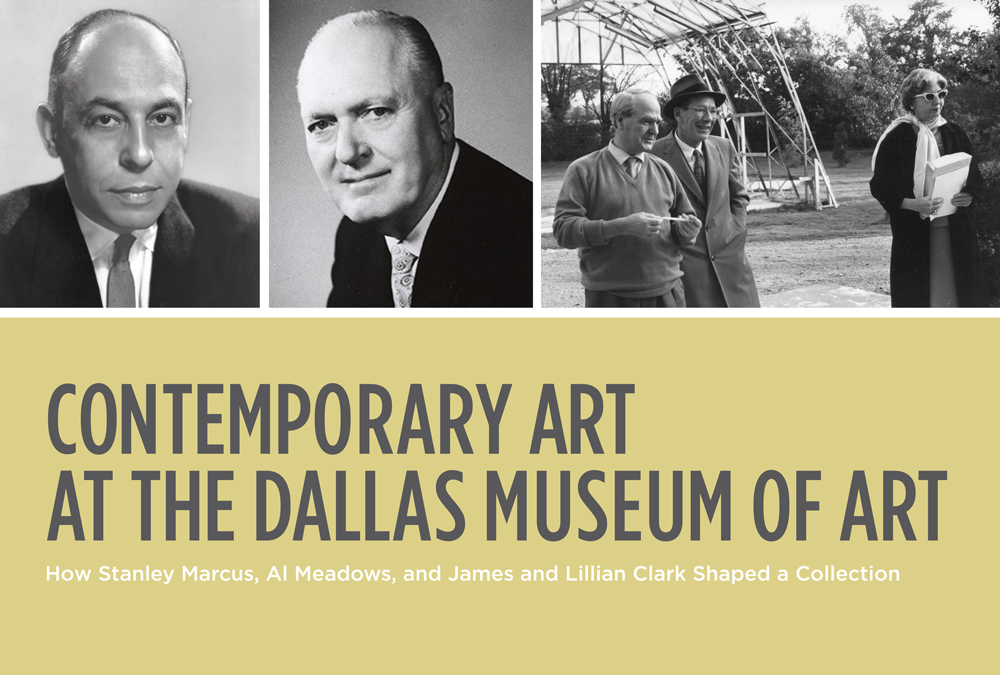

The Dallas Museum of Art is proud to present DallasSITES: A Developing Art Scene, Postwar to Present, which celebrates and documents 50 years of North Texas’ bold and distinctive contemporary art community. Organized by neighborhood, this digital publication focuses on seven Dallas communities— Fair Park-South Dallas, Uptown, Oak Cliff, Deep Ellum, Arts District-Downtown, Design District, and surrounding university communities—to trace the unique development of contemporary art in each geographic area and their collective contribution toward making Dallas the vibrant arts center it is today.

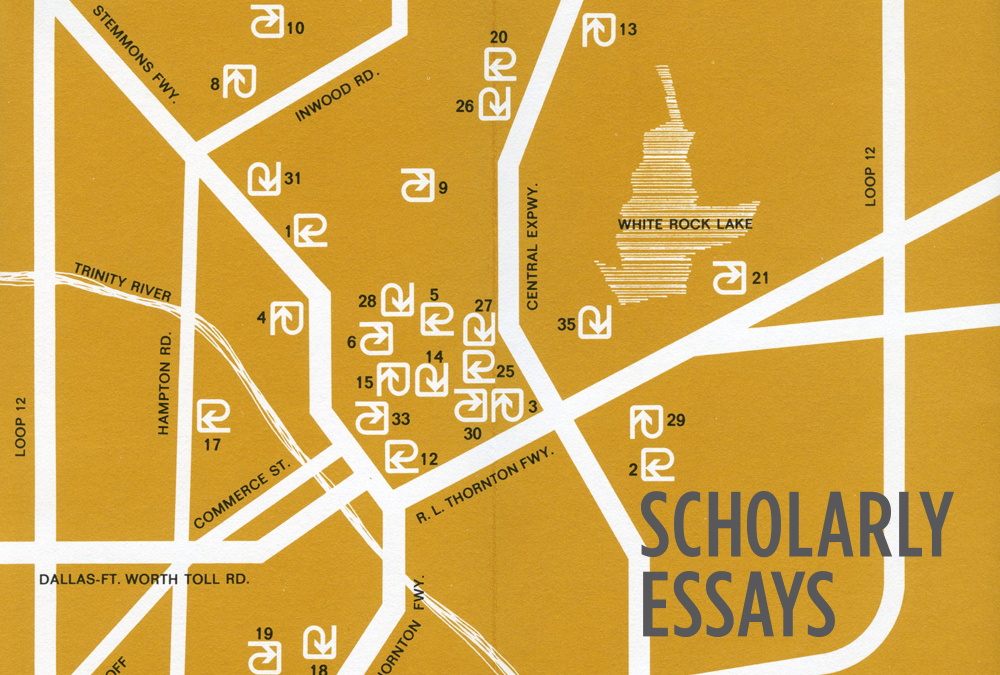

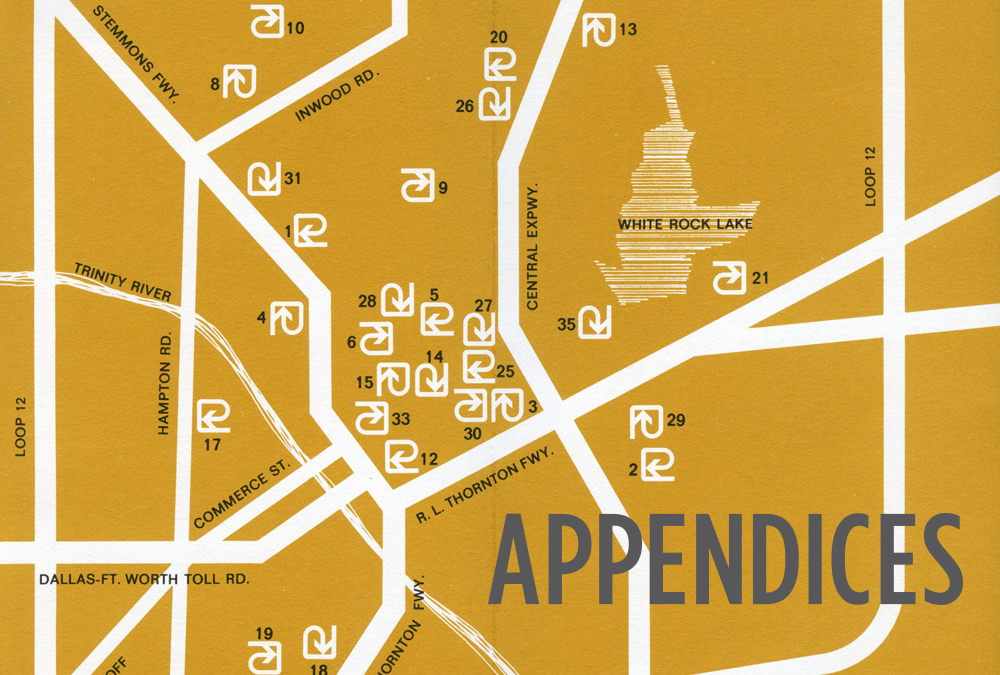

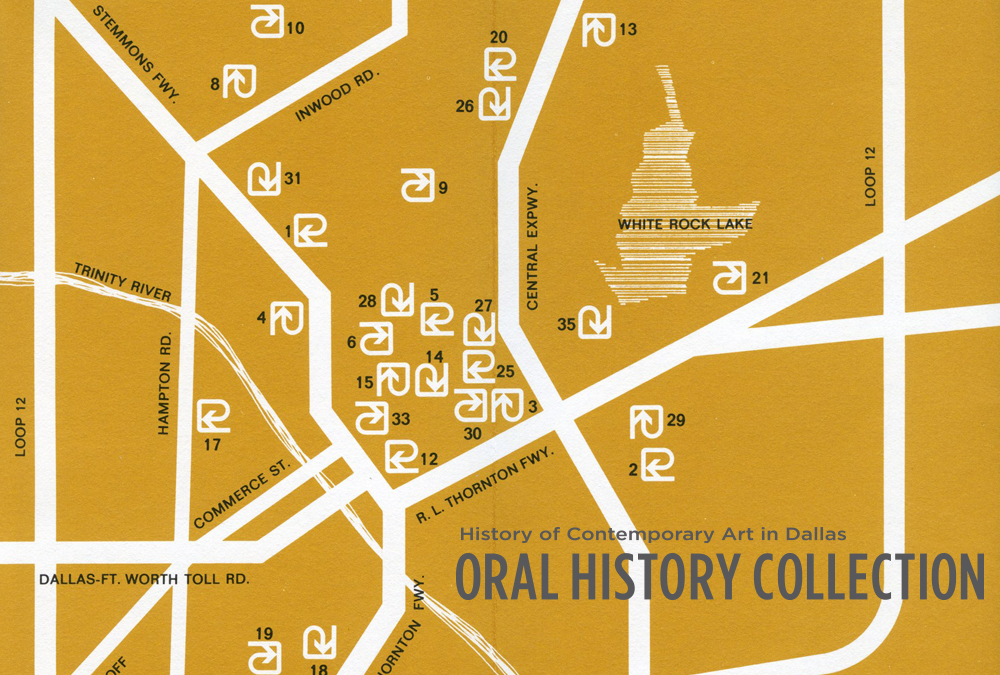

The current release includes chapter essays on the seven neighborhoods, two scholarly essays on the early history of collecting contemporary art in Dallas, an interactive gallery map documenting the history and locations of over 150 commercial galleries and nonprofit institutions in North Texas from the mid-1950s, and media-rich appendices that feature oral histories, interviews, and detailed listings of collections in the DMA Archives related to the DallasSITES research project. Future installments will include an interactive timeline and a checklist for the exhibition DallasSITES: Charting Contemporary Art, 1963 to Present, on view at the Dallas Museum of Art from May 26 to September 15, 2013.

We invite you to explore this unique online publication—the Dallas Museum of Art’s first to utilize the Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative (OSCI) Toolkit, an open-source suite of tools generously supported by the Getty Foundation and developed by the Indianapolis Museum of Art for publishing online scholarly art history catalogues.

Gabriel Ritter

The Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art

About the Texas Curatorial Fund for Research

The Texas Fund for Curatorial Research, administered by Dr. Richard Brettell, The Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair, Art and Aesthetics, at the Center for the Interdisciplinary Study of Museums (CISM), University of Texas at Dallas, was established to promote, support, and sustain advanced curatorial scholarship in North Texas. The fund, created by a gift from Nancy B. Hamon and matching research funds from the State of Texas, promotes museum-related scholarship at the highest level by supporting specific projects of local curators and art historians, often in conjunction with national and international colleagues. It offers a framework for collaboration among regional museums, universities, and other cultural institutions and between all those institutions and the larger professional world.

About the Dallas Museum of Art

Established in 1903, the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) ranks among the leading art institutions in the country and is distinguished by its innovative exhibitions and groundbreaking educational programs. At the heart of the Museum and its programs is its global collection, which encompasses more than 22,000 works and spans 5,000 years of history, representing a full range of world cultures. Located in the vibrant Arts District of downtown Dallas, the Museum welcomes more than half a million visitors annually and acts as a catalyst for community creativity, engaging people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse spectrum of programming, from exhibitions and lectures to concerts, literary events, and dramatic and dance presentations. The Dallas Museum of Art is supported in part by the generosity of DMA Partners and donors, the citizens of Dallas through the City of Dallas Office of Cultural Affairs, and the Texas Commission on the Arts.

About DallasSITES

Research for this publication and the accompanying exhibition is led by Dallas Museum of Art Research Project Coordinator Leigh Arnold as part of a three-year grant from the Texas Fund for Curatorial Research. The larger goal is to uncover, document, consolidate, and bring greater public awareness to the richly variegated yet widely underrecognized history of Dallas’s contemporary art avant-garde. Research materials will be housed in the Dallas Museum of Art Archives, creating a centralized repository for the history of contemporary art in North Texas.

This publication is best viewed using the latest version of web browser.

You may visit the links below to download and install the latest version of:

Mozilla Firefox

Google Chrome

Apple Safari

Microsoft Internet Explorer

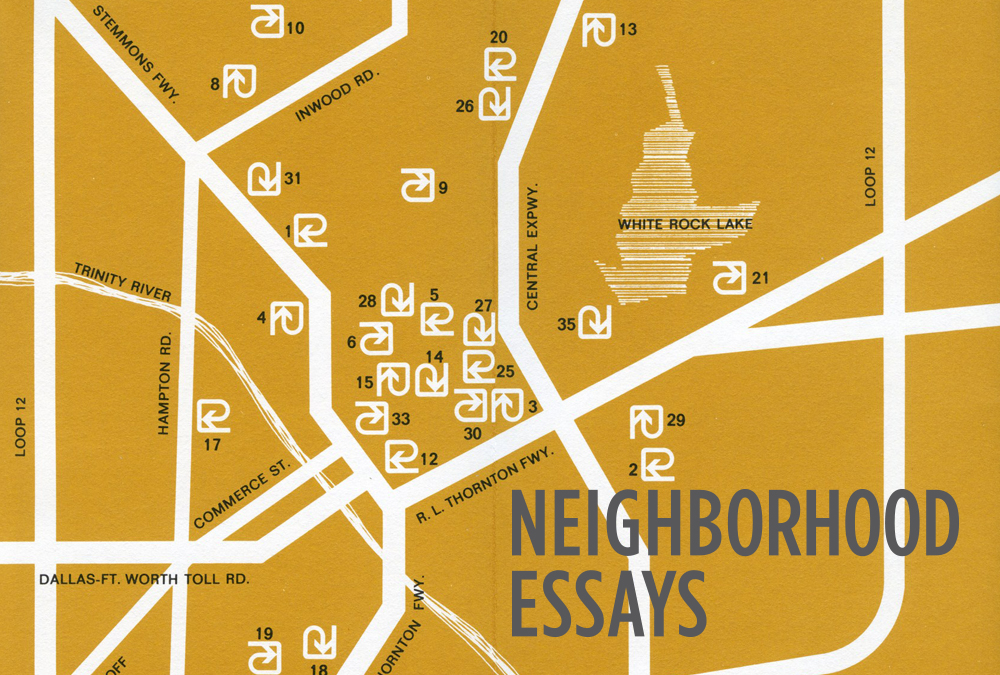

Early in the research for DallasSITES: Charting Contemporary Art in Dallas, 1963 to Present, it was apparent that the history of the North Texas art scene is also a history of the city. Dallas became a central character in the overall narrative of contemporary art in our region, told through essays on six distinct neighborhoods, with an additional essay on university communities.

Organized in chronological order, this section begins with the Fair Park–South Dallas neighborhood, which many consider to be Dallas’ original cultural district. At its peak, it was a hub of cultural activity, attracting North Texans to the museums within the state fairgrounds as well as to the artist-run spaces that developed outside Fair Park. The Dallas Museum of Fine Arts grounded the neighborhood until it moved in 1984 to the official Dallas Arts District. Since then, the South Dallas Cultural Center and the University of Texas at Dallas’ artist residency program, CentralTrak, have become the area’s cultural anchors.

Starting in the early 1960s, the neighborhood now known as Uptown was the counterpart to Fair Park–South Dallas. With the addition of the short-lived Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts in 1959, Uptown blossomed into a true gallery district, as artists and gallerists moved there to be near the museum’s action. When the DMCA merged with the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1963, many were concerned that the loss of the neighborhood’s major contemporary art institution would have a negative effect on art activity there. The opposite was true, as artists and galleries filled the gap. For the next 40 years, Uptown was Dallas’ premier gallery district, with artist-run spaces thriving alongside established commercial galleries. In 1994, the McKinney Avenue Contemporary helped ground the neighborhood by focusing on the interests of area artists with a regular exhibition program devoted to the work of regional emerging and established talent.

Across the Trinity River, the enclave of Oak Cliff has always been a hotbed of creative activity. Early on, a sense of community was evident in spaces like the Creative Arts Center of Dallas, established in 1965 in the former home and studio of Dallas-based artist Frank Reaugh. Despite (or most likely because of) a dwindling economy and overall depression in the 1960s, area artists moved to Oak Cliff and established studios. The artist collective called the Oak Cliff Four put the neighborhood on the national radar with coverage in Newsweek, Artforum, and Art in America. Over the years, Oak Cliff has been the home of artists and creative types seeking an alternative to the more polished art neighborhoods of Uptown and the Arts District. The Ice House Cultural Center was transformed into the Oak Cliff Cultural Center and continues to offer arts programming to neighborhood residents. Oak Cliff locals revel in their status as outsiders, and its artists take pride in making and doing in a part of town that recognizes and nourishes their creative talent.

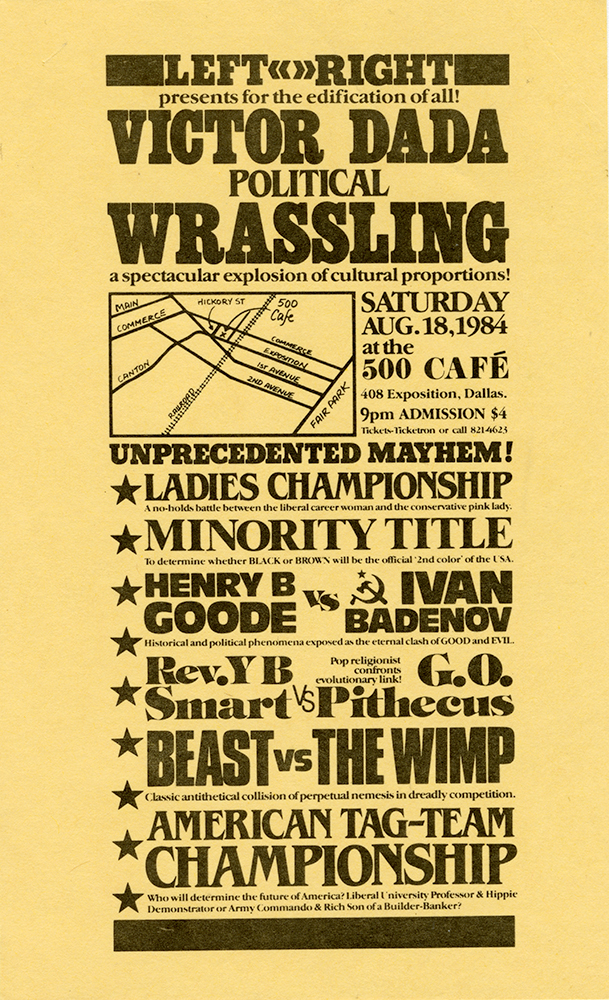

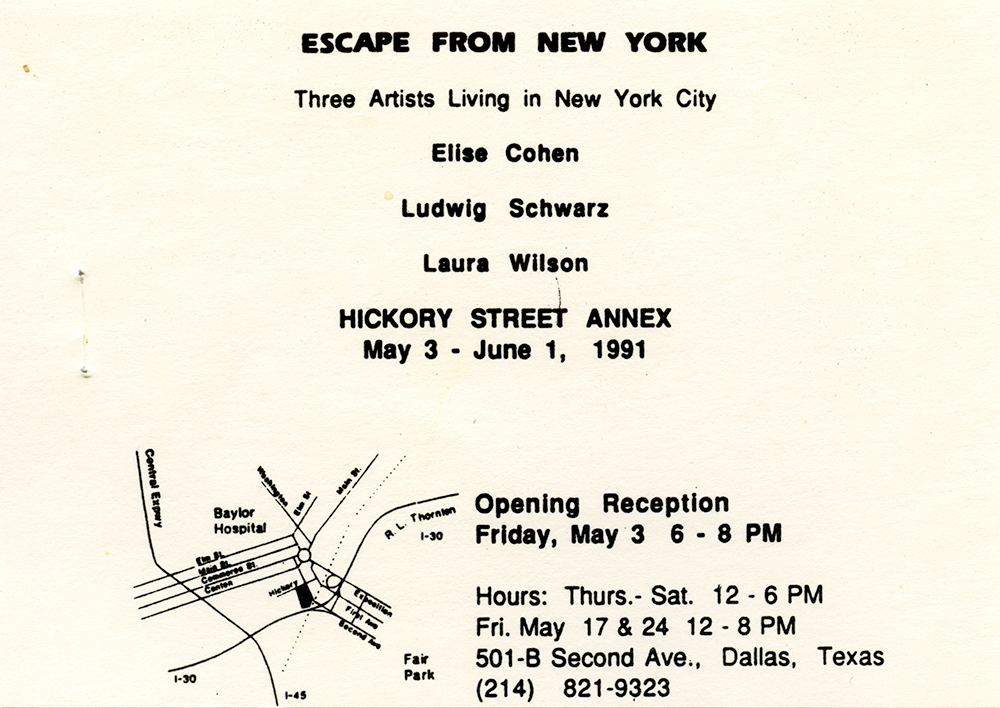

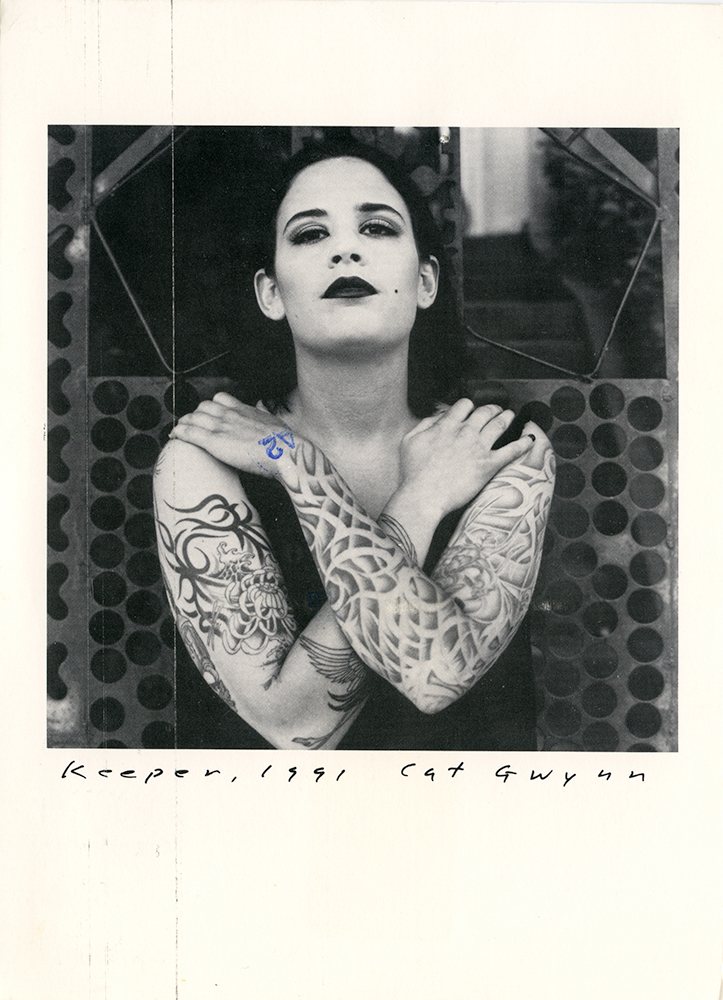

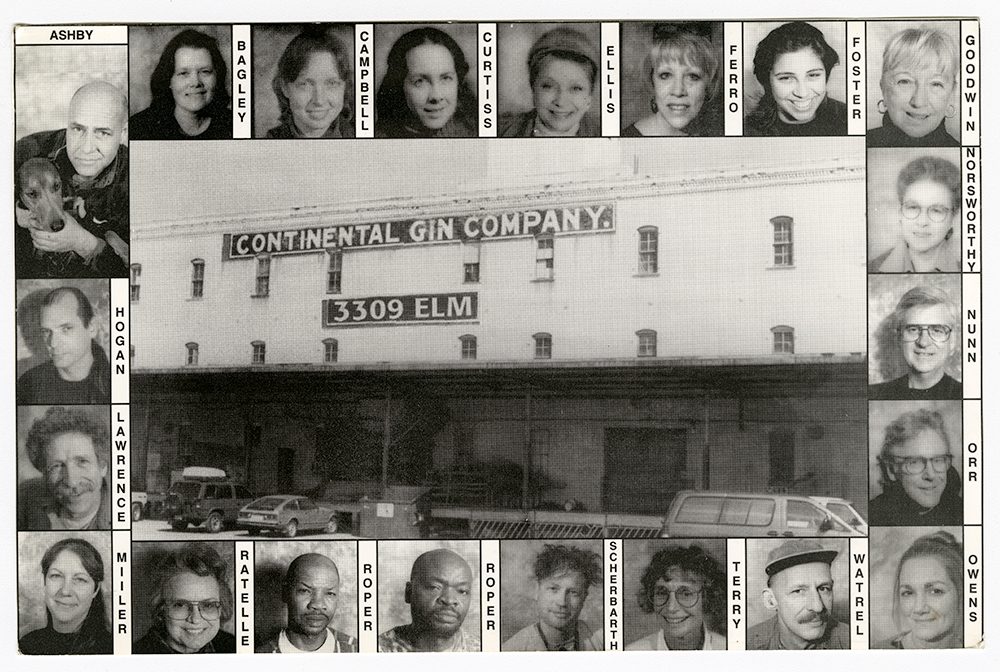

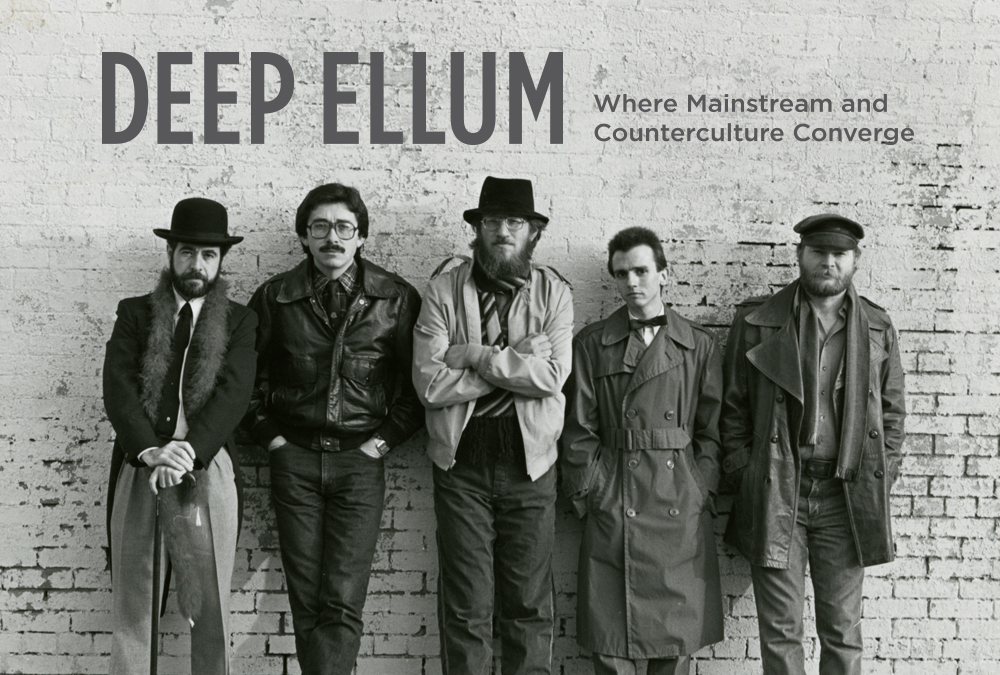

The Deep Ellum neighborhood has experienced several renaissances throughout its long history as an entertainment district. The major upswing occurred in the 1980s, when all aspects of Deep Ellum’s personality came together as a true destination for art, music, and nightlife. Galleries relocated to the neighborhood to take advantage of the raw warehouse spaces, a trend that artists had seen coming and taken advantage of for several years. Texas’ oldest artist-run space, 500X, calls Deep Ellum home and anchors the area as a place where mainstream and counterculture converge. In recent years, Deep Ellum has experienced another renaissance, with the established Barry Whistler Gallery maintaining a gallery district that welcomes spaces representing diverse options for artists and patrons.

