Rhoten, and California-based painter Joseph Stein—and Low Tech High Life (2006), featuring new work by Californians Jeremy Fish, Mel Kadel, and Travis Millard and Austin painter Michael Sieben. In 2007, Searcy left the gallery to pursue a career in Portland. Gibb continued the space under the new name The Public Trust. The duo’s magazine Art Prostitute published its final issue in 2006.

Like its predecessor, The Public Trust showcases emerging and established artists and limited-edition prints. Examples of the gallery’s diverse program are group exhibitions like On Solid Ground: A Group Exhibition of Work by Kevin Bell, Colin Chillag, Christi Haupt, and Steven Larson (2009), which brought together artists from all over the globe to explore the idea of place, real and imagined; a solo exhibition of the work of nature illustrator-painter Charley Harper (2009); and the recent exhibition of prints by Shepard Fairey (2012).

Newcomers Kirk Hopper Fine Art and Liliana Bloch Gallery offer Deep Ellum distinctly different experiences with contemporary art. Dallasite Kirk Hopper established his gallery in 2011 as a space for local midcareer and established artists. Its inaugural exhibition was a solo show of work by large-scale abstract sculptor Mac Whitney, while subsequent exhibitions have included the group exhibition Sex/Twist (2011), featuring work by artists who visually represented French philosopher Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality; Forrest Bess: 100 Years (2011), featuring Texas painter Forrest Bess alongside artists who were influenced by or worked with him; and Between Heaven and Earth: New Work by Roger Winter (2012).

Liliana Bloch Gallery, the newest addition to the neighborhood, opened its doors in the spring of 2013. Bloch stepped out on her own based on her experience as director of McKinney Avenue Contemporary in Uptown and Kirk Hopper Fine Art. Artists in the gallery’s diverse stable include Vietnamese Du Chau; Salvadoran Mayra Barraza; Dallasites Ann Glazer, Vince Jones, Sally Warren, and Iranian-born Mona Kasra; Fort Worth-based Leticia Huckaby; and New Yorker Ryan Sarah Murphy, who inaugurated Bloch’s gallery with a show of her found-object collages.

The Power Station opened in 2011 with an exhibition by Los Angeles painter Oscar Tuazon. As a nonprofit exhibition and educational space, The Power Station operates outside the mainstream commercial gallery system, bringing to Dallas artists whose work defies commodification. Installations like Deluxe (2012) by Virginia Overton, whose pickup truck in the gallery was sculptural gesture, and Drip Event (2013) by Tobias Madison, Emanuel Rossetti, and Stefan Tcherepnin, who installed a self-circulating water system throughout the two levels that created a shallow lake on the second level, are examples of work that commercial galleries do not typically support. Educational programs—like the video art series Four Nights Four Decades, curated by local artists and professors Michael Morris, Nadav Assor, Benjamin Lima, and Jenny Vogel—are another aspect of The Power Station’s diverse offerings.

Recent University of Texas at Arlington graduate Kevin Rubén Jacobs established Oliver Francis Gallery (OFG) in 2011. Located at 209 South Peak Street in East Dallas just north of Deep Ellum, the intimate space is dedicated to showing experimental work by emerging and established artists, local and international. Exhibitions have featured a variety of media: installation, new media, performance, and conceptual art, with solo exhibitions of artists like painter and recent Rhode Island School of Design MFA graduate Francisco Moreno (2011), Dallasite Jeff Zilm (2011), and Berlin-based conceptual sculptor Rachel de Joode (2012). Group exhibitions include SNAFU (2012), with work by artists Darja Bajagić, Andrew Birk, Kasumi Chow, Kristen Cochran, CJ Davis, Lauren Elder, Desiree Espada, Claire Fontaine, Michael Mazurek, Drew Olivo, Lana Paninchul, Michelle Rawlings, Ludwig Schwarz, Kevin Todora, Michael Wynne, and Jeff Zilm. Off-site curatorial installations have included She Was Long Gone by New York artist Kristin Oppenheim and Perishabel, featuring artists Pierre Krause, Nick DeMarco, and Luis Miguel Bendaña, as part of Deep Ellum Windows in spring 2013; and the group exhibition Skim Milk at Interstate Projects in Brooklyn, New York, in summer 2013. OFG has also collaborated with local artist collectives such as HOMECOMING! Committee of Fort Worth for the group exhibition and performance competition Hands on an Art Body (2012) and Dick Higgins Gallery for the group exhibition DB12 Volume 1 (2012).

Today Deep Ellum retains some of the same qualities that helped put it on the map in the 1980s: a vibrant music scene at venues like Club Dada and the Prophet Bar and an equally vibrant contemporary arts scene. The continued success of Barry Whistler Gallery and The Public Trust help keep the commercial gallery system relevant to national and international trends in contemporary art, with Kirk Hopper Fine Art and Liliana Bloch Gallery rounding out the neighborhood’s strong group of commercial galleries. Experimental and artist-run spaces like the established 500X and newcomers The Power Station and Oliver Francis Gallery continue to introduce Dallas audiences to alternative experiences created by local and international emerging and midcareer artists in a variety of media.