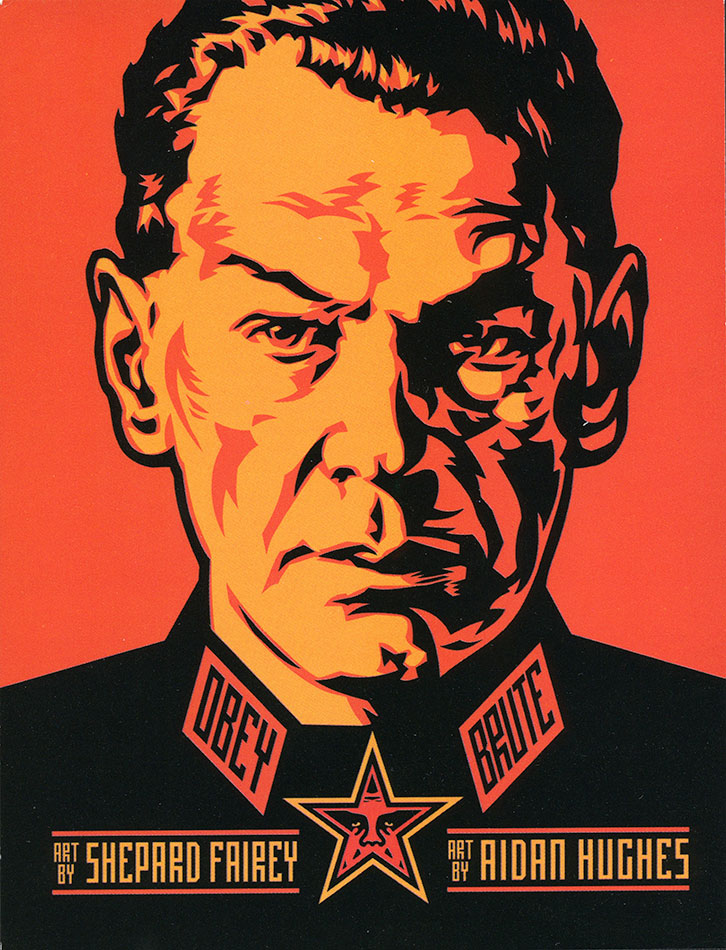

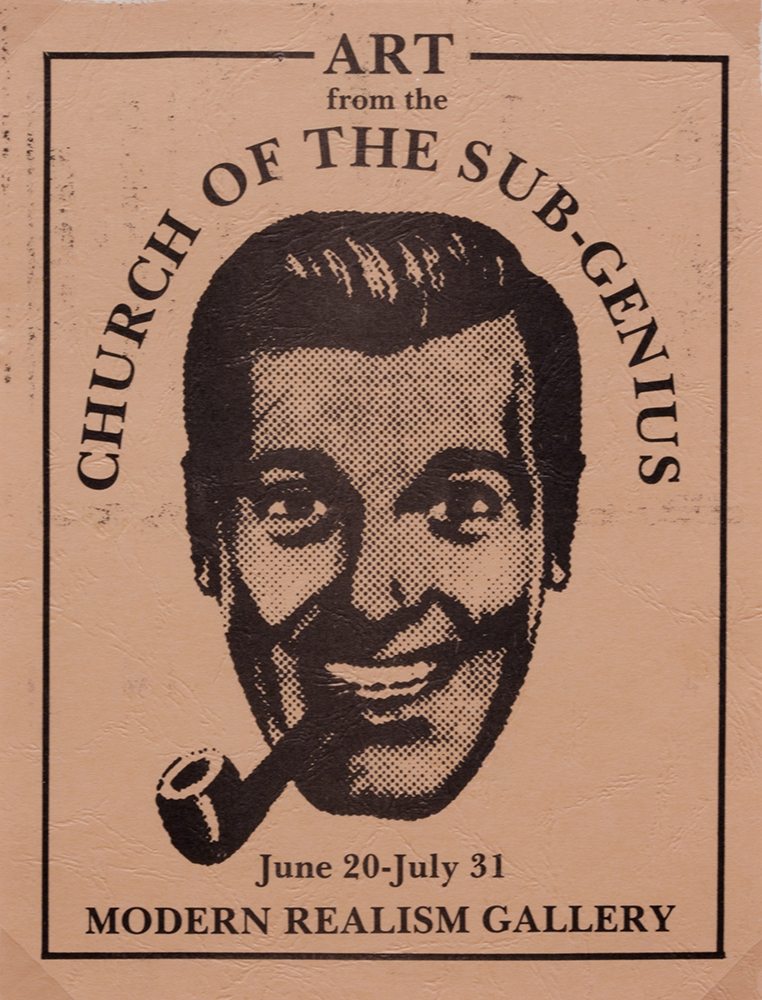

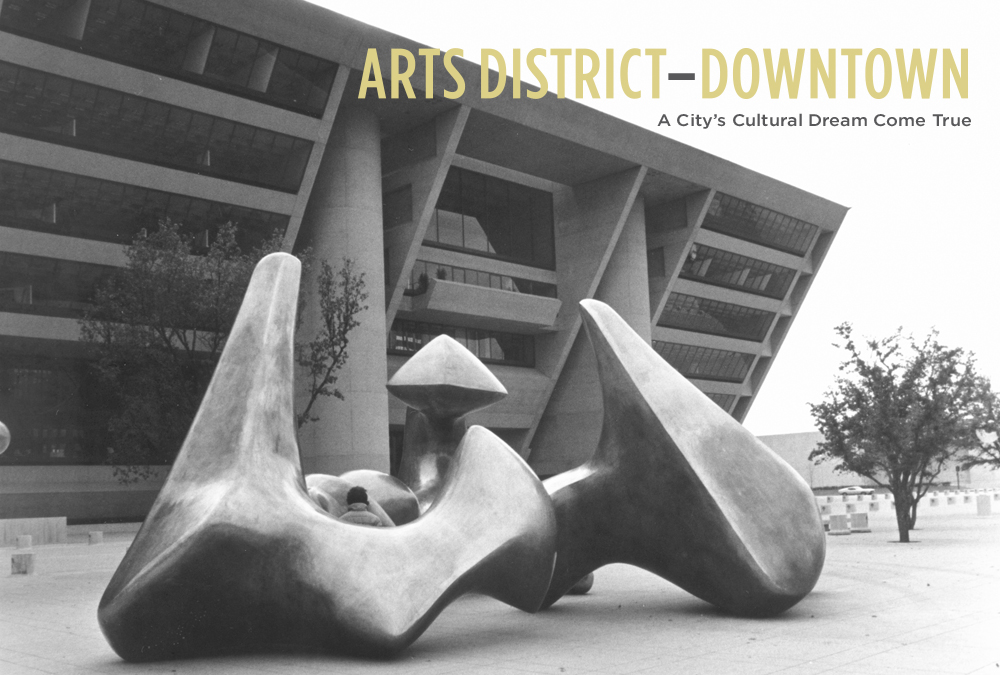

The Arts District, located in Downtown Dallas, is a city dream several decades in the making. When the Dallas Museum of Art moved to the neighborhood in 1984, the dream was born. Today it is the nation’s largest contiguous arts district, with 13 cultural institutions and organizations in a span of 19 city blocks. Outside the Arts District, culture has always thrived in Downtown. Innovative and avant-garde galleries like Modern Realism and N. No. 0 introduced local audiences to the strange and unfamiliar, with exhibitions by famed international mail artist Ray Johnson and works by legendary cult film director David Lynch. Spurred by the activity surrounding the Dallas Museum of Art and the Nasher Sculpture Center, Downtown Dallas is also home to annual events like the Dallas Art Fair and the Aurora New Media Arts exhibition.

At the turn of the 21st century, the Design District emerged as the city’s gallery district, with more than 10 contemporary art galleries or spaces. Historically a location for Dallas’ leading home designers and decorators, the neighborhood welcomed its first gallery when Nancy Whitenack’s Conduit Gallery moved there in 2002. As in nearly all of Dallas’ arts neighborhoods, low-cost available space spurred artistic development in the Design District. The addition of several new galleries and two nonprofit art spaces—the Dallas Contemporary and the Goss-Michael Foundation, both in 2010—helped the Design District shed its historical designation as a designer-decorator neighborhood.

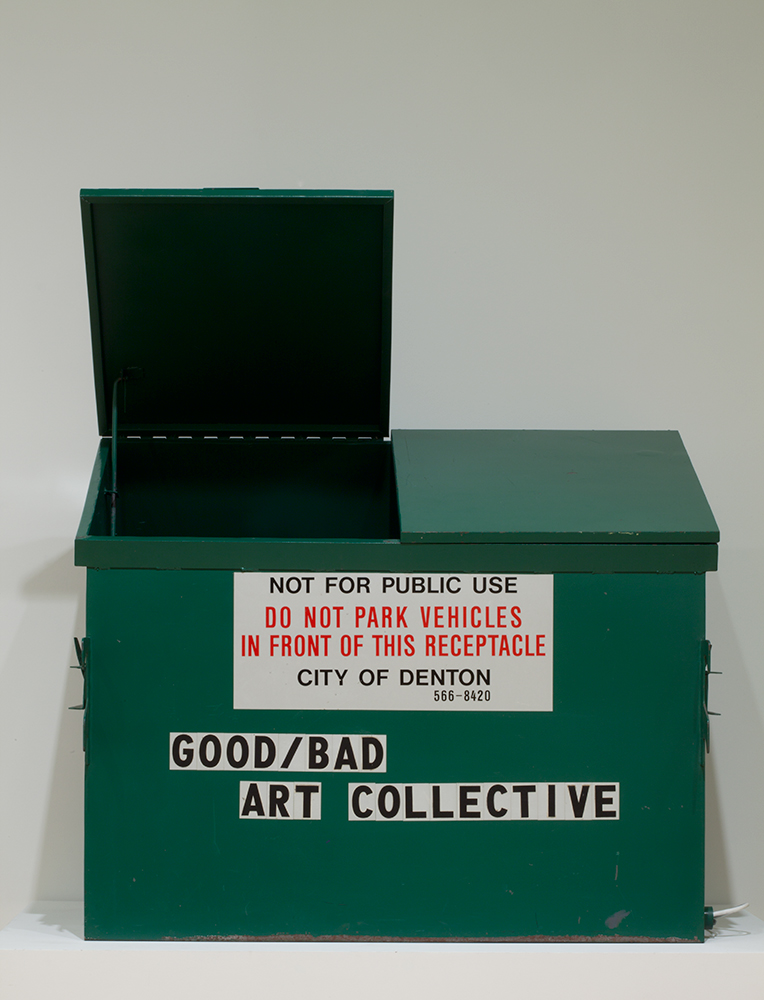

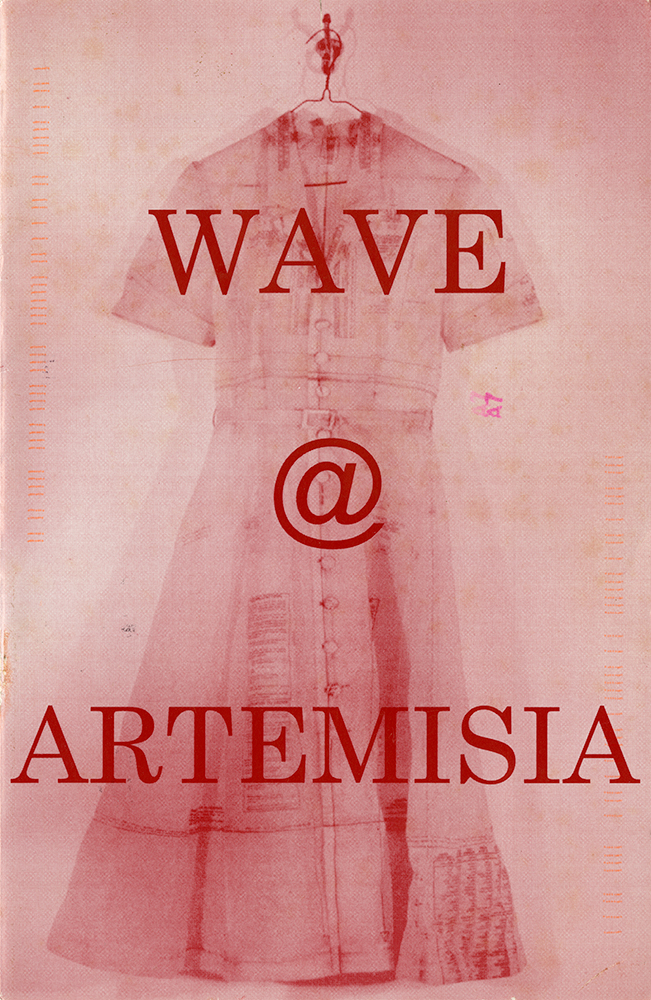

Many of the art programs in North Texas’ university communities came into their own in the 1960s and 1970s. Teaching positions have attracted artists from all over the country to live and work in North Texas, adding to the wealth of artistic resources in our region. These communities also stimulated artist collectives, most famously the University of North Texas’ Good/Bad Art Collective, active in the 1990s, but also the lesser-known all-female collective WAVE at Texas Woman’s University and the millennial Oh6 collective from the University of Texas at Dallas. Many renowned artists have visited area campuses, connecting students to national and international contemporary art practices and demonstrating what it takes to make it as a working artist. Some of Dallas’ most recognized artists are alums of North Texas programs—including David Bates, Nic Nicosia, Frances Bagley, and Erick Swenson—and the future promises to produce many more.

Leigh Arnold

Research Project Coordinator

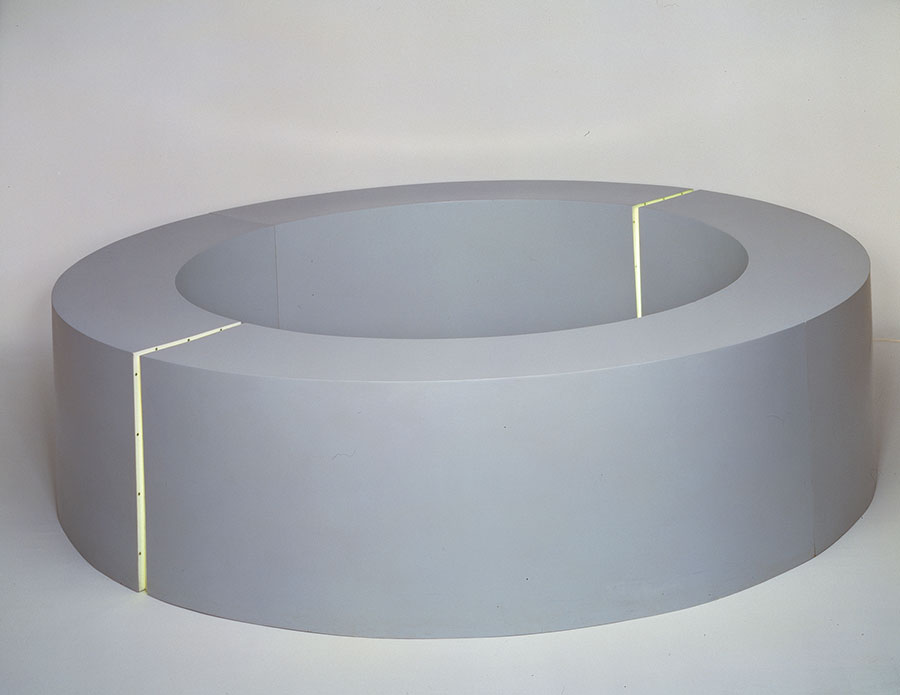

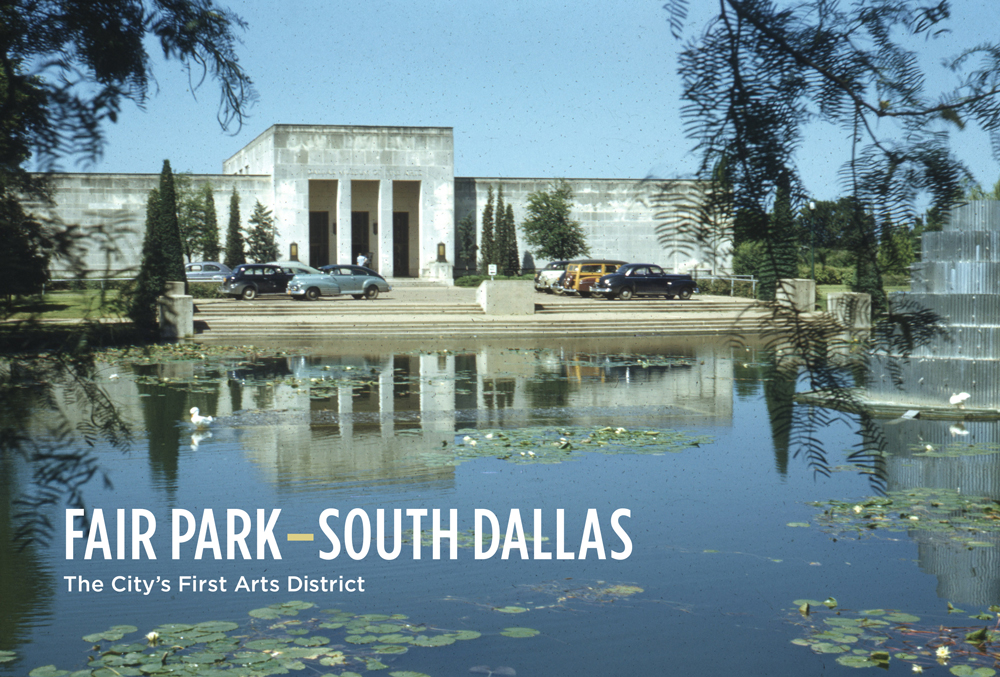

Fair Park-South Dallas: The City's First Arts District

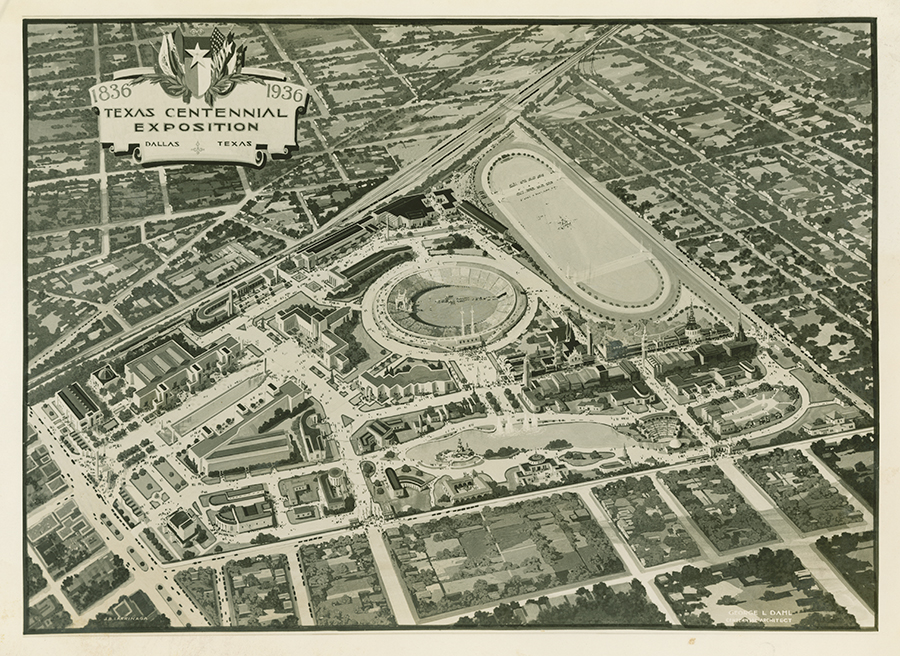

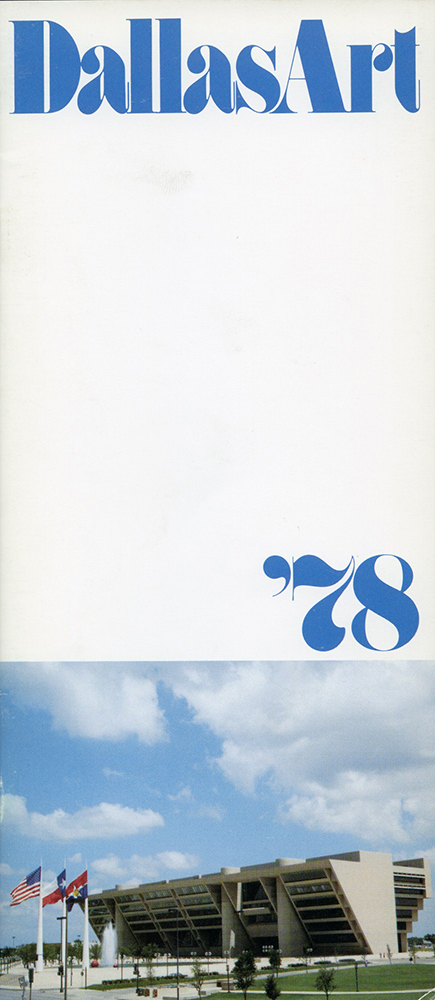

The history of contemporary art in Dallas has its roots in the Fair Park–South Dallas neighborhood, the city’s first arts district and a lively destination for art and culture. From the mid-1930s this area was home to North Texas’ finest cultural institutions, innovative galleries and alternative spaces, and a thriving community of artists. In a bid for the State Centennial Celebration in 1936, the City of Dallas expanded and beautified the county fairgrounds in South Dallas. Practically overnight, the city gained more than 200 acres of parks and dozens of art deco–style buildings, completed in time to host the event (Fig. 1). As part of the Fair Park expansion, permanent buildings were added to the grounds for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and the Dallas Art Association, governing body of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (DMFA) (Fig. 2). The Dallas Art Institute opened in the DMFA’s new building in 1938. In 1941, the official Museum School was established under the leadership of Museum director Richard Foster Howard, employing some of the state’s most recognizable artists as professors and offering classes in lithography, drawing, sculpture, ceramics, painting, and life drawing. The concentration of art and culture in Fair Park spilled into the surrounding neighborhood, attracting artists to live and work near the city’s cultural hub.

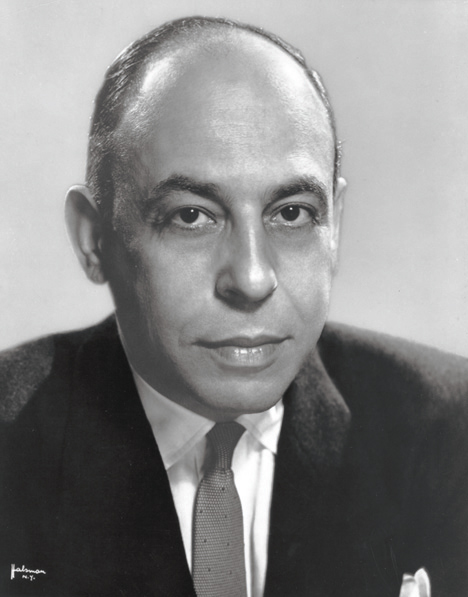

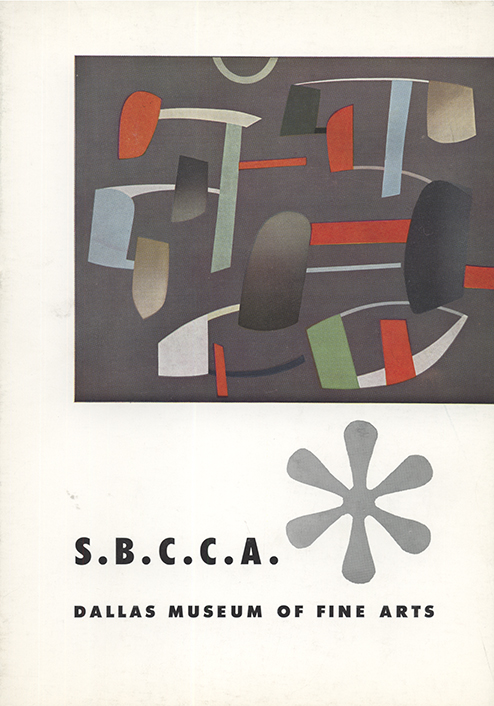

At its new home in Fair Park, the DMFA wasted no time in introducing the public to fine art. From the early 1940s through the 1960s, the Museum’s collecting and exhibitions reflected the interests of Jerry Bywaters, director beginning in 1943. Major exhibitions focused on Latin American contemporary art and local and regional art. Some exhibitions, including the landmark photography show The Family of Man and Some Businessmen Collect Contemporary Art, generated controversy in conservative McCarthy-era Dallas.

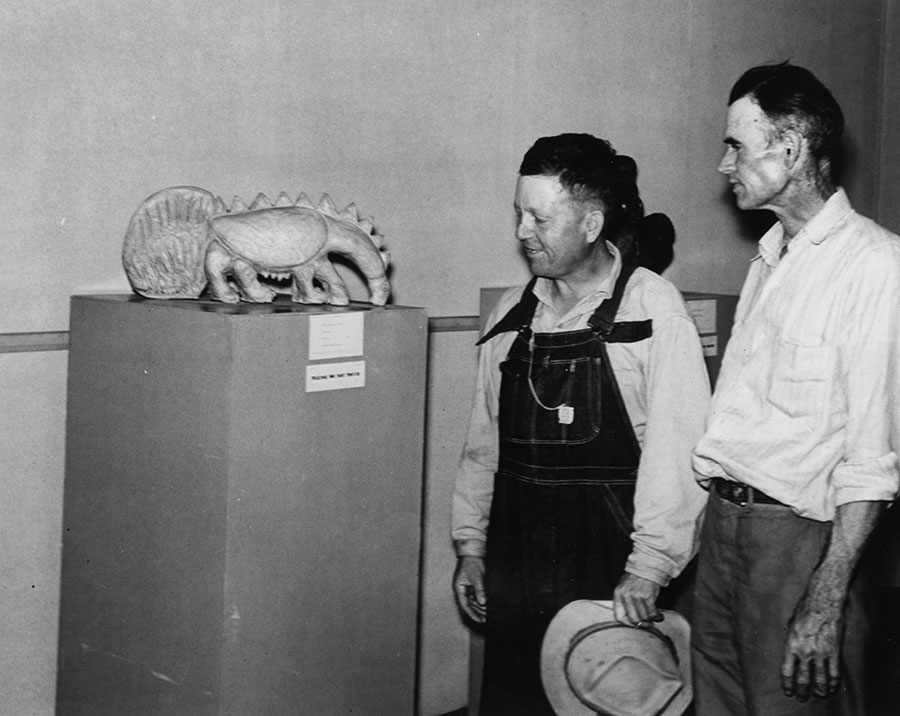

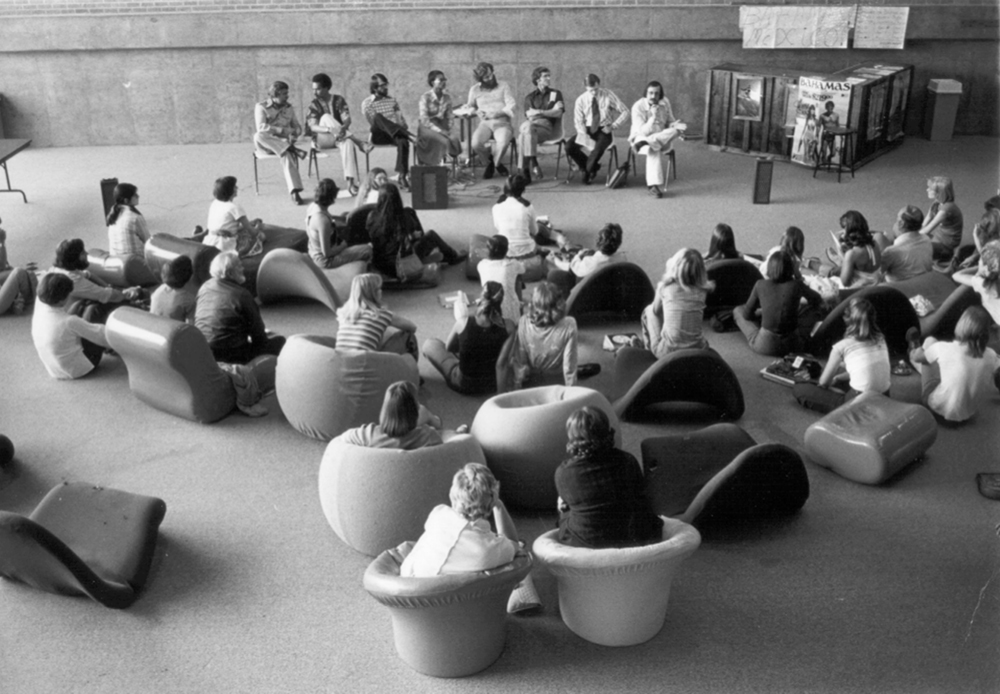

During peak periods, Fair Park was abuzz with activity, hosting stock shows, rodeos, horse racing, concerts, and football games. Attracting visitors was simply a matter of opening the Museum’s doors and advertising within the park, as events there helped increase attendance. Museum visitors were a diverse mix of area farmers, society women, and schoolchildren (Fig. 3), and the Museum did its best to accommodate its audience by gearing programming toward these groups. With the establishment of the Museum League in 1938, concerts, printmaking programs, children’s tours, and radio programs became a regular part of the DMFA, and in the early 1970s, members of The Assemblage, a young art collectors’ group, hosted Cowboy Brunches at the Museum before Dallas Cowboys football games to encourage the public to visit.

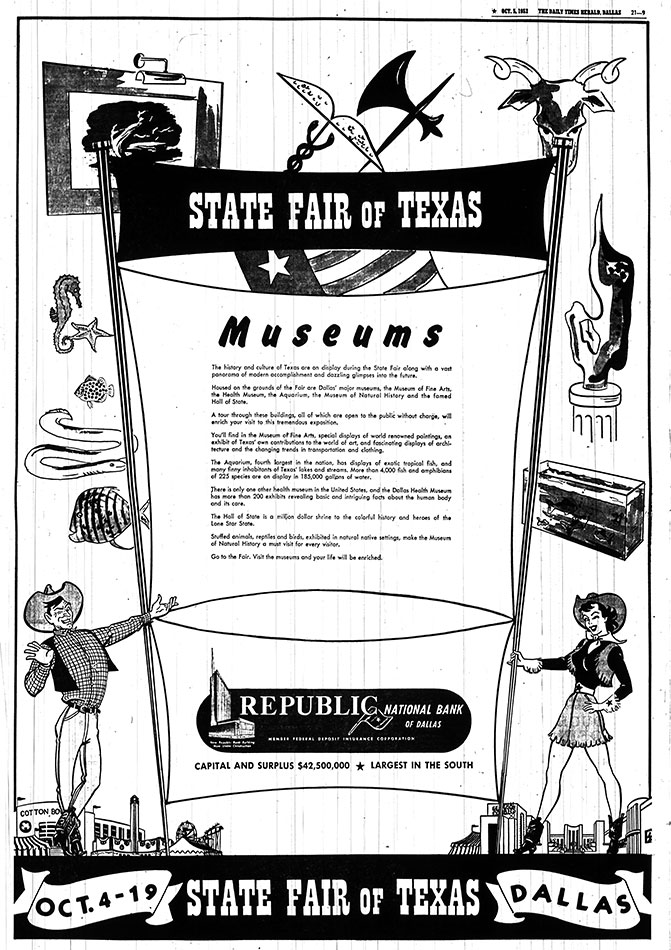

The most exciting time of year in Fair Park was the annual State Fair of Texas (Fig. 4). During the month-long celebration, hundreds of thousands of people would see the work of artists from all over the state in juried competitions like the Texas Annual Painting and Sculpture exhibition. Hosted by the DMFA and considered an accurate survey of the arts in Texas, these exhibitions emerged as early as 1928 with the First Allied Arts Exhibition of Dallas County. By the 1940s, the Texas General and the Southwestern Prints and Drawings exhibitions had been established. These competitive shows helped artists advance their careers through the validation that came from internationally recognized jurors. They also enabled the Museum to expand its collections by acquiring many of the prizewinning works.

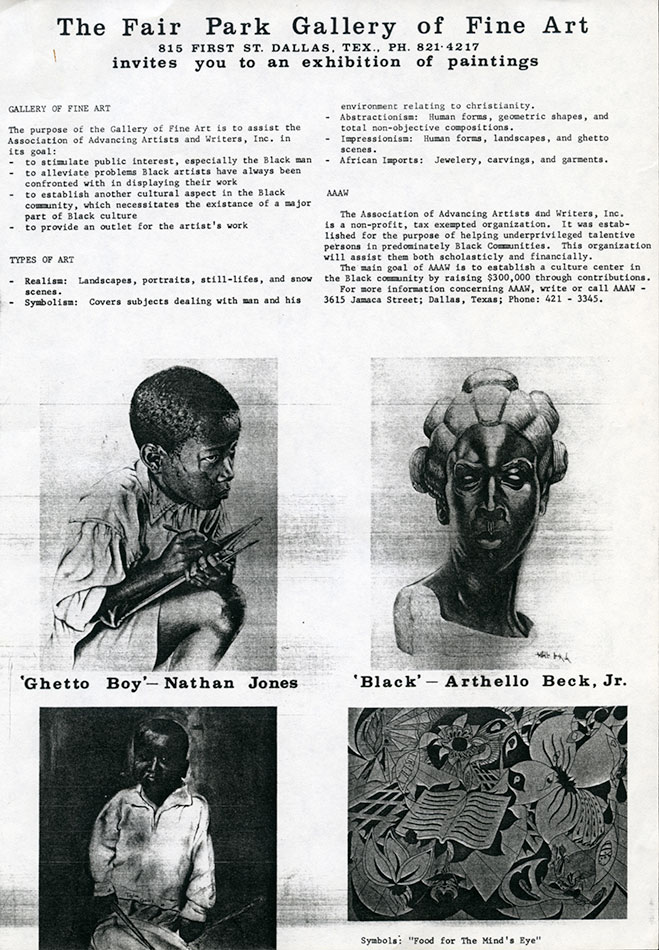

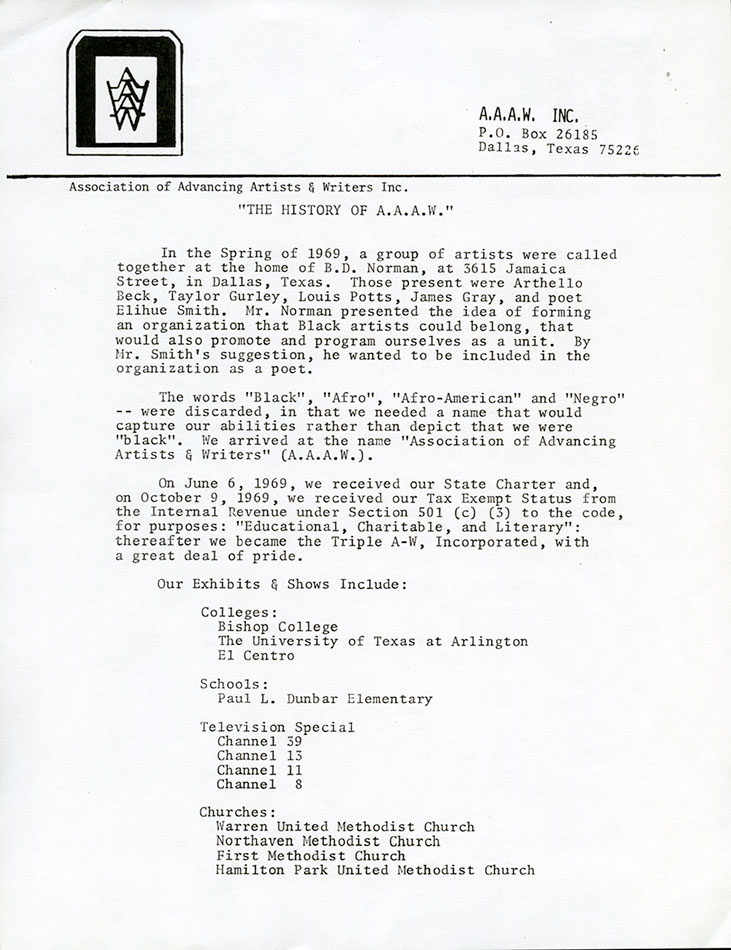

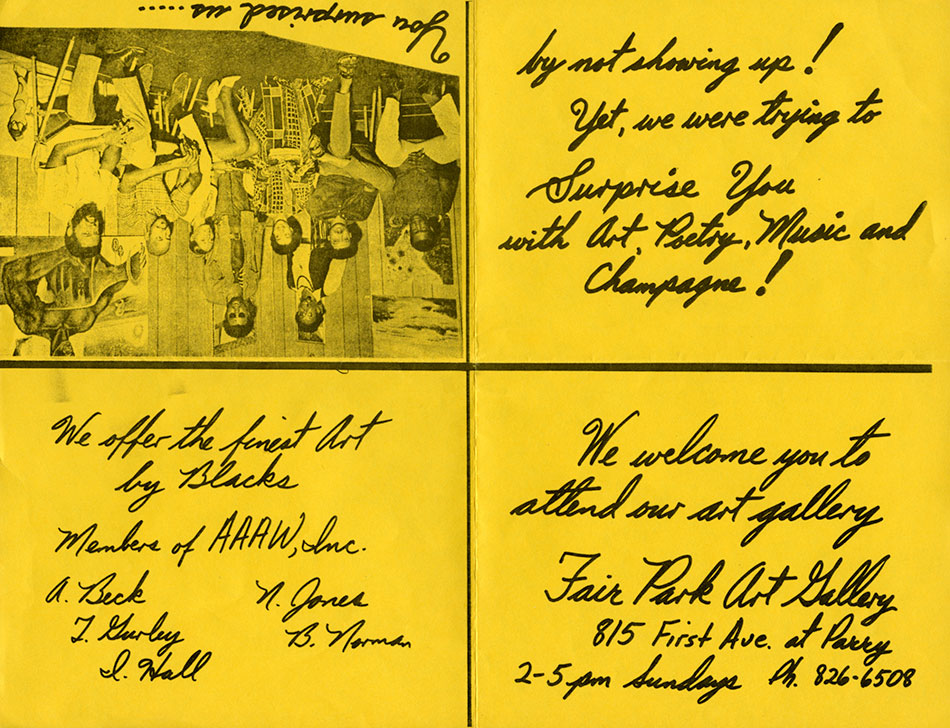

Arts activity in South Dallas was not limited to Fair Park. By the early 1970s, artists began moving into buildings facing the Music Hall at 909 First Avenue, renovating raw warehouses and vacant homes into live-work studios, alternative galleries, and cooperative spaces. Artists Arthello Beck and Nathan Jones were among the first, opening the Fair Park Gallery of Fine Art in a small house at 815 First Avenue in 1970 (Fig. 5). The gallery was the bricks-and-mortar location for the Association of Advancing Artists and Writers, Inc. (AAAW), an artist-run organization formed in the spring of 1969 to promote the work of African-American artists and writers. The founding members included visual artists Bobby D. Norman, Taylor Gurley, Louis Ray Potts, and James Gray and poet Elihue Smith. “We organized the AAAW in 1969 out of frustration which confronted black artists in their efforts to exhibit their work,” Norman explained. “After we got organized, poets and designers, and musicians and dancers all wanted to be in on it.”

Exhibiting opportunities for African-American artists in Dallas at the time were few and far between. An organization like the AAAW was crucial to encouraging and supporting these artists as they struggled to have their work shown in the still racially divided city. There were only a few local galleries, and they had rosters of predominantly white artists and were located in the historically white neighborhoods of Uptown and North Dallas. The problem of gallery representation persists to this day and goes beyond the lopsided gallery-to-artist ratio. As artist Vicki Meek explains, "African-American artists find themselves in a Catch-22 situation: If they are doing work that in any way expresses their ethnicity, they have placed themselves outside the mainstream. And what ‘mainstream' really means is ‘white, male art.’ Then you've got the other side, in that you don't have a strong black buying public. . . . There are few people on the black side who are willing to put the time and effort into it.”

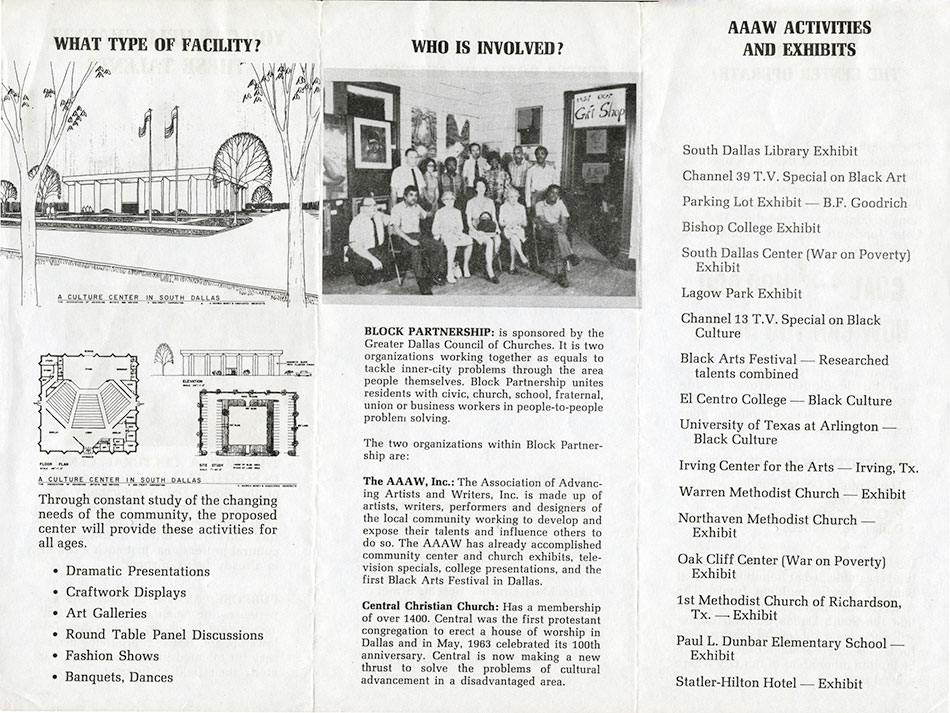

The AAAW staged exhibitions at Bishop College, the University of Texas at Arlington, El Centro Community College, and churches in the South Dallas and Oak Cliff neighborhoods (Fig. 6). The opening of the Fair Park Gallery in 1970 gave the expanding membership a permanent space to work and to exhibit performance, written, and visual art (Fig. 7).

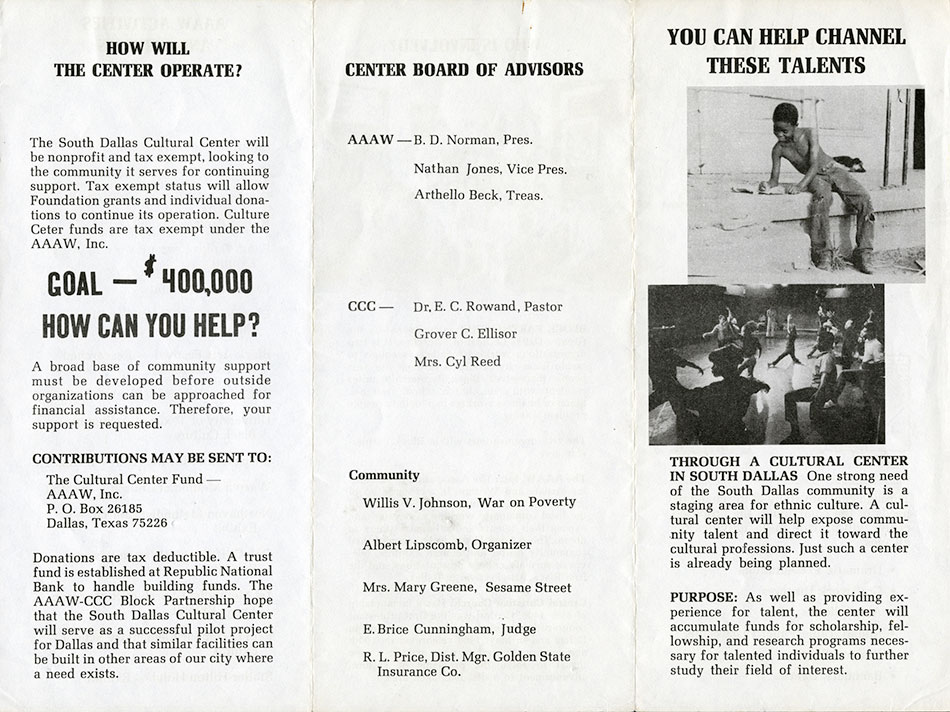

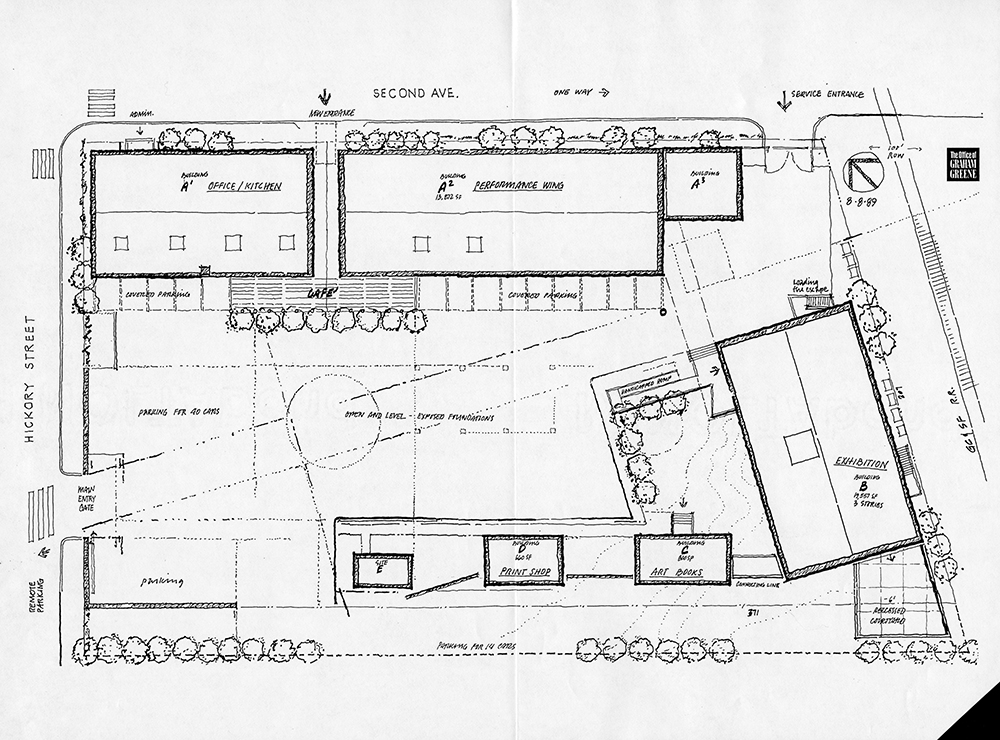

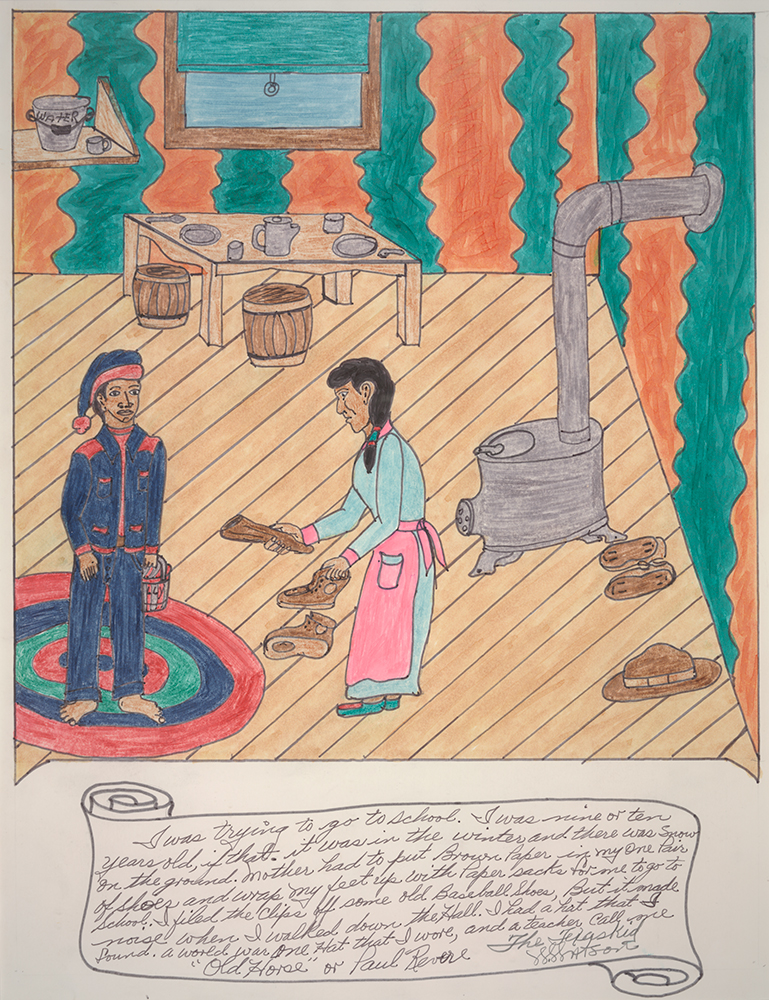

The AAAW also had a larger goal: establishing a cultural center in South Dallas that would broaden the exposure of African-American artists, writers, performers, and musicians. In 1971, the organization hosted a Black Arts Festival at the Fair Park Gallery as the first fundraiser for the proposed cultural center. Architect A. Warren Morey drew up plans, and for the next decade and a half, advocates continued to raise funds and awareness (Fig. 8, Fig. 9). But by the time the South Dallas Cultural Center opened in 1986, the AAAW had dissolved as a group.

In 1972, just down the street from the Fair Park Gallery, artists Richard Childers and David McCullough moved into a block of buildings at 842 First Avenue. Small businesses, bars, and restaurants occupied the street-level spaces, while the vacant second-level lofts offered thousands of available square feet (Fig. 10). Rent was low because the lofts usually had no modern amenities, so the artists had to install kitchen appliances, toilets, showers, air conditioning, and heating. But what these spaces lacked in comfort, they made up for in size and natural light.

Once Childers and McCullough completed the renovations in their space, more artists moved in to take advantage of the clean, well-lit galleries and live-work lofts. Known briefly as the 842 Collective, artists Gary Brotmeyer of New Orleans, Robin David of Atlanta, and Lanie Luckadeo and Andy Parks of Dallas, together with Childers and McCullough, worked in varying media and practiced transcendental meditation together as a way to move beyond individual egos and promote a spirit of collaboration. The 842s organized exhibitions that showcased their talents—including sculpture, performance, painting, and music—in their gallery, known as the AUM Gallery (Fig. 11). As the city’s first true alternative space, AUM filled a void in the Dallas art scene, as there were few exhibiting options available to artists not represented by commercial galleries.

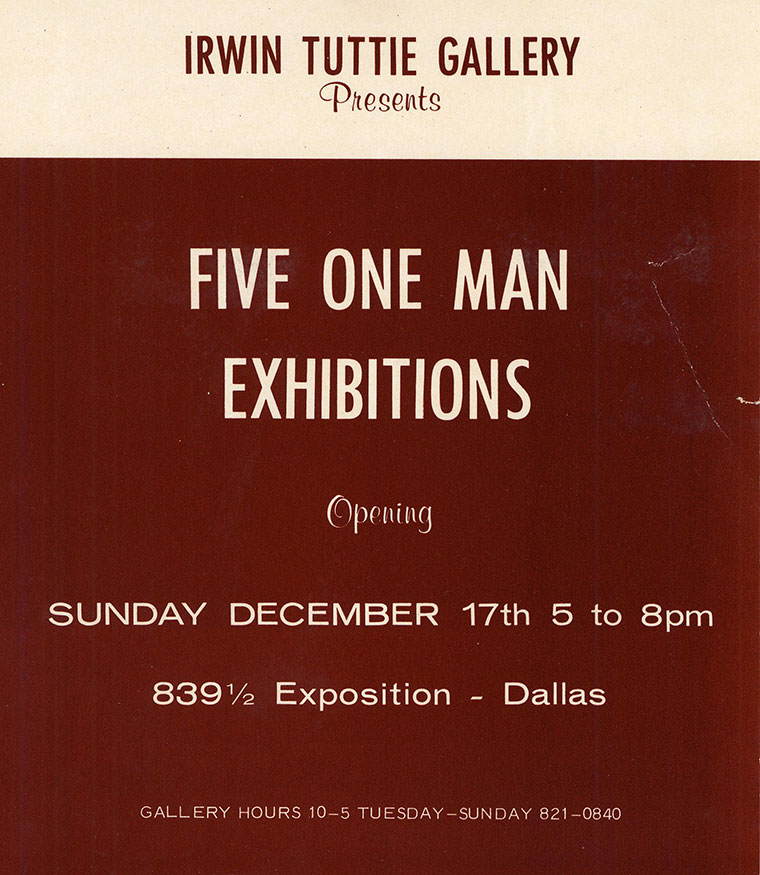

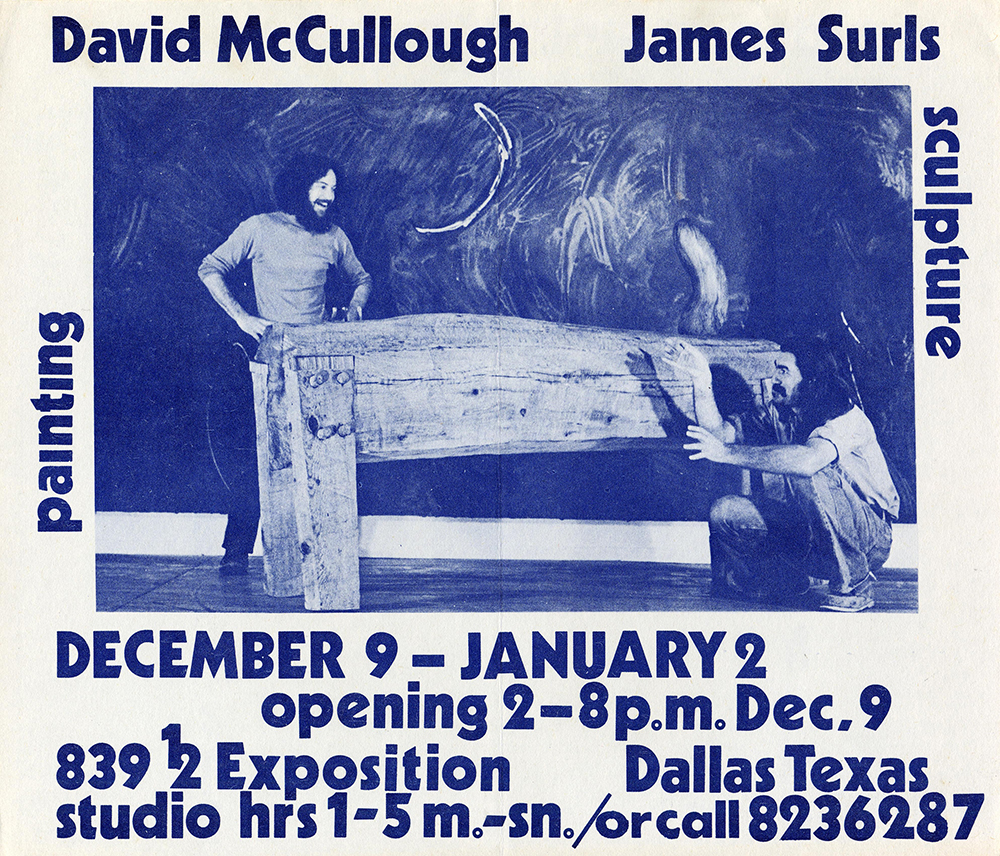

Before long, the energy surrounding the 842s spread to other local artists who were interested in developing alternative spaces of their own. For a short time, New York painter Irwin Tuttie lived in the second level at the corner of 839 1/2 Exposition Avenue, creating a space that operated more like a commercial gallery featuring exhibitions of local and regional artists (Fig. 12). Tuttie’s short-lived space was soon taken over when David McCullough decided to expand his own loft. McCullough renamed the location Oura, Inc., and with Dallas gallerist Ruth Wiseman, he launched a venue to stage exhibitions of his work and that of other emerging artists, notably James Surls (Fig. 13).

Individual artists like George Goodenow, Alberto Collie, and Mac Whitney also had studios in the neighborhood, adding to the energy and activity in South Dallas in the 1970s. As a response to this burgeoning artists’ community, Richard Childers, with artists Gilda Pervin and Stephen Grant, organized First Saturday Art in December 1975. On the first Saturday of every month, artists paid a small fee to exhibit in the loft space of 842 First Avenue. They were allowed to sell directly to the public, sidestepping commercial galleries and art dealers. First Saturday Art, Childers explained, was “an open opportunity for professional artists to show their works that will create overall high-quality exhibits and stimulate greater production and appreciation for the arts in Dallas.”

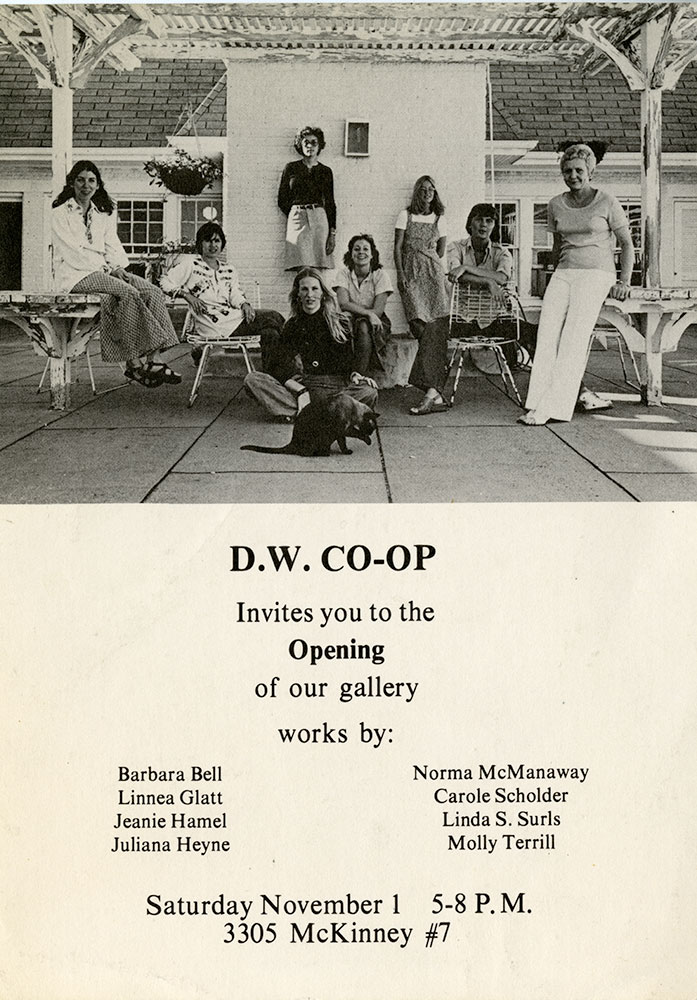

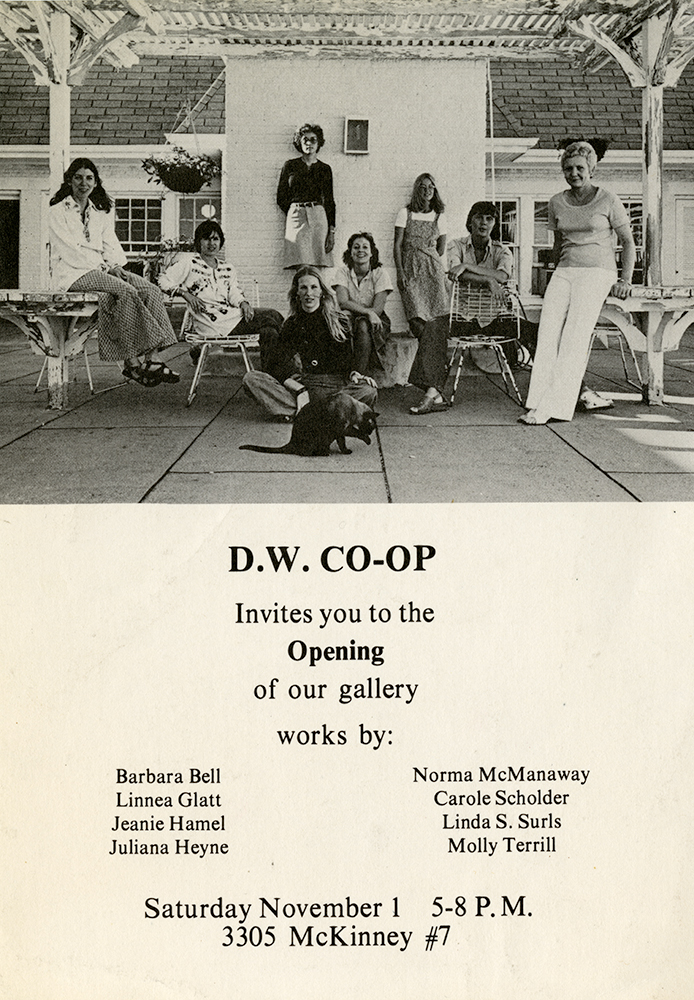

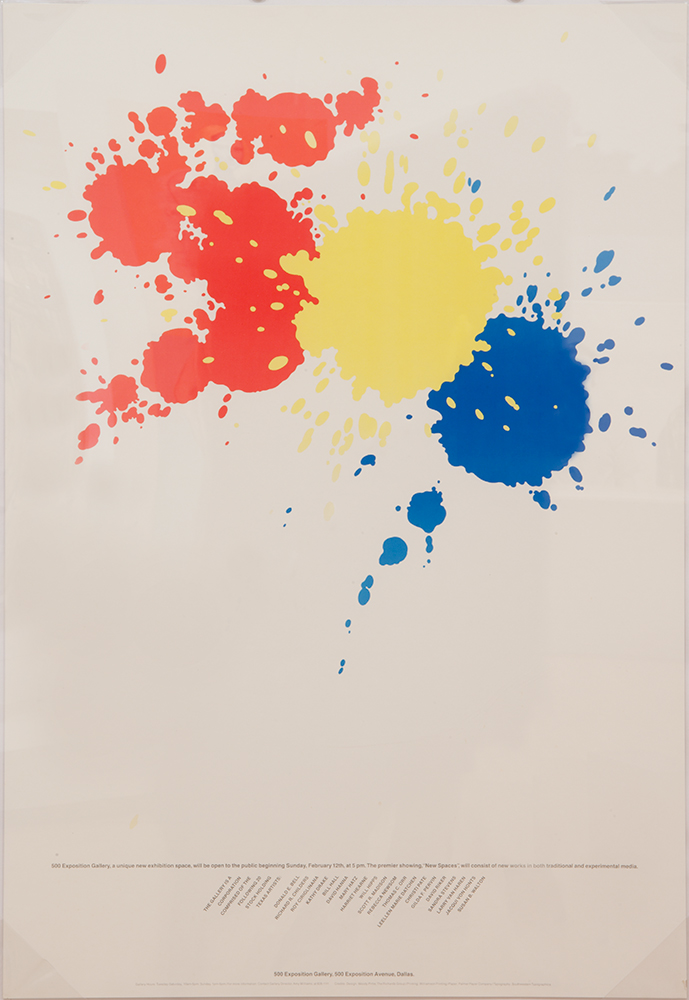

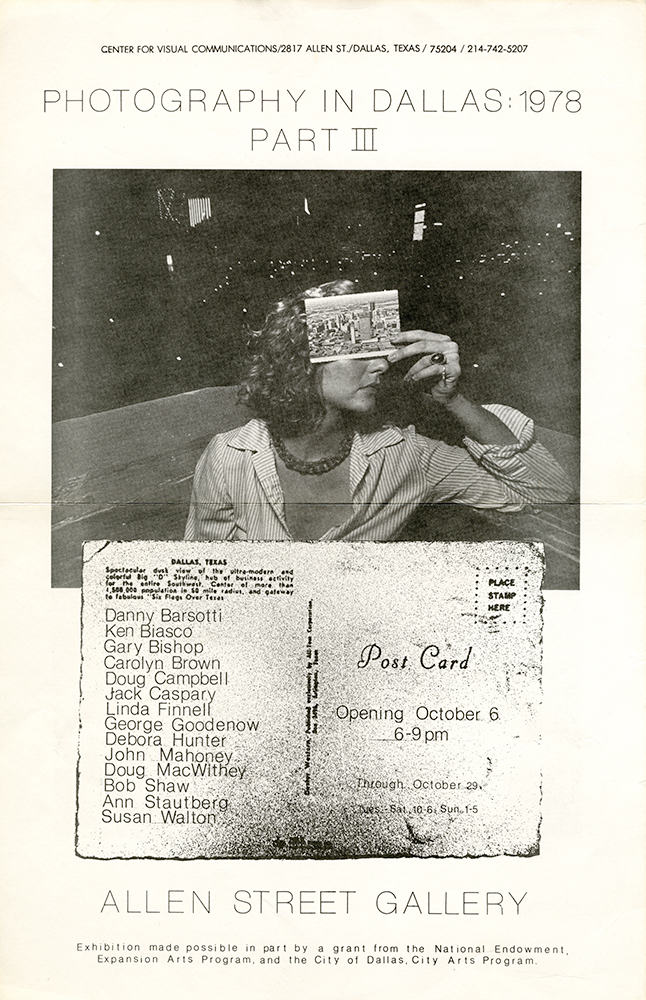

Exhibiting options in Dallas were limited when Childers introduced his concept. The DMFA had discontinued the annual juried competitions in 1976, and while a few local galleries, like Delahunty and Atelier Chapman Kelley, gave exhibitions to area artists, the art scene was still relatively small. Artists were taking opportunities into their own hands, and the popularity of the artist-run space continued to spread through other parts of town. Third Sunday, likely an inspiration for Childers’ First Saturday events, debuted in 1975 and enjoyed continued success in giving local photographers the opportunity to exhibit their work and sell directly to the public. A group of photographers interested in a venue dedicated to the promotion and display of photography organized the Allen Street Gallery in the Uptown neighborhood in 1975. Also in Uptown, eight artists established the Dallas Women’s Co-op (DW Co-op, later DW Gallery) in 1975 as an artist-run commercial gallery (Fig. 14). Rounding out this trend, Richard Childers and Will Hipps established what is now Texas’ oldest artist-run space when they purchased and renovated an old tire warehouse into a gallery/studio space. The 500 Exposition Gallery (later shortened to 500X) was established in 1978 on the far edge of Deep Ellum, just under the freeway from Childers’ longtime residence on First Avenue across from Fair Park.

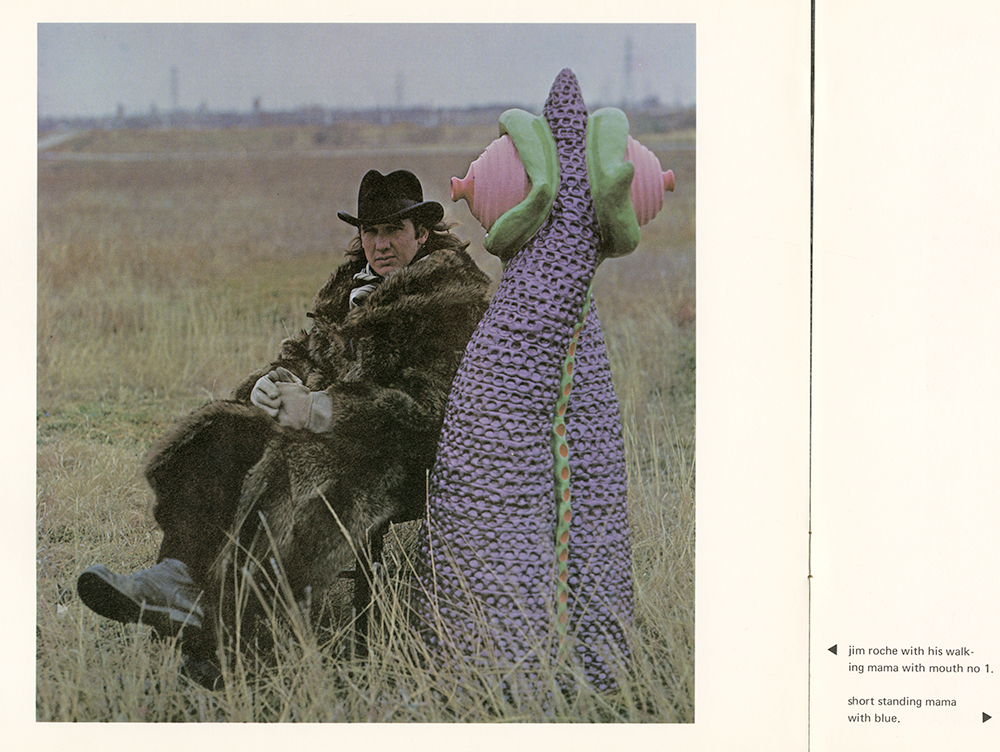

As local artists developed an active arts community outside the boundaries of Fair Park, DMFA director Merrill Rueppel and curator of contemporary art Robert Murdock worked together to develop the Museum’s contemporary collection by acquiring masterpieces by international artists while maintaining connections to the local Dallas base. Shortly after his appointment in 1970, Murdock organized the exhibition Interchange with the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (Fig. 15). Three Dallas artists—George T. Green, Sam Gummelt, and Jim Roche—were paired with three Minnesota artists—Jerry Kielkopf, Jerry Ott, and Carl Brodie—to “provide opportunities for a decentralization of New York and Los Angeles art production and enable artists from different regions to exchange ideas” (Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18).

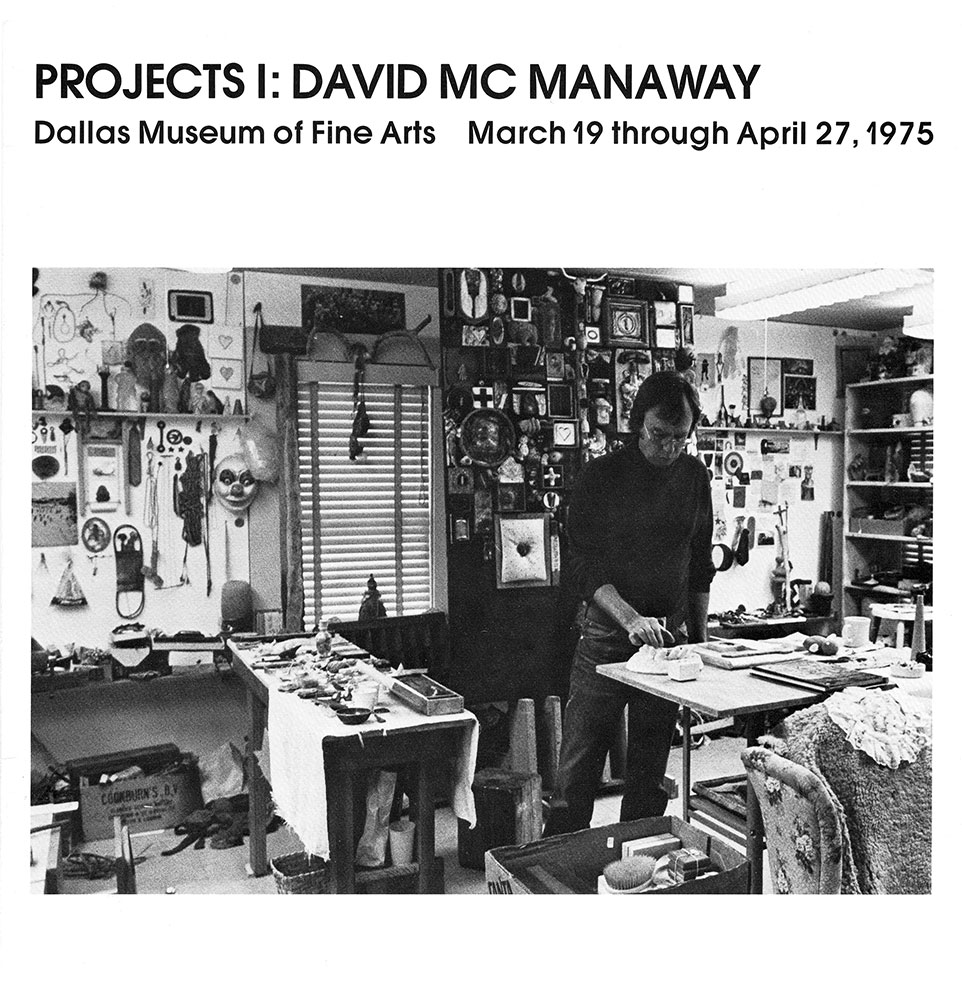

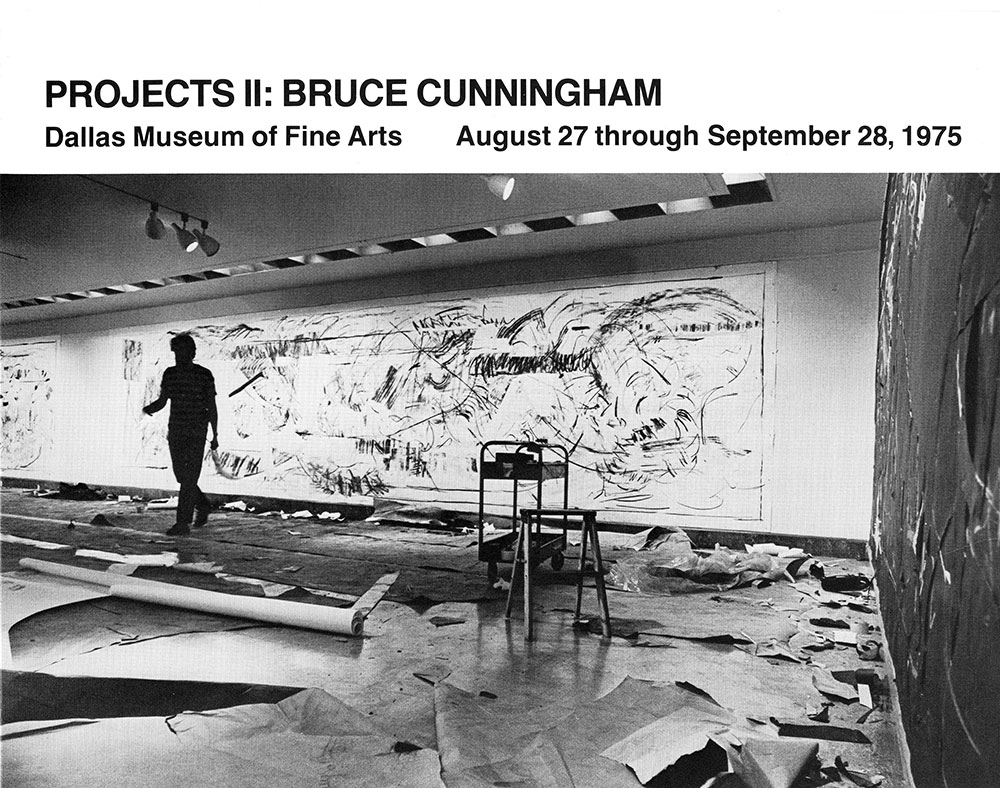

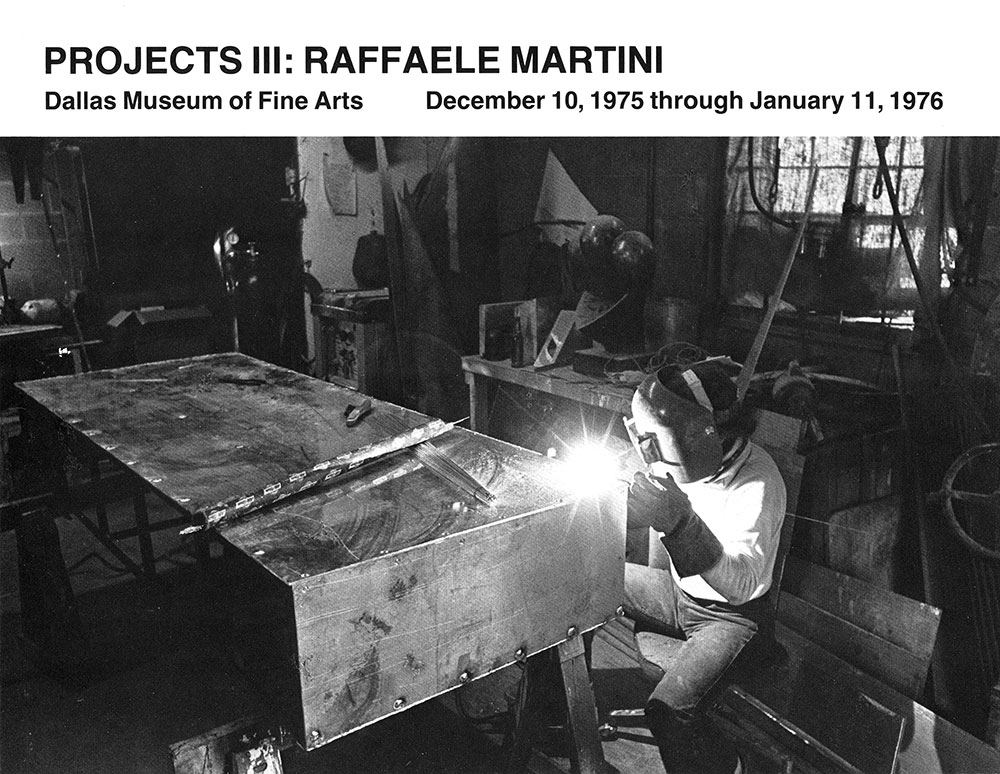

Following a run of major museum exhibitions like the Pablo Picasso exhibition of 1967 and retrospectives of Mark Tobey (1968), Franz Kline (1968), David Smith (1969), and Richard Tuttle (1971), Murdock inaugurated a series of small exhibitions titled Projects. The idea was to give an individual artist the opportunity to transfer his or her studio practice to the DMFA galleries. Whether or not Murdock intended it, the short-lived series featured three artists who lived and worked in Dallas: David McManaway, Bruce Cunningham, and Raffaele Martini (Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Fig. 21).

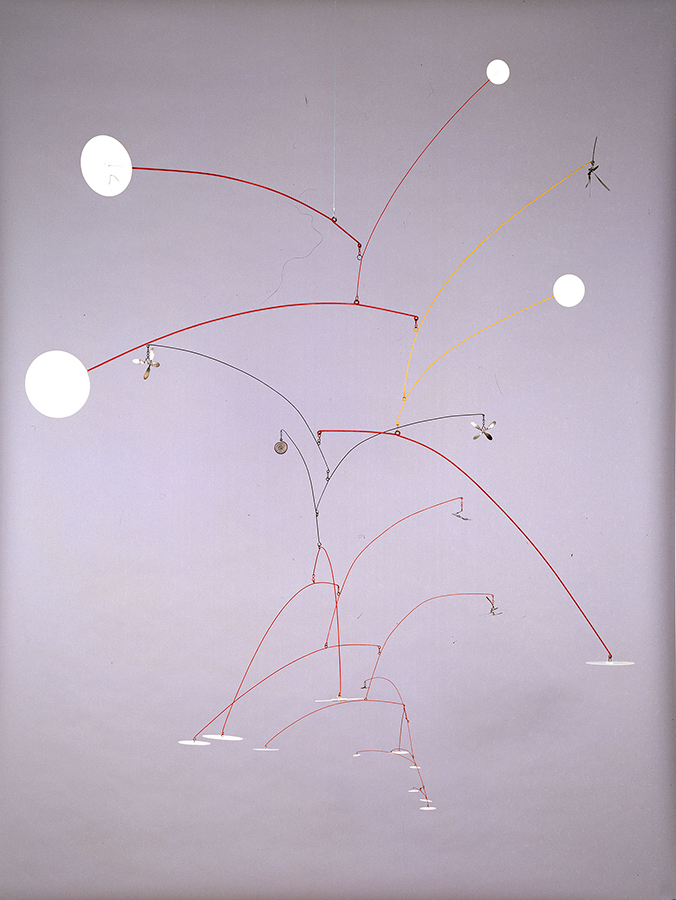

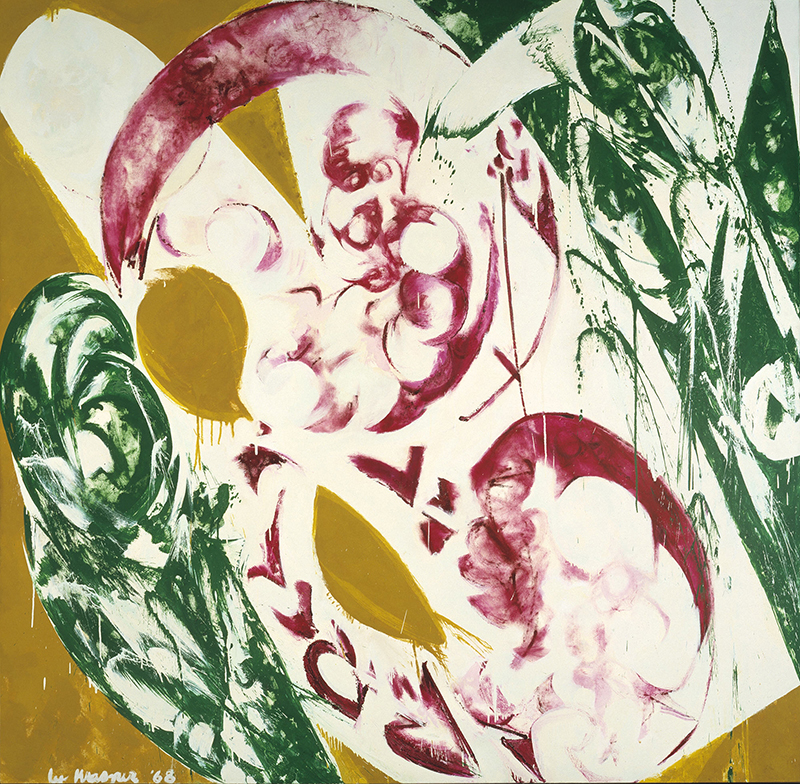

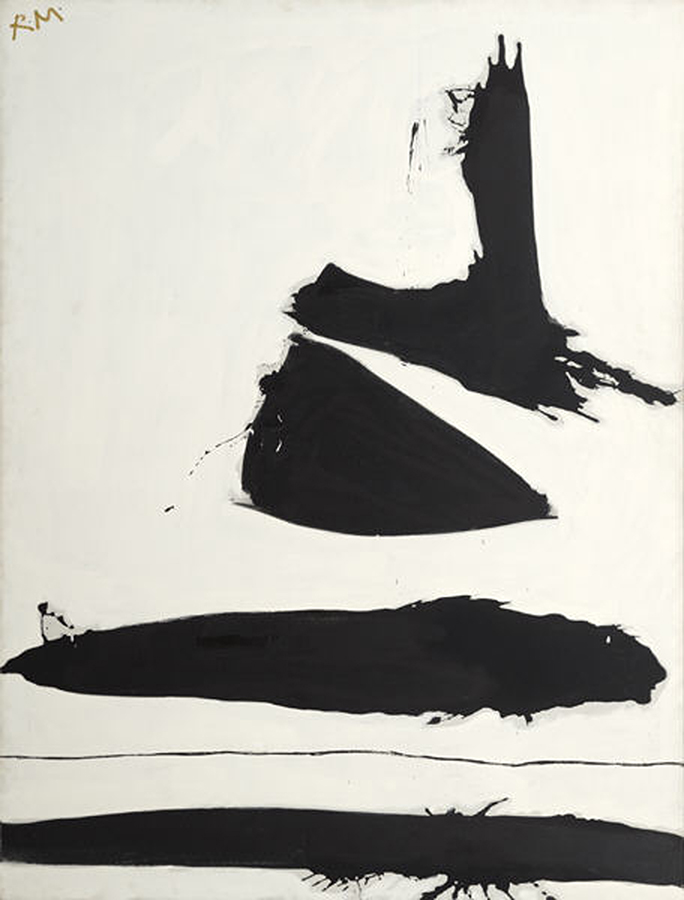

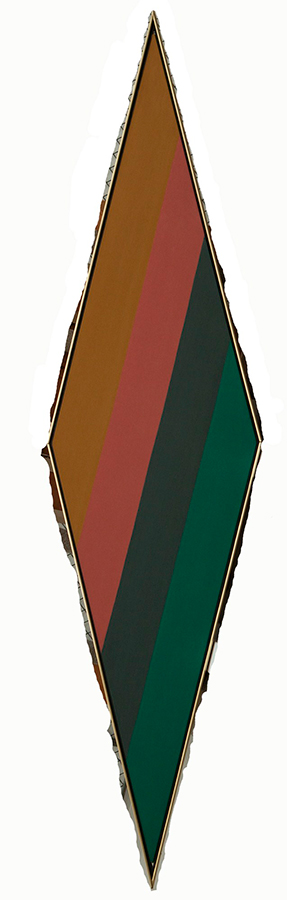

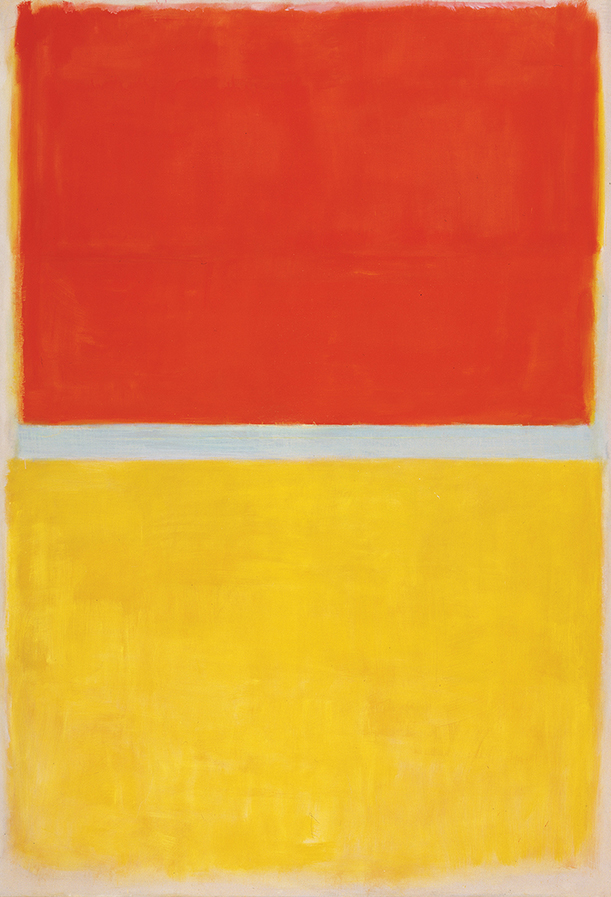

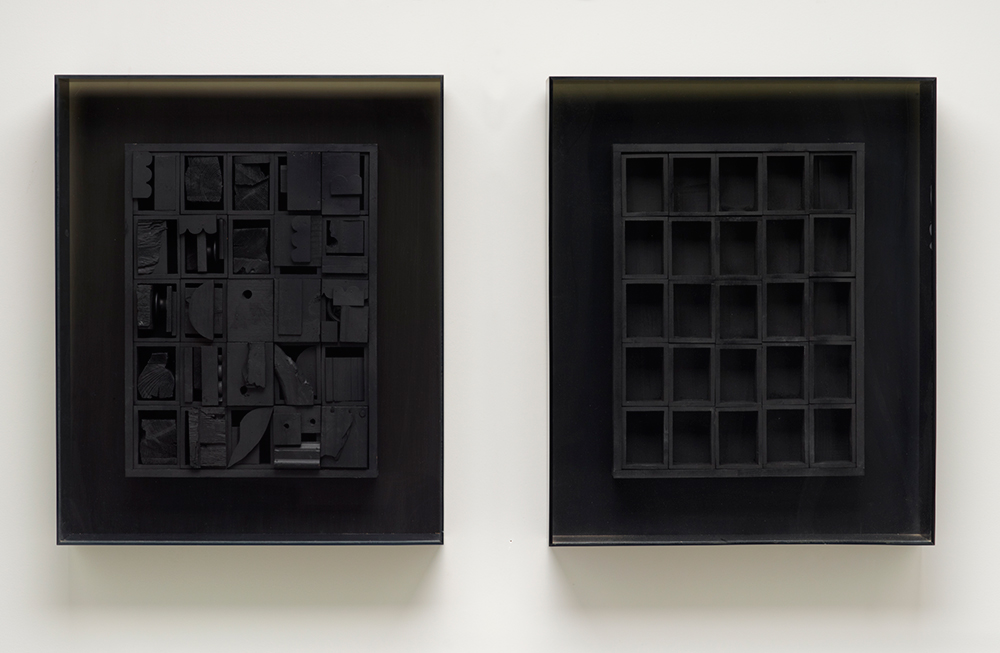

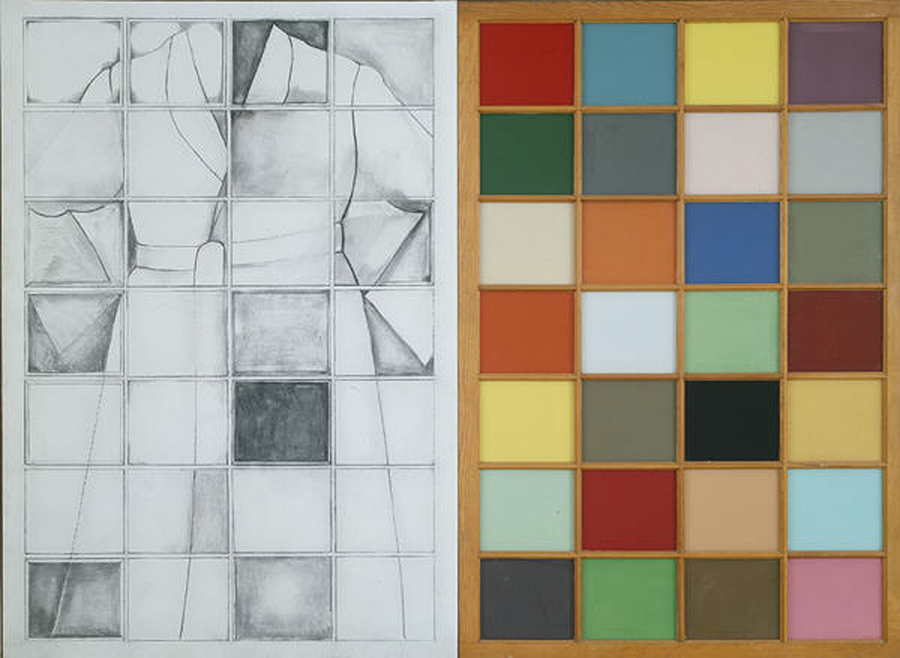

While curator of contemporary art, Murdock oversaw the acquisition of several major works of art, including Jasper Johns’ Device, 1961–1962 (Fig. 22), which was a gift to the Museum by the Art Museum League, Margaret J. and George V. Charlton, Mr. and Mrs. James B. Francis, Dr. and Mrs. Ralph Greenlee, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. James H. W. Jacks, Mr. and Mrs. Irvin L. Levy, Mrs. John W. O'Boyle, and Dr. Joanne Stroud in honor of Mrs. Eugene McDermott. Other important works acquired during Murdock’s tenure include: Jules Olitski, Mojo Working, 1966 (Fig. 23); Lucas Samaras, Transformation: Mixed, 1967 (Fig. 24); Larry Poons, Untitled #22, 1972 (Fig. 25); Robert Morris, Untitled, 1965–1966 (Fig. 26); and Tony Smith, Willy, designed 1962, fabricated 1978 (Fig. 27).

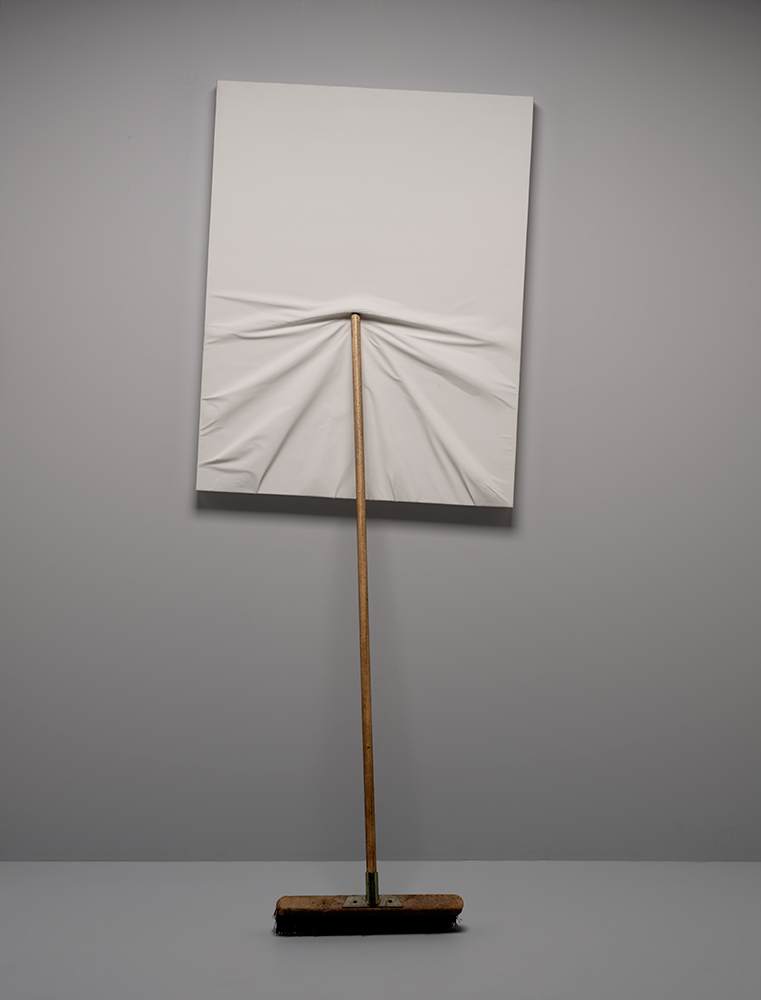

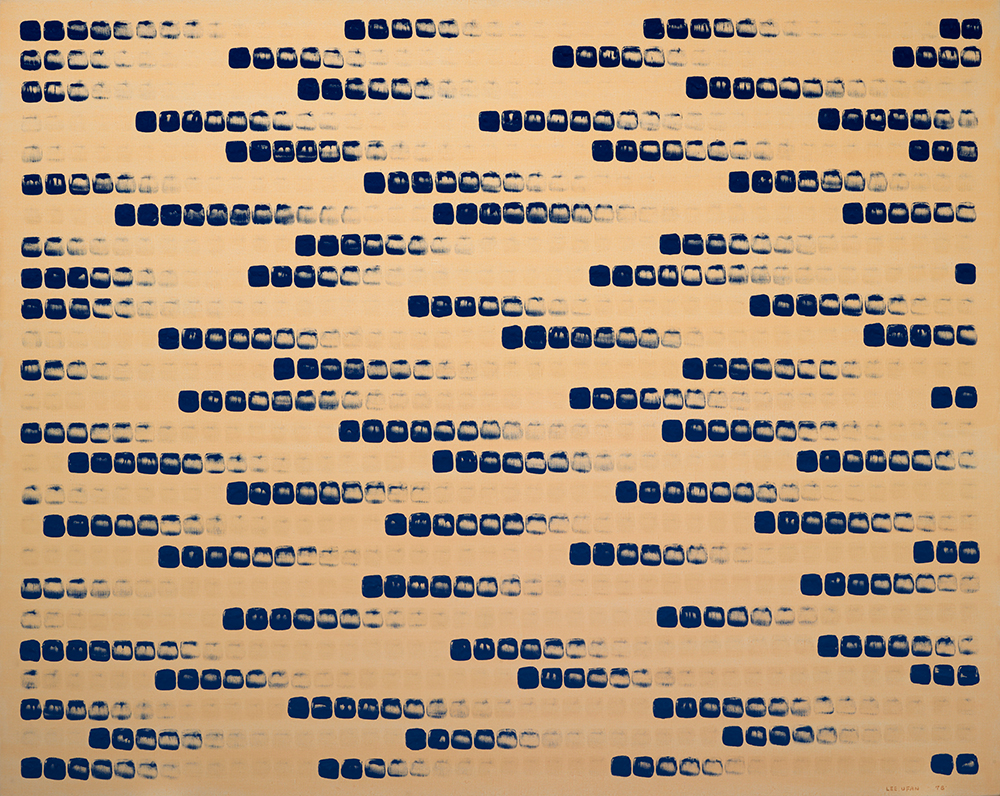

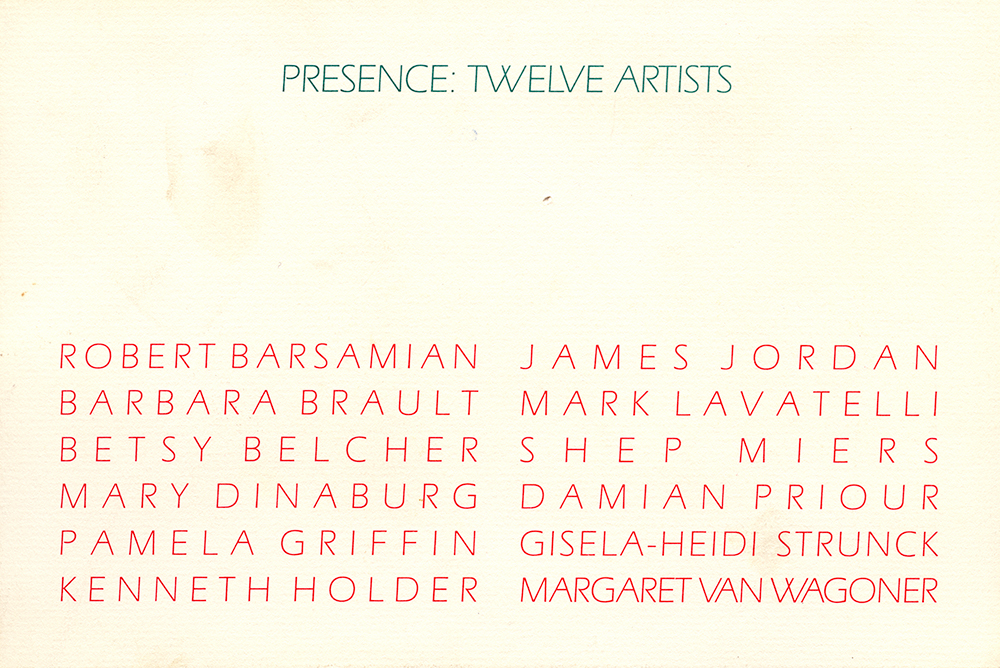

After Murdock’s departure in 1978, the Museum found itself without a curator of contemporary art for the next three years. Director Harry S. Parker III continued Rueppel’s transformation of the regional museum by expanding international collections and staging major exhibitions. In an attempt to continue some interaction with the local art scene, Parker organized 12: Artists Working in North Texas by appointing as curators three established local artists who developed a group exhibition surveying the work of regional artists. Jeanne Koch, David McManaway, and Mac Whitney selected artists they thought best represented the state of the arts in North Texas (Fig. 28, Fig. 29). This group show was the first and last of its kind.

In 1981, Parker appointed Sue Graze as curator of contemporary art. As one of her first orders of business, Graze developed the exhibition series Concentrations, which presented the work of emerging and midcareer contemporary artists in small, tightly conceived exhibitions that were intended to “present the depth and range of an individual’s work, thus serving as an index to recent developments in contemporary art.” The inaugural exhibition featured work by Fort Worth–based artist Richard Shaffer. The series has continued off and on at the Museum up to the present. As of 2012, there have been 55 Concentrations exhibitions by local, regional, and international artists.

Despite all the activity in and around Fair Park, the area was a relative ghost town during the off-season. As low-income housing developed to the south of the fairgrounds and the demimonde culture of nightclubs and tattoo parlors developed to the northwest in Deep Ellum, the neighborhood of South Dallas became increasingly crime-ridden. Access to the Museum was a chief concern for many patrons and board members, who typically lived in areas north of Fair Park or in the suburbs. Getting to and from the Museum meant traveling through neighborhoods that provoked unease, particularly after dark. Aside from a major retrospective of African-American art—Two Centuries of Black American Art—in 1977, the DMFA failed to provide programming or regular exhibitions of work by artists who represented the demographic of the Museum’s immediate audience in South Dallas, as Dallas Morning News columnist Janet Kutner noted:

Located as it is in the midst of a black area, DMFA has, it seems to me, a major responsibility to open its doors (with effort made to attract other than school tours) to the inhabitants of its immediate environs. Whether this requires shows of special interest or simply a better effort to draw the neighboring community in by specific invitations or programs until such visits become less rare and more frequent is a matter to be decided. What does seem certain, however, is the DMFA has a community at its doorstep with which it has essentially no relationship whatsoever. Quite a different situation from that here in Houston and elsewhere in the country where patrons as well as museums are taking art to the people rather than waiting for the people to come to it.

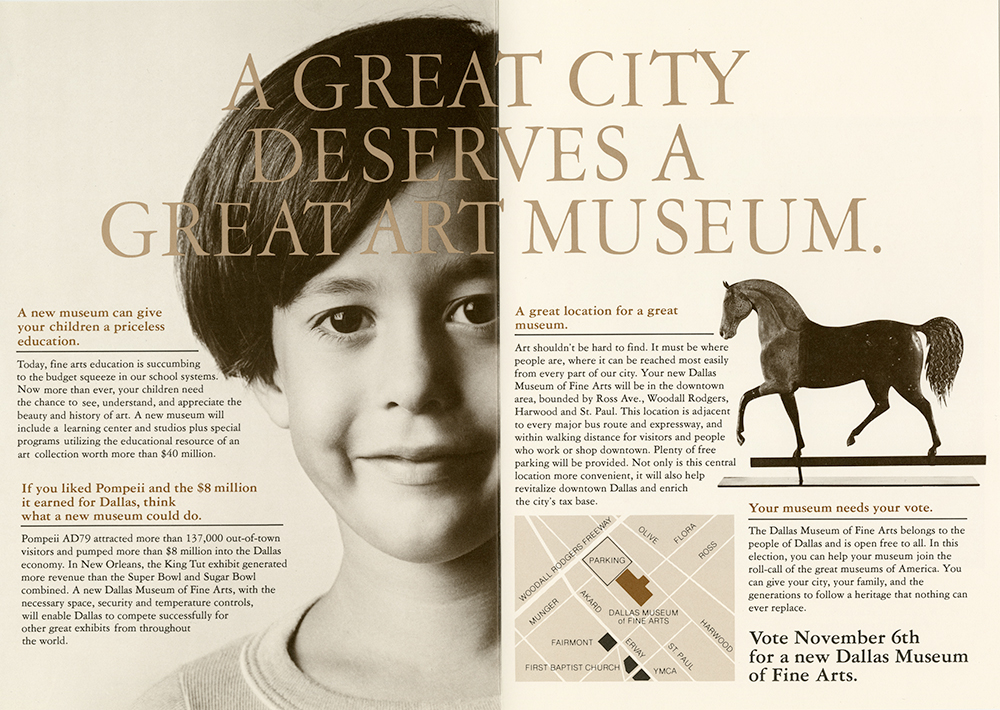

The DMFA had already expanded its Fair Park building once, during Merrill Rueppel’s directorship in 1965. Now the need for a larger facility was becoming more apparent, as both exhibitions and the permanent collection grew in size. Rather than expand the existing building, board members and DMFA administrators looked at options for a new building in a new, more accessible location. Using the slogan, “A Great City Deserves a Great Art Museum,” they campaigned to Dallas voters, who passed a $24.8 million bond issue in 1979 allowing the Museum to leave the increasingly undesirable Fair Park area for a new arts district being planned for the northeast corner of downtown. Today’s Dallas Arts District was born in 1984 with the opening of the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Dallas Symphony followed not long after.

The loss of a major cultural institution had a deep impact on the arts and culture in and around Fair Park and South Dallas. Artists who had lived and worked there relocated to other neighborhoods, and for some time, few commercial or alternative art spaces remained. Efforts to revive the area were unsuccessful until the South Dallas Cultural Center (SDCC) opened just outside Fair Park in 1986. Nearly two decades in the making and funded by a 1982 bond issue, the center was part of a city program to provide arts facilities for neighborhood and community organizations. Tapping into the audience that eluded the DMFA during its time in Fair Park, it gave African-American and other minority artists a venue for recognizing and nurturing local talent. Today the 34,000 square-foot, city-owned facility—expanded in 2007—boasts a 120-seat theater, a visual arts gallery, and studios for dance, music recording, and various visual art forms. Over the years, SDCC leaders have maintained the central mission to showcase the heritage of the African Diaspora and generate pride in the African-American experience.

When artist Vicki Meek became the center’s manager in 1997, she focused on improving its connection with the community. “A lot of people came and thought this was the parole office because the parole offices down the street didn’t look much different,” Meek recalls. “You know, cinderblock building, nothing to really distinguish it. And more importantly, the community didn’t have any real engagement in this building as far as the programming.” To help bridge the gap, Meek initiated programs like Late Night Jam, which featured local jazz musicians from midnight until 3 a.m., and a visual arts program aimed at young students from the community.

The South Dallas Cultural Center thrives as the hub of the Fair Park–South Dallas neighborhood in 2013. Over the years, several commercial galleries and alternative spaces have occupied the storefronts below the old 842 and Irwin Tuttie galleries. Spaces like Eugene Binder (1988–1993, Fig. 30); David Quadrini and Elliott Johnson’s Angstrom Gallery (established in 1996, Fig. 31); Dina Light and Steven Cochran’s gallery: untitled (established in 1997), and Jason Cohen’s Forbidden Gallery and Emporium (established in 2000, Fig. 32), kept the area fresh with activity into the 21st century. Just south of Dallas’ City Hall, Joe Allen’s Purple Orchid Gallery (2000–2002) and Randall Garrett’s Plush (established in 2000) occupied a warehouse on South Akard Street that also included artists’ working studios. Although they were separate ventures, both galleries were named Best New Gallery by the Dallas Observer in 2001, presumably due to their shared address.

In 2003, the Southside Artist Residency program introduced visiting artists to the neighborhood, and many of them kept studios there after their residencies had concluded. When the program was reintroduced as CentralTrak, the University of Texas at Dallas Artists Residency, it continued the spirit of the live-work studios and exhibition spaces that existed in the neighborhood some 30 years earlier. Through artist-run spaces and established anchors like the South Dallas Cultural Center and CentralTrak, the Fair Park–South Dallas neighborhood remains a vital part of the Dallas art macrocosm, sharing attention and activity with its neighbor, Deep Ellum.

Uptown: The Original Gallery District

The neighborhood now known as Uptown has gone by different names over the years. Bordered by the Dallas North Tollway to the west, Woodall Rodgers Freeway to the south, and Central Expressway to the east, Uptown was once defined by the streets that cross its interior: Maple, Oak Lawn, Cedar Springs, and Fairmount. The area came into its own in the late 1950s and 1960s, when it was likened to New York’s Greenwich Village. A group of up-and-coming artists— assemblagists David McManaway and Roy Fridge, sculptor Herb Rogalla, and painters Roger Winter and Bill Komodore—moved into the affordable bungalows that lined the streets of Oak Lawn and became loosely identified as the Oak Lawn Gang. These artists created a close-knit community, hosting “moonshine” parties where it was not unusual for guests to come in costume and dance to music by Fridge on tub bass and Winter on guitar. Winter recalls those gatherings:

One spring night in 1963, David [McManaway] called me from the Standup Bar and asked me to bring my guitar there. He said that a large group from the DMCA membership and staff had dropped by for a beer and that Roy [Fridge] had his tub bass and he had his banjo. When I got there, the group had literally taken over the place. I got into the mood of it, and we played for several hours. A drunk redneck at the bar danced by himself right through to the end. When we left, this guy shook my hand and said I “had it.” I consider this the best and purest compliment I have ever received.

Inexpensive housing was not the only appeal. The city’s earliest galleries and art spaces also opened in the neighborhood and employed many of the artists who lived nearby. Atelier Chapman Kelley, C. Troup Gallery, Nye Galleries, and Cushing Galleries were all established by the 1960s, and Uptown gained its first art museum when the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts (DMCA) moved to Turtle Creek in 1959.

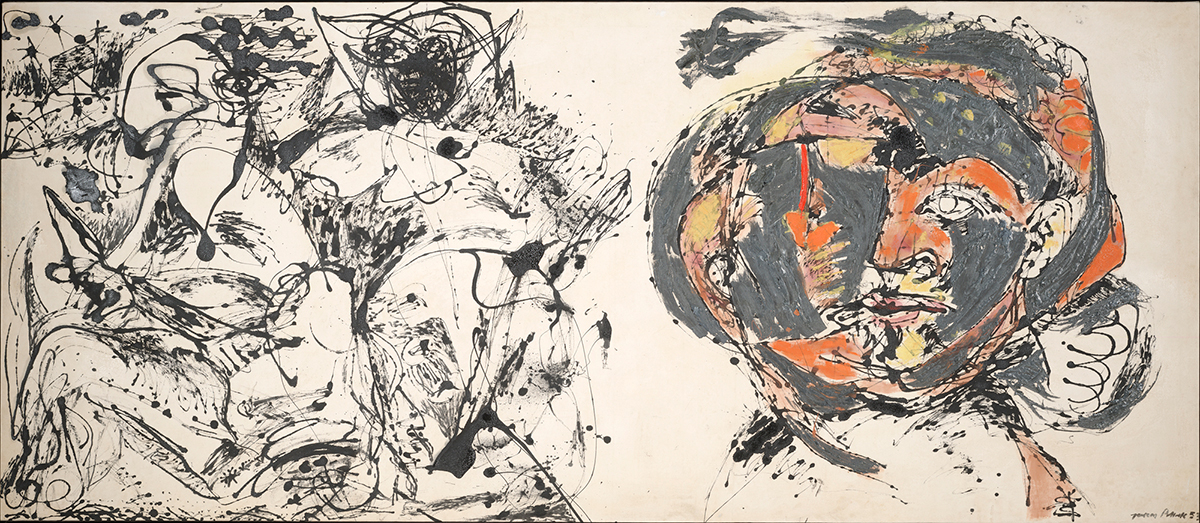

A Vibrant but Short-Lived Contemporary Art Museum

The Dallas Society for Contemporary Arts (DSCA) was established in 1956 by a group of artists, architects, theater directors, photographers, and critics led by the sculptor Heri Bert Bartscht. The DSCA organized exhibitions at the Courtyard Theater off Maple Avenue in Uptown until it opened a permanent location at the Preston Shopping Center in North Dallas in November 1957, officially becoming the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts. In its new space, the museum held several important exhibitions organized by board members. The inaugural exhibition, Abstract by Choice, featured work by Stuart Davis, Max Weber, Marsden Hartley, and Piet Mondrian on loan from major New York galleries and museums, including the Downtown Gallery, the Sidney Janis Gallery, and the Museum of Modern Art. Other notable exhibitions included Action Painting, with work by Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, Richard Diebenkorn, Jackson Pollock, and Franz Kline, and Laughter in Art, organized by board member Betty Blake, featuring Joseph Cornell, Dallas artist Roy Fridge, Jasper Johns, Houston artist Jim Love, Robert Rauschenberg, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Recognizing the need for a more cohesive and ambitious exhibition program and an advisor on acquisitions, the DMCA board began the search for a director while also looking for a new home for the expanding museum. By late 1959, art historian and museum administrator Douglas MacAgy was named director, and the museum moved to the former Slick Airways building at 3415 Cedar Springs Road in Uptown. MacAgy oversaw a rigorous exhibition schedule, which included important shows like Signposts of Twentieth Century Art, curated by art historian, critic, and art dealer Katharine Kuh of Chicago; Contemporary Japanese Painting and Sculpture; the first retrospective exhibition in North America of René Magritte, in collaboration with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Art of Assemblage; and 1961.

The exhibition 1961 generated controversy in the Dallas–Fort Worth art communities over two commissioned works by the contemporary sculptor Claes Oldenburg. For Store, which seemed to be the more traditional of the two, the artist transported his New York installation of mundane objects made of plaster to a gallery at the DMCA and reinstalled them to resemble a storefront (Fig. 1). The work is now considered a prime example of pop art, which elevates the everyday to the status of art object. But local reactions at the time ranged from minor discomfort to a full-blown visceral reaction by Fort Worth artist Bror Utter, who took a bite out of a plaster slice of pie at the opening. Roger Winter describes the incident:

Claes had a slice of like a meringue pie. I think something like a lemon pie, coconut pie made of plaster and enamel and probably burlap and chicken wire as the structure of it, and it was sitting on a little saucer on a chair that he’d borrowed from David and Norma McManaway, a blue chair—just an old-timey kitchen chair—and a painter from Fort Worth, . . . Bror Utter, came with a friend of his, Sam Cantey, who was, I think, president of one of the better banks in Fort Worth. And Bror, I think, got a little drunk and he was so outraged by all of this [Oldenburg’s installation] that he picked the piece of pie up off the chair and bit a piece out of it. . . . That seems always to me to be a remarkable reaction to art.

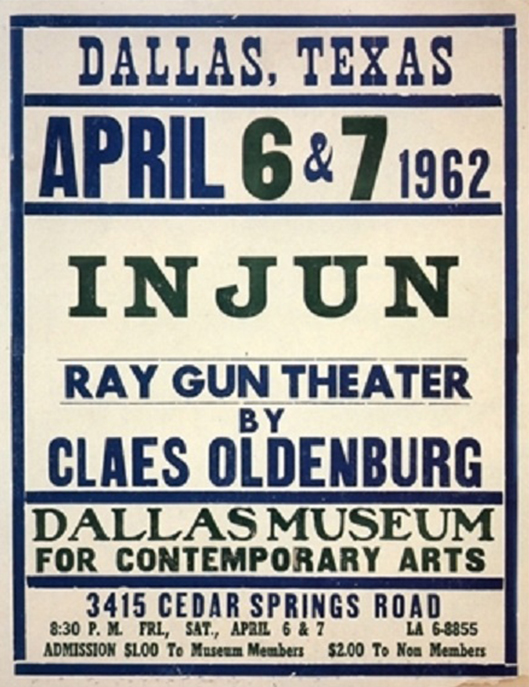

Oldenburg’s other commissioned work for 1961 was perhaps the most infamous event at the DMCA: the first of the artist’s “happenings” outside of New York City and the first commissioned by a museum. Titled Injun, it was performed on the DMCA grounds on two evenings (Fig. 2). With his wife Pat, DMCA staff, and painting students from the University of Texas at Arlington, the artist took over an abandoned house and guided visitors through various room installations to the sounds of Native American drums and chants. In the climax of the performance, Oldenburg dragged his wife’s limp body onto the roof of a shed behind the house and chopped a tornado-like object made of papier-mâché. Winter has these memories of the happening:

Joe Hobbs is the painter who taught at Arlington State [now the University of Texas at Arlington] at that time. . . . And he and a group of his painting students all were wrestling around on the floor. Hal Pauley was in the room with some newspapers playing, or pretending to play, a violin. There were just rooms in this house, and Claes was dressed up like an Indian in . . . some kind of savage-looking costume made out of shredded papers. He was dancing and moving around. . . . To view it we held on to a rope and sort of moved in through the rooms in the building that belong to the DMCA, moved in a certain direction. And I heard someone say behind us, “Boy, the membership in the DMFA is going to skyrocket tomorrow! . . .” Because it was so different for Dallas at that time.

MacAgy earned great respect and admiration from local artists—some of whom worked on the museum staff—because he included them in major exhibitions alongside artists with national recognition. David McManaway and Jim Love were part of the Dallas showing of the traveling exhibition The Art of Assemblage, while Roy Fridge designed exhibition catalogues for 1961 and The Art that Broke the Looking Glass and exhibited his own work in 1961. Many artists were disappointed when the DMCA merged with the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1963, fearful that the loss of their powerful and loyal ally in the highest ranks of the museum community would mean a return to the less-visible status quo, with fewer opportunities to show their work. Winter recalls his fondness for MacAgy and the environment surrounding the DMCA:

Douglas was the nucleus, the star, the center. . . . And I think he generated quite a bit of it [energy], but then we were some interesting characters there and this was the time when we lived in what I’d call an “exotic poverty.” None of us had any particular money, but we worked and we were very excited about our work and there was a lot of interchange. I especially was influenced by . . . David McManaway, but also Roy Fridge. Jim Love lived in Houston, but he flew up to, ironically, Love Field, to Dallas.

In addition to major exhibitions and acquisitions—like Henry Matisse’s Ivy in Flower, 1953 (Fig. 3), Paul Gauguin’s Under the Pandanus (I Raro te Oviri), 1891 (Fig. 4), and Francis Bacon’s Walking Figure, 1959–1960 (Fig. 5)—the DMCA offered community programs such as the Children’s House, directed by Paul Rogers Harris with Peggy Wilson (Fig. 6), and a weekly film series organized by board members Major and Downing Thomas. After the merger, Harris moved his children’s art program to the Little Red School House at KERA-TV Channel 13, the local public television station, where he continued to offer instruction in painting and graphic arts.

The DMCA’s move to Uptown stimulated the district’s already-burgeoning arts activity. Through his contacts at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, local artist and gallery owner Chapman Kelley brought in East Coast artists for exhibitions at his Atelier. Eventually, his roster included new-to-Dallas artists Jeanne and Arthur Koch and arts and technology whiz Alberto Collie, who dazzled Dallas audiences with his floating sculptures.

Mary Nye’s Nye Galleries focused heavily on artists who taught at East Texas State University, as well as emerging and established regional artists like Dallas sculptor Heri Bert Bartscht, Texas painter Cecil Casebier, and local painters DeForrest Judd and Otis Dozier (Fig. 7). Local painter Bill Komodore once commented that the Nye Galleries’ walls were covered in burlap and that Mary Nye herself “was like a New York dealer, in that she would never bother to look at your work (Fig. 8).” Despite this lighthearted criticism, Nye was seen as a serious gallerist, putting on exhibitions and representing artists for the next two decades.

A Gallery District Emerges

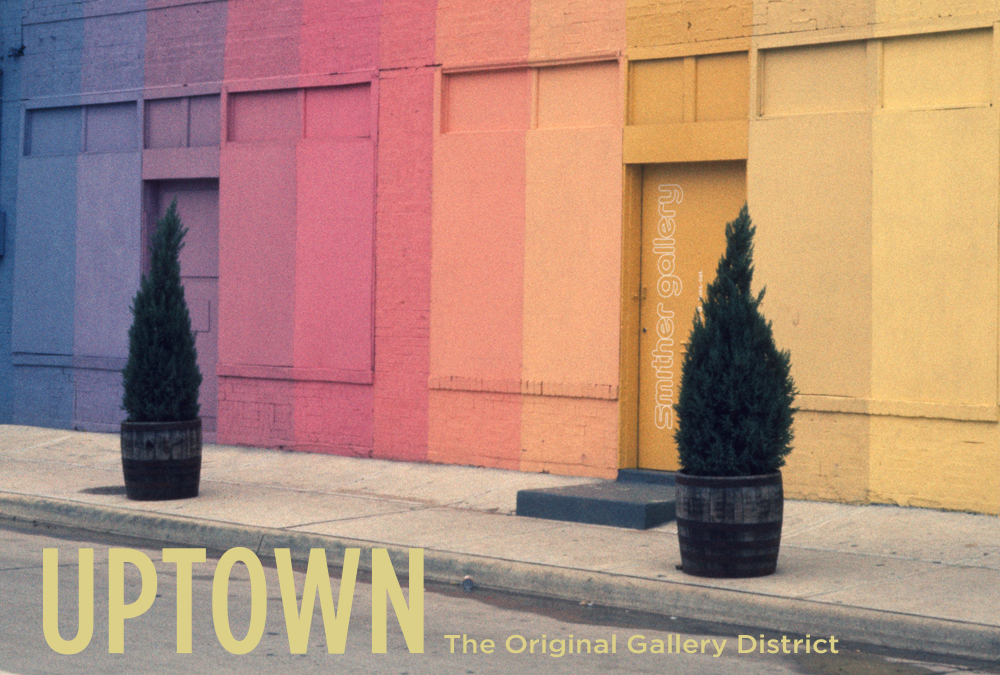

By the 1970s, the success of several galleries had turned Uptown into a true gallery district. While do-it-yourself spaces were the norm in other active parts of town, like South Dallas, the Uptown galleries had a more polished, commercial presence. Their approaches varied. Some, like Janie C. Lee Gallery, chose to bring the national art scene to Dallas. Others, including Smither Gallery, exhibited both national and local artists. Still others, like Delahunty Gallery, put Dallas artists on a national stage. The Uptown neighborhood was also home to Dallas’ first photography galleries: Afterimage, established in 1971 in the Quadrangle by Ben Breard, and the Allen Street Gallery, a do-it-yourself space opened in 1975 on Allen Street that developed into a recognized commercial gallery.

Like Allen Street Gallery, the Dallas Women’s Co-op started as a cooperative gallery space, with its members staffing the gallery and paying dues in exchange for exhibitions (Fig. 9). It was established in 1975, just two years after Judy Chicago and other women artists opened the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles at the height of the second-wave feminist movement. The women behind DW Co-op wanted a similar space where local women artists could control what work was exhibited and how. Over the decades, DW Co-op named a governing board, changed its name to DW Gallery, and began giving exhibitions to men and women. The first exhibition to include men featured the work of locals Sam Gummelt and David McManaway with Houston sculptor Jim Love. Notable exhibitions included Wearable Works (1978); Gift Wrap (1979), with works on the theme by former Dallasite Rick Maxwell, Gilda Pervin, Tom Orr, and other gallery artists; and Book Exhibit (1982), curated by gallery director Diana Block. Some of the emerging artists who showed there—including David Bates, Clyde Connell, Danny Williams, and Otis Jones—went on to enjoy national reputations. What started as a 500-square-foot gallery space above a restaurant in Uptown expanded in 1983 into a Deep Ellum warehouse with more than 20 nationally known Texas-based artists on the roster and 2,400 square feet of exhibition space.

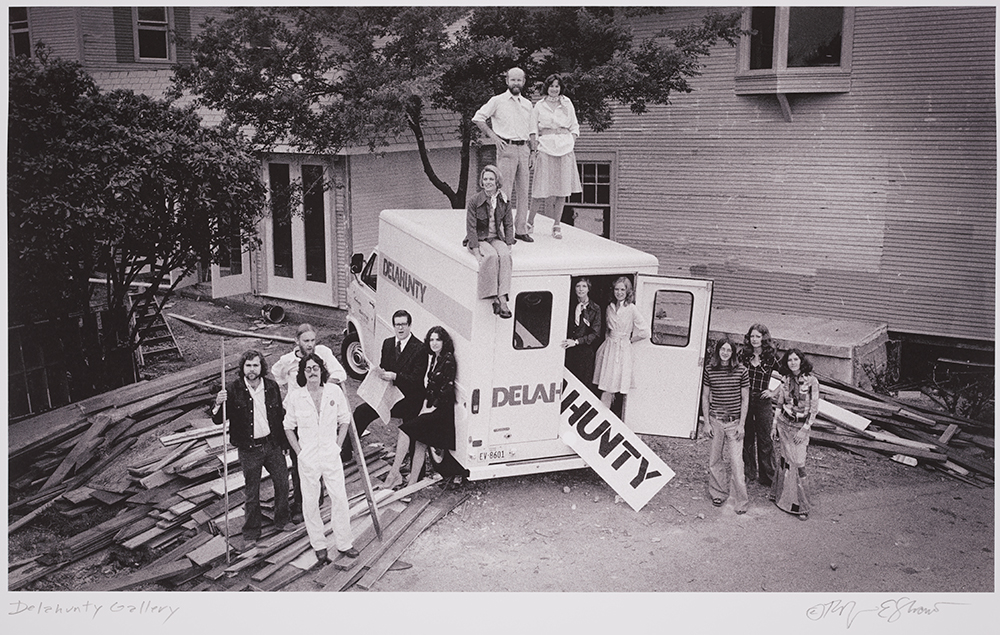

Two of the most successful galleries in the Uptown area were bookends for the 1970s: Janie C. Lee Gallery, established in 1967 (Fig. 10), and Delahunty Gallery, launched in 1974 by Laura Carpenter, Murray Smither, and Virginia Gable (Fig. 11). The two spaces fared differently in Dallas, owing in part to economics but also to timing. In some ways, the Janie C. Lee Gallery paved the way for a gallery like Delahunty, which enjoyed greater success even though it showed similar work.

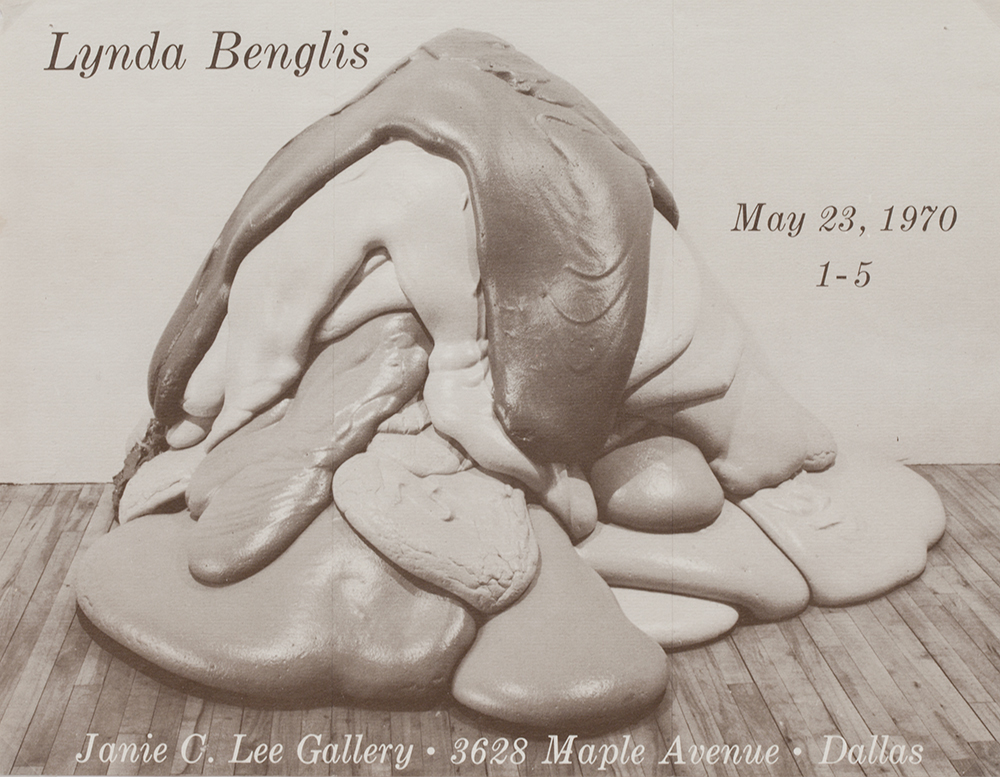

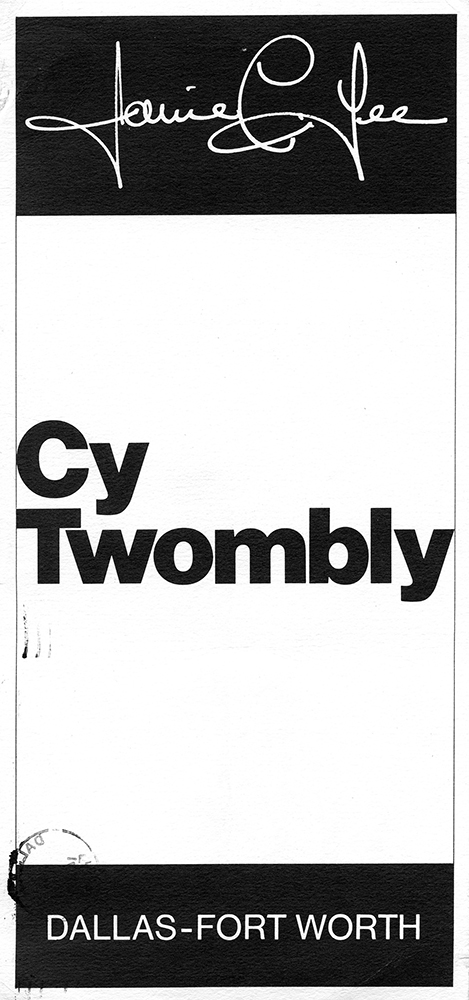

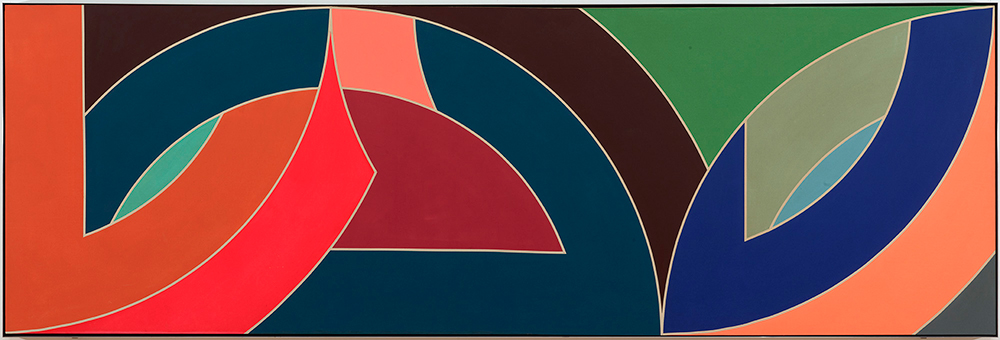

Janie C. Lee was ahead of her time for the artists and styles she introduced. She had spent several years in New York City, and she had the sophisticated taste and the right contacts to bring the national contemporary art scene to Dallas. Her relationship with New York gallery owner Leo Castelli was the source of much of her inventory, which she showed on consignment. In the early years, Lee ran the business from her apartment at 3525 Congress Avenue, but by 1970, the gallery had its own location at 3628 Maple Avenue. Highlights of exhibitions there included the 1969 exhibition of work by Frank Stella, Darby Bannard, David Diao, Robert Morris, Donald Judd, and Richard Serra; the 1970 exhibition Bengston/Price, by Californians Billy Al Bengston and Ken Price; the 1970 solo exhibition of work by Lynda Benglis (Fig. 12); and the 1972 exhibition New Paintings, Drawings, and Lithographs by Cy Twombly (Fig. 14). Lee’s minimalist aesthetic is reflected not only in the artists her gallery represented—Judd, Carl Andre, and Dan Flavin—but also in her 1976 gift to the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts of a Dan Flavin work dedicated to Donald Judd (Fig. 15). In 1973, Lee opened a branch of her gallery in Houston. In spite of critical success, the Dallas gallery closed in 1974, while the Houston branch stayed open until 1983.

Delahunty Gallery also earned a reputation for bringing big names to Dallas. While Lee’s gallery emphasized nationally known artists, Delahunty maintained a strong connection to local and regional artists. Over the years the gallery presented exhibitions by Dallas-based artists George T. Green, Jim Roche, Gail Norfleet, Bob Wade, Lee Baxter Davis, Vernon Fisher, Raffaele Martini, Dan Rizzie, Debora Hunter, Nic Nicosia, Danny Williams, and James Surls. The connection to this local base was gallery director Murray Smither, who was well established in the Dallas art scene as director of Atelier Chapman Kelley, director of the Cranfill Gallery, and owner of the Smither Gallery before joining forces with Laura Carpenter and Virginia (Ginny) Gable at Delahunty in 1974. Operating at first out of Smither’s gallery at 2817 Allen Street, Delahunty soon moved to 2611 Cedar Springs Road. It remained there for several years until expanding into a new location in Deep Ellum in 1982.

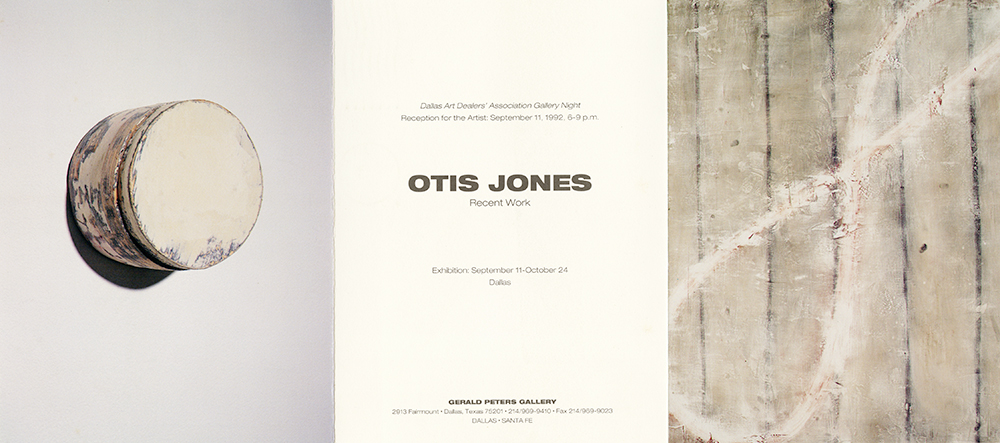

Commercial galleries remained the driving force behind the art scene in Uptown through the 1980s and 1990s, with spaces like Edith Baker, Mattingly Baker, and Gerald Peters Fine Art exposing Dallas art lovers to current work by local, regional, and national artists. Edith Baker has had a long history of supporting art and artists in North Texas. She and her husband immigrated to the United States from Bulgaria in 1949, arriving in Dallas via Chicago in 1951. Edith took classes at the DMFA, studying under Octavio Medellín. In the 1960s, with the help of her husband, she opened her own studio behind their home, where she taught art classes. By 1977, Baker had stopped teaching and opened a gallery called Collector’s Choice with two partners in North Dallas near the intersection of Preston and Royal Lane. With a principal focus on decorative art and limited-edition prints, Collector’s Choice lasted until 1981, when the partnership ended. Baker renamed the space the Edith Baker Gallery, and by going out on her own shifted the focus to local artists, both emerging and established. In 1987, Baker moved her gallery to the Uptown area to be closer to the gallery district action. Baker retired in 2001 and handed over the reins to director Cidnee Patrick.

Aside from her gallery, Baker helped establish two organizations that focus on collaboration and community: the Dallas Art Dealers Association (DADA) and the Emergency Artists Support League (EASL). In 1985, Baker and 11 other gallery owners formed DADA as a way to encourage collaboration and synergy among the growing number of Dallas galleries (Fig. 16). Baker recalls the climate of the burgeoning gallery scene in the mid-1980s:

First of all, we never talked to each other. The galleries had no reason to talk to each other, and you didn’t know anybody. And so I think all of us were wondering what we could do, because I thought how other cities have their associations and we don’t have one. . . . We all had thought about it but June Mattingly was the one who assembled us into 12 galleries. . . . And the atmosphere changed . . . completely because we started communicating with each other.

Activities sponsored by DADA include twice-yearly art walks and the Edith Baker Scholarship Fund, named in Edith’s honor starting in 2005. Today, DADA has more than 30 members.

With local arts administrator and artists’ advocate Patricia Meadows, Baker created the Emergency Artists Support League (EASL) in 1992 to provide emergency grant funding to visual artists and visual art professionals in North Texas. Baker came up with the idea after seeing the Houston organization DiverseWorks come to the aid of local artist James Bettison following a series of misfortunes. When Dallas-based artists Nancy Chambers and Tracy Hicks each encountered health problems, the local arts community came together, with Baker and Meadows at the helm. A volunteer steering committee solicited donations in the first six months of EASL’s existence. Later fundraisers included an artist-designed coloring book (Fig. 17); the Tie One On benefit auction of artist-designed or -altered neckties in 1993; the Hats Off to EASL benefit auction of artist-designed or -altered hats in 1994; the Hot Flash benefit auction of artist-designed or -altered candlesticks in 1995; and the annual Art Heist, which started in 2006. Since 1992, EASL has given North Texas artists more than $320,000 in emergency funding. As Baker recalls,

EASL was the project that I'm really, really proud of. It is so difficult to help artists. We don’t know what to do for them. You know, it’s not like, “Here, let me give you some money.” This . . . was just a good project that really worked well for everybody and nobody could be more grateful than the artists. . . . Those moments of EASL, I think, were probably my best memories because we worked like Trojans, you know, to put up a show if we could get the space that we wanted.

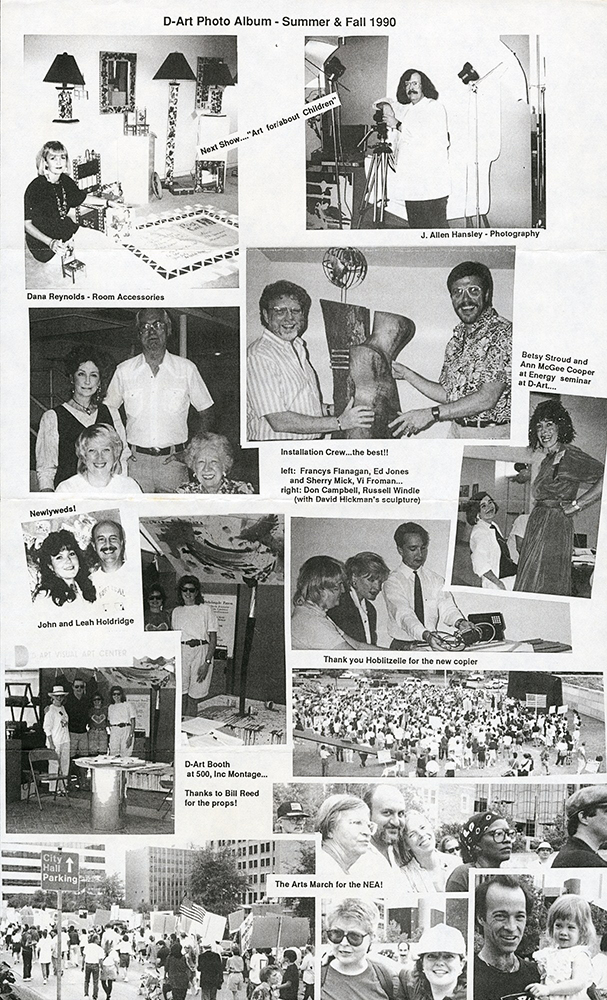

DARE and The MAC

In 1994, McKinney Avenue Contemporary (The MAC) opened as a nonprofit space representing local, regional, national, and international contemporary artists. The MAC is the physical manifestation of several years of work by Dallas Artists Research and Exhibitions (DARE), which started in 1989 as a series of informal conversations between cofounders and friends Greg Metz and Tracy Hicks. Their talks led to organized meetings involving like-minded artists and covering topics like the need for greater art media coverage, ways around the “stagnant gallery scene,” and gaining greater exposure. At the heart of many of the discussions was the need for an organization to nurture and support serious, experimental artists of any medium and provide an alternative voice in the Dallas art community. As membership grew, so did DARE’s activities. In its first five years, the group organized the first Texas Biennial exhibition at the Fair Park Food and Fiber Pavilion; presented a Dialogue Series that brought national scholars and critics to Dallas, including preeminent modernist art critic Clement Greenberg; organized a rally in support of the National Endowment for the Arts (Fig. 18, Fig. 19); and published a newsletter covering the Dallas art scene and the group’s activities. DARE also developed a strong relationship with the Dallas Museum of Art through its director Richard Brettell and earned a seat at Museum board meetings, giving local artists a voice at one of the most exclusive tables in town.

In December 1990, DARE rented a warehouse on the edge of Deep Ellum as a place to curate exhibitions and performances for local artists, but the space at 605 South Good-Latimer Expressway needed serious renovation. In early 1994, local arts patron Claude Albritton offered to renovate a one-story 18,000-square-foot building at the corner of McKinney and Oak Grove Avenues in Uptown, rent the space to DARE for $1 per year, and contribute a $100,000 programming budget. DARE was absorbed into The MAC, having achieved its goal of creating an organization that nurtures contemporary artists. Since its opening, The MAC has exhibited more than 275 artists, continues its lecture series, and sponsors an in-house theater company, the Kitchen Dog Theater.

Uptown in the New Millennium

Uptown maintained its status as the gallery district of Dallas through the new millennium. Important gallery spaces like Pillsbury & Peters Gallery, Afterimage, Dunn and Brown Contemporary, and Photographs Do Not Bend kept the area alive with regular exhibitions of contemporary art by local, regional, and international artists in a variety of media.

As the neighborhood’s oldest running gallery and the city’s first dedicated photography gallery, Afterimage continues to offer exhibitions of local and international photographers organized by owner and founder Ben Breard. Every Christmas, a large group exhibition features prints from the gallery’s stock. Breard and Afterimage were also founding members of the Dallas Art Dealers Association.

Dunn and Brown Contemporary was established in 1999 by former Gerald Peters Fine Arts director Talley Dunn and Lisa Hirschler Brown in a former design warehouse at the north end of Uptown. At Gerald Peters since 1993, Dunn had developed a strong group of collectors while establishing relationships with the gallery’s artists, many of whom followed her to Dunn and Brown: David Bates, Julie Bozzi, Vernon Fisher, Annette Lawrence, Nic Nicosia, and Linda Ridgway. The first exhibition at Dunn and Brown, titled Inaugural Exhibition, featured Helen Altman of Fort Worth, Matthew Sontheimer of Houston, and Liz Ward of San Antonio. The exhibition program gave regular solo shows to stable artists and brought in exhibitions by artists of international renown. During its 12-year run, Dunn and Brown gained a reputation for supporting established and emerging local and regional artists. Brown left the partnership in 2011 to work as a private art consultant, and Dunn continued the gallery in the same location under her name. In addition to solo exhibitions by stable artists, Talley Dunn continues to bring in international exhibitions, including shows of Philip Pearlstein and Helen Frankenthaler in 2011 and a major Dale Chihuly retrospective in 2012 that featured work installed in the gallery and at the Dallas Arboretum.

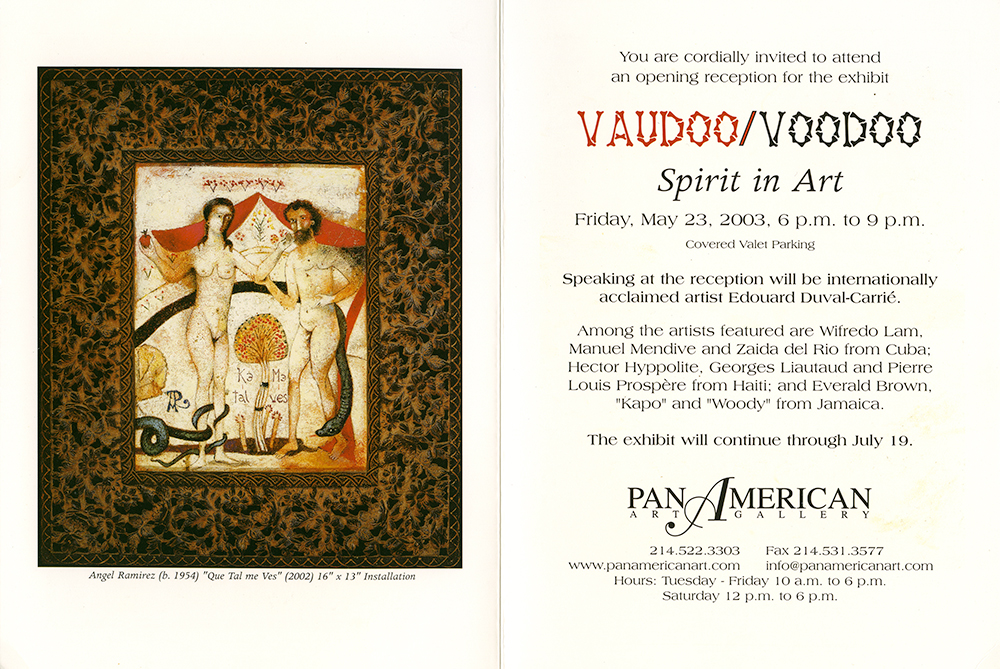

As an alternative to Afterimage Gallery, Photographs Do Not Bend (PDNB) focuses on 20th-century and contemporary photography and photo-based art. Owned and operated by Burt and Missy Finger since 1995, the gallery represents recognized artists from the United States, Latin America, Europe, and Asia. Also featured are artist monographs and out-of-print photography books. In 2005, PNDB relocated to its present location in the Design District, joining former Uptown galleries Craighead Green Gallery, Gerald Peters Gallery, and Pan-American Gallery.

The gallery migration to the Design District left Uptown with fewer options for viewing contemporary art. The neighborhood as a whole has transitioned in recent years to a lively dining and entertainment destination for young professionals. The number of residential properties has increased, and restaurants, bars, and nightclubs line McKinney Avenue and Cedar Springs Road. The West Village property development at Lemmon and McKinney Avenues further adds to the neighborhood’s attraction. Two anchor spaces—Talley Dunn Gallery and The MAC—maintain the neighborhood’s vital connection to local art communities. With the addition of Klyde Warren Park connecting Uptown to the Arts District, the opportunities for exchange between these two neighborhoods are only beginning.

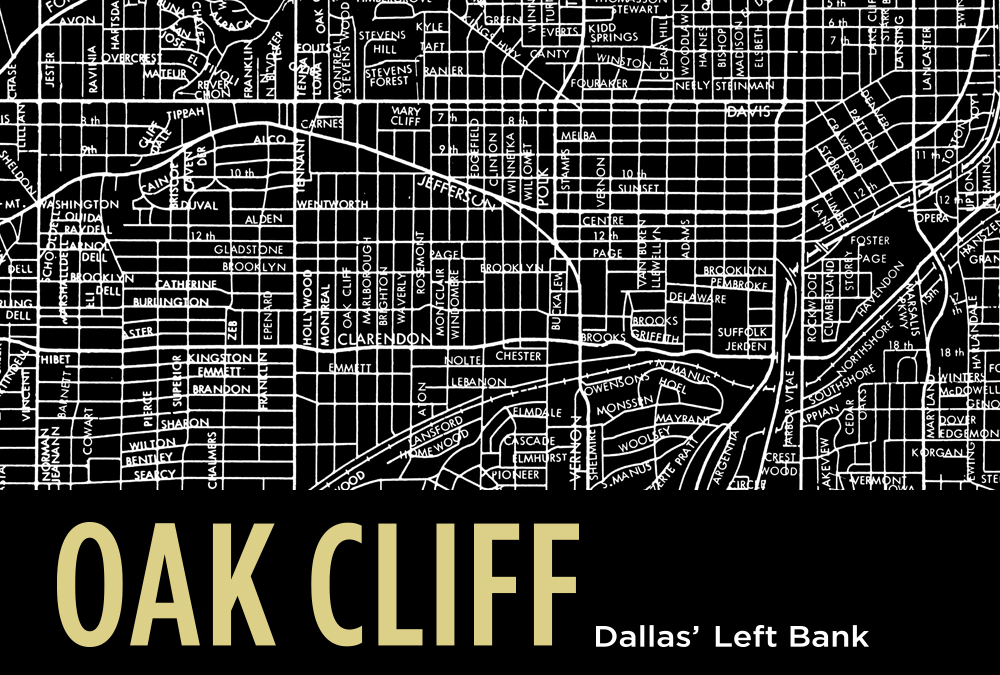

Oak Cliff: Dallas' Left Bank

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Oak Cliff became a lively creative enclave, earning its nickname as Dallas’ Left Bank. Local artists discovered opportunities in the available, affordable homes and former businesses in the declining area, and as they created studios and live-work spaces there in the late 1960s, the neighborhood blossomed as an arts community. Visual artists like the Oak Cliff Four moved in to live alongside Oak Cliff natives—actors and musicians like Yvonne Craig, Stevie Ray Vaughn, and T-Bone Walker. They followed earlier generations of artists, including Texas regionalist Frank Reaugh (1860–1945), who moved to Dallas in 1890 and established a studio in Oak Cliff, and Velma (1901–1988) and Otis Dozier (1904–1987), whose home was a frequent meeting place for Otis’ students from Southern Methodist University.

Bordered today by the Trinity River and interstate highways 30 and 35E, Oak Cliff was a separate town until it was annexed by the city at the turn of the 20th century. Historically, the neighborhood was a wealthy suburb, popular with upper-middle-class residents for its rolling hills and lush green landscapes. Though Oak Cliff has officially been part of Dallas for more than a century, people who live there have reveled in their outsider status, taking pride in a place that has the feeling of a small town nestled within a big city.

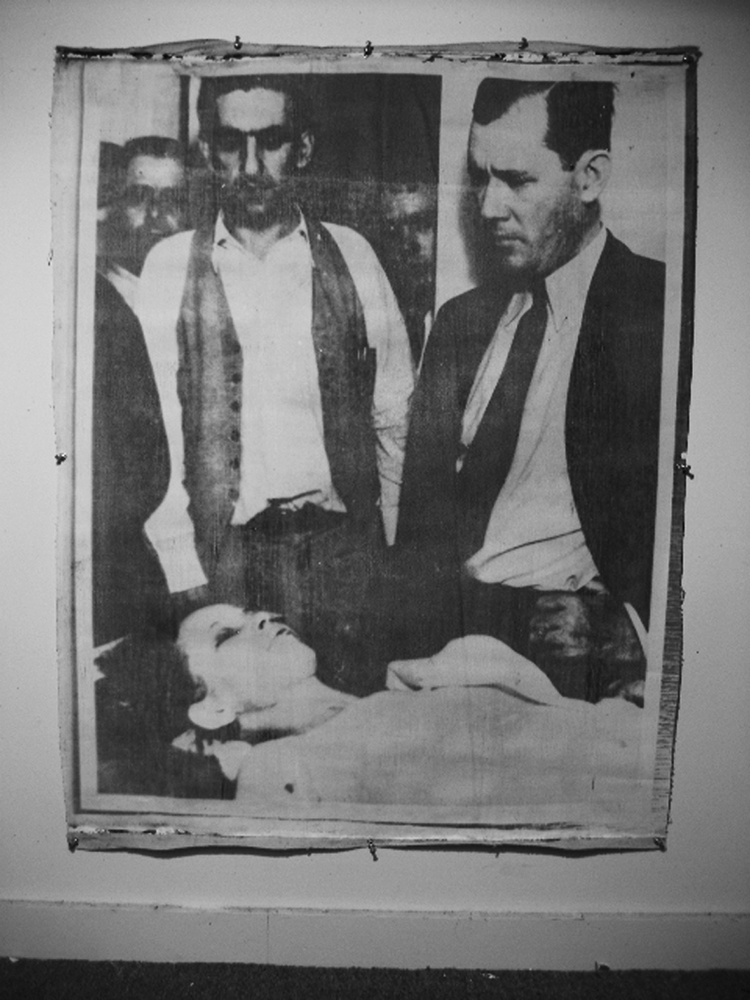

Oak Cliff has had a few notorious residents, including Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow and Lee Harvey Oswald. Oswald’s connection left a stain on the neighborhood in 1963. He was apprehended there in the historic Texas Theatre, near the boarding house where he lived, after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy downtown and the shooting death of Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit in Oak Cliff. These events—and the fact that Oswald’s killer, Jack Ruby, was also an Oak Cliff resident at the time—influenced the neighborhood’s reputation as a “lawless, useless zone.”

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964, South Oak Cliff was one of the first neighborhoods in Dallas to begin integration. African-American residents could now live in affordable, attractive homes in stable communities—a far cry from the overcrowded, crime-ridden conditions in South Dallas and State Thomas, where racist law and tradition dominated. The shifting racial demographics of Oak Cliff led to decreasing property values and large-scale white flight, as more and more white property owners left their homes vacant and moved to the developing suburbs in North Dallas. During this transition, Oak Cliff gradually fell into decline. While the area experienced a resurgence of activity when artists began moving there in the 1970s and 1980s, its artist communities remained stuck in the segregated past. There was little comingling then between African-American artists living in Oak Cliff—including Arthello Beck Jr. and Frank Frazier—and artists who relocated there in search of affordable space. Beck’s gallery remained focused on showing the work of African-American artists, and new galleries that opened in the late 1980s and early 1990s—such as Ann Taylor Gallery, Visions in Black, and Ebony Fine Arts Gallery—kept this racial focus. As the demographics have shifted in recent years to include a large Latino population, the Ice House Cultural Center and Steve Cruz’s Mighty Fine Arts have contributed to the growing diversity of the artist communities of Oak Cliff.

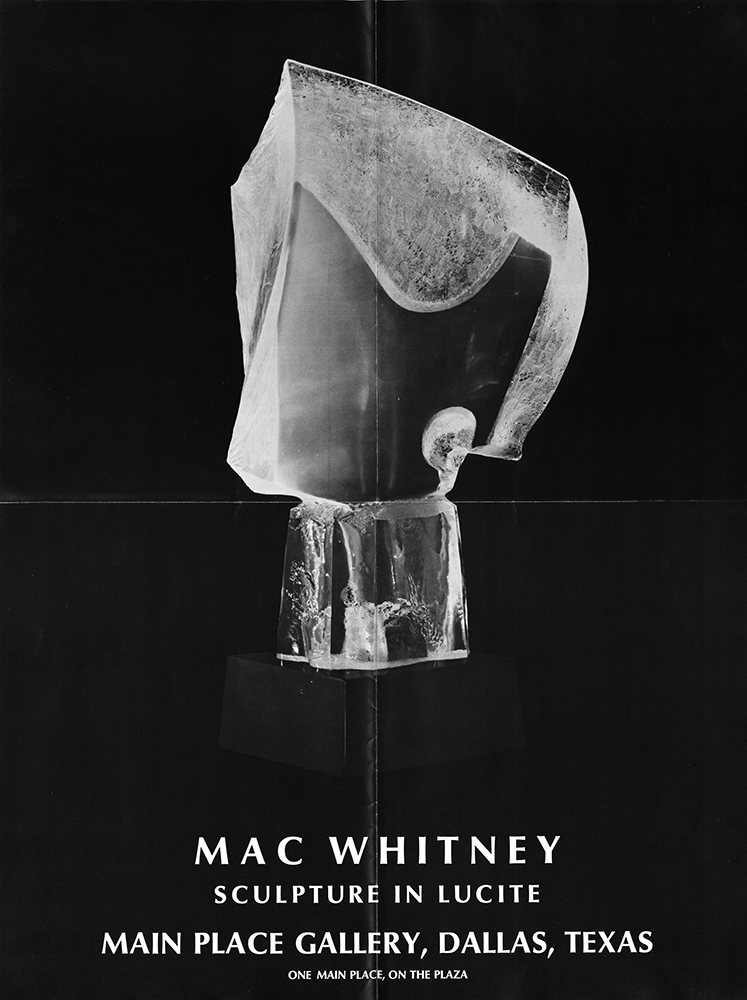

Oak Cliff Artists: 1970s

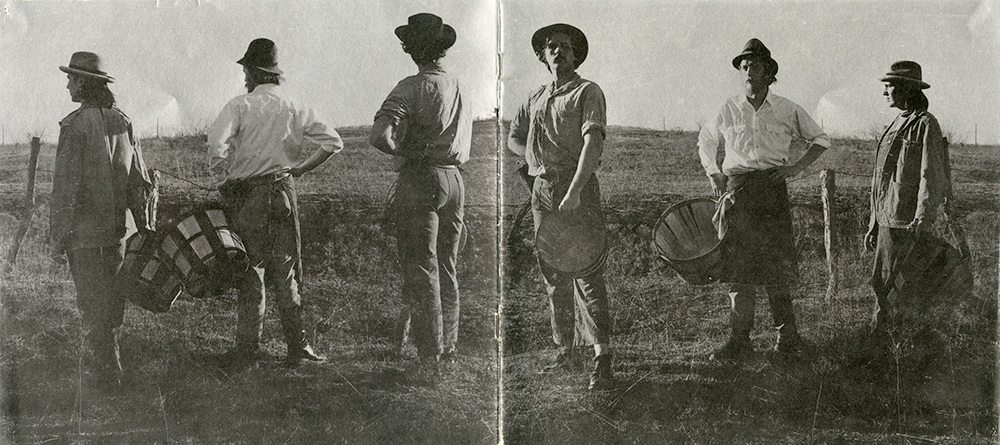

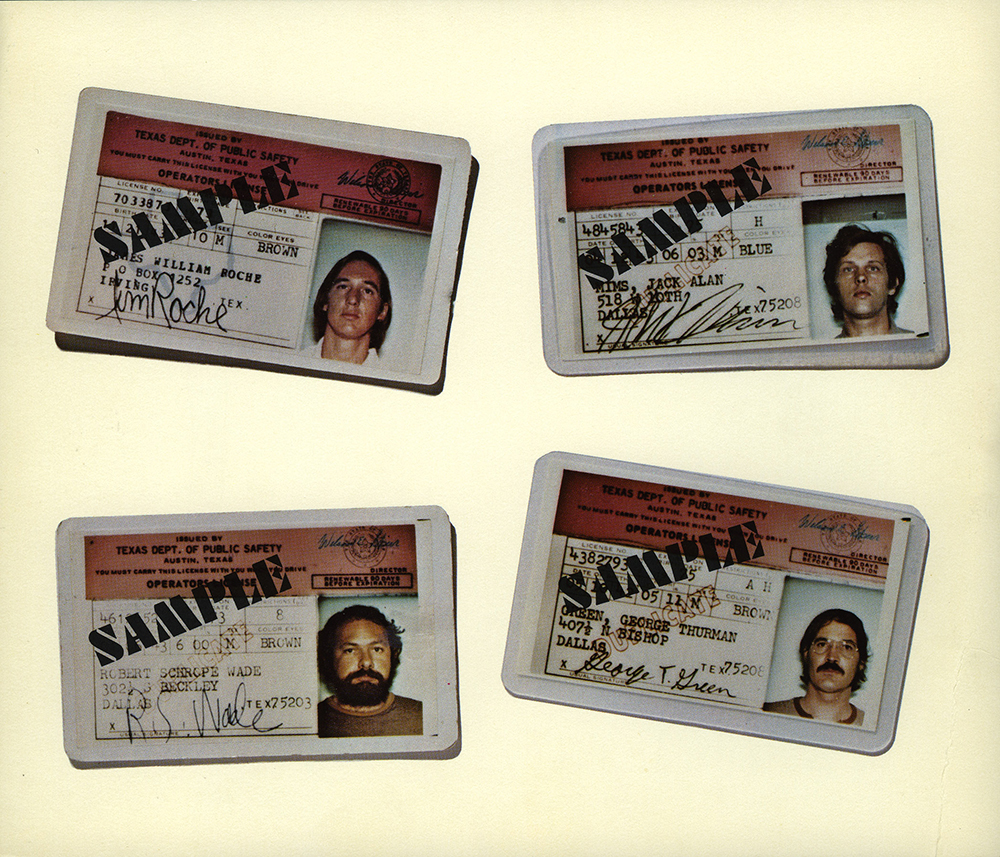

Artists George T. Green, Jack Mims, Jim Roche, Mac Whitney, and Robert (Daddy-O) Wade had all established studios in Oak Cliff by 1970 (Fig. 1). Living across the Trinity River from most of the art activity in Dallas, they took advantage of the freedom that comes with relative isolation. They were all about the same age, and nearly all were southerners by birth. Mims, Roche, and Green met as students in the MFA program at the University of Dallas. Though Mims was born and raised in Oak Cliff, Whitney was the first of the group to move there as a professional artist. Arriving in Texas in 1969 for his first solo exhibition at One Main Place (Fig. 13), Whitney established his studio in a two-story brick home next to a vacant lot near the Oak Farms Dairy (Fig. 29) and later moved to a ranch-style family home a few blocks from where Oswald shot Officer Tippit. Following Mims’ 1970 MFA thesis exhibition for UD, which was installed in the lobby of One Main Place (Fig. 2), he set up a studio in a home he inherited from his grandmother. With Mims’ encouragement, Roche followed, and then Wade moved into a converted loft space on the corner of Beckley Avenue and Jefferson Boulevard. Green moved into the area around Bishop Avenue and Eighth Street, now known as the Bishop Arts District, and combined several empty apartments into one huge space. Though Whitney lived near Green, Mims, Roche, and Wade and was part of their famous chili dinners at Wade’s studio, his loner mentality and strikingly different approach to his work separated him from the core group, who would become known as the Oak Cliff Four.

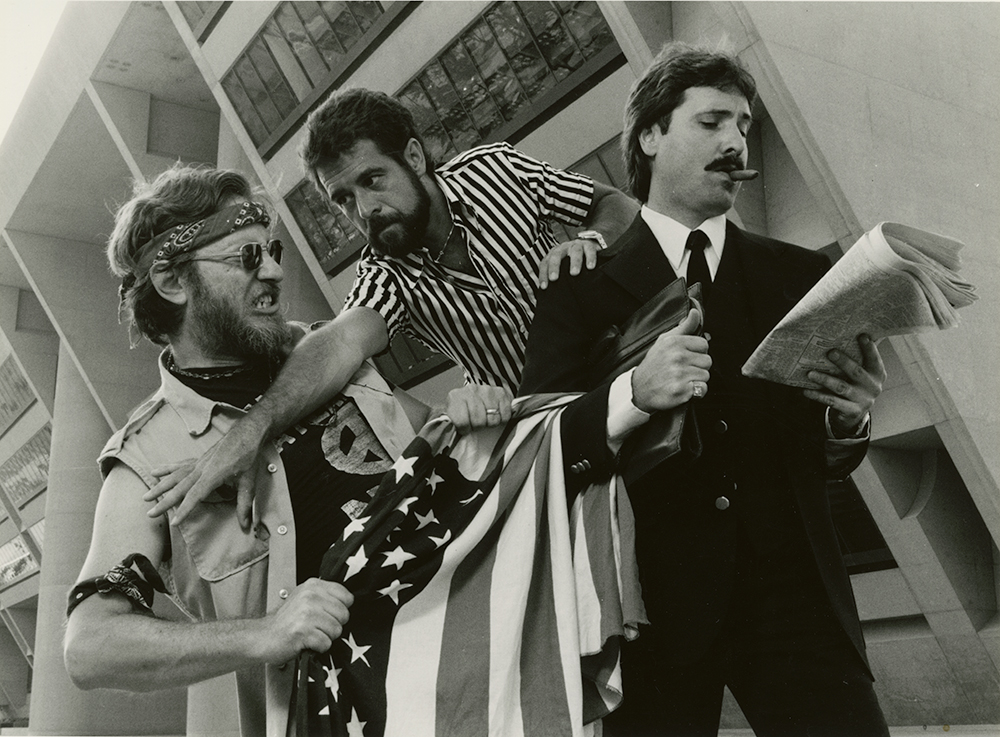

Artists working in Oak Cliff gained national attention when Newsweek featured them in a 1972 article titled “Big D.” It focused on Roche, Green, and Sam Gummelt just after an exhibition of their work at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts. A single, iconic image depicted four artists in Wade’s studio, with the caption, “Dallas artists Roche, Green, Mims, and Wade: Chili and bravado” (Fig. 30). Though the article never clearly defined a group, it may be the reason Roche, Green, Mims, and Wade were singled out as the Oak Cliff Four. A year later, the Oak Cliff Four had a group exhibition at the Tyler Museum of Art (Fig. 3, Fig. 31), solidifying their status as a four-man collective. Later in 1973 they had a group show at Dennis Hopper’s gallery in Taos, New Mexico.

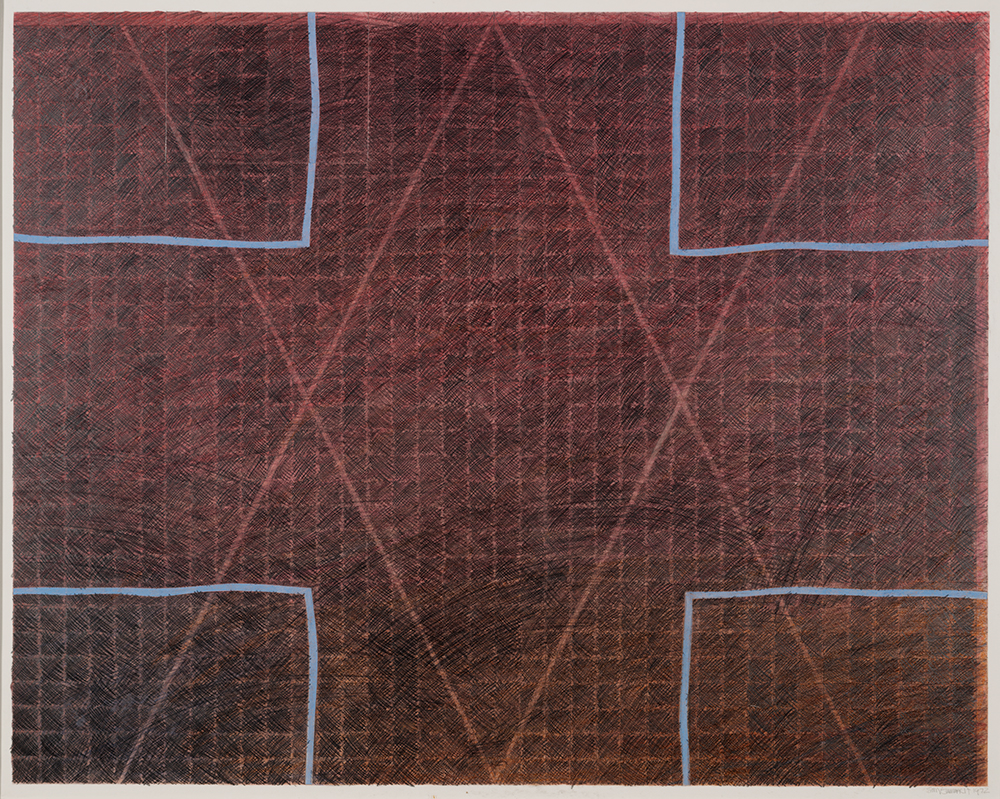

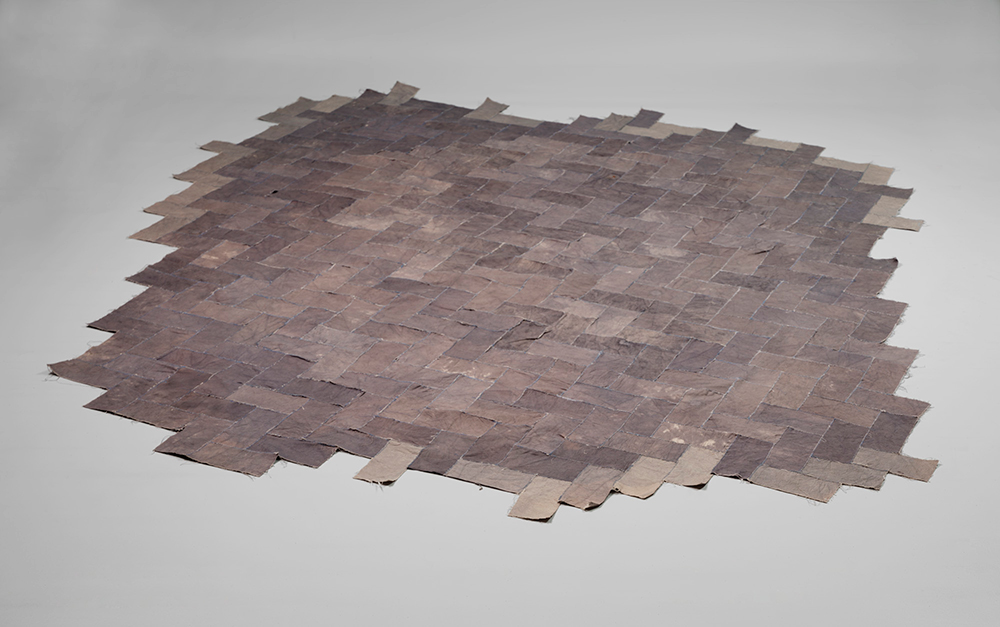

Looking at their work, it is not immediately apparent what Green, Mims, Roche, and Wade had in common. But they all drew on Texas mythologies for their subject matter in ways that became characterized as a certain style of Texas Funk. Hailing from Buddy Holly’s birthplace of Lubbock, Texas, Green was heavily influenced by 1950s nostalgia and referenced the kitschy culture of the time: Holly and rock-and-roll, drive-in movie theaters, cars, and 1950s household fixtures and decor. He constructed sculptures using out-of-date linoleum as his material (Fig. 9), as well as drawings in which cockroaches anthropomorphize as human characters with Texan costumes. Roche’s busty ceramic “mama plants” and ink-on-mylar drawings narrated the dysfunctional culture of Texas (Fig. 5, Fig. 6), while Mims’ more traditional practice of painting focused on symbolism with ominous overtones (Fig. 7). Wade’s work most directly reflected his surroundings, producing photo emulsion canvases that portrayed outlaws and social misfits like Bonnie and Clyde, Lee Harvey Oswald, and Jack Ruby (Fig. 8).

Though the Oak Cliff Four never thought of themselves as a collective, the group leveraged the popularity of their recently anointed brand and presented a united front as “part of a general movement . . . that was decentralizing the art world and breaking up the Minimalist hegemony.” The artists enjoyed wide-ranging local support, with galleries like Cranfill Gallery, Atelier Chapman Kelley, Janie C. Lee Gallery, and Delahunty Gallery giving them solo exhibitions. Henry T. Hopkins, director of the Fort Worth Art Center Museum (now the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth), and Fort Worth Star-Telegram arts critic Jan Butterfield furthered the group’s cause on a national level.

The four artists disbanded around 1974 when their individual careers took on greater importance. In 1973, Roche accepted a position at Florida State University in Tallahassee, and Mims followed a year later. Wade received a National Endowment for the Arts grant that year to realize a massive project: collecting objects, signs, memorabilia, and memories from across the country to install in his Bicentennial Map of the United States in North Dallas in 1976. This 300-foot-wide earthwork, which reflected Wade’s interaction with Robert Smithson at the Northwood Institute, included billboards touting, among other things, Tandy's Radio Shack and Big Boy Hamburgers, an Old Faithful water fountain from Wyoming, a telephone booth from Chicago, and 12 miniature skyscrapers courtesy of Continental Steel. The work caught the attention of People magazine, which featured Wade in its issue celebrating the U.S. Bicentennial.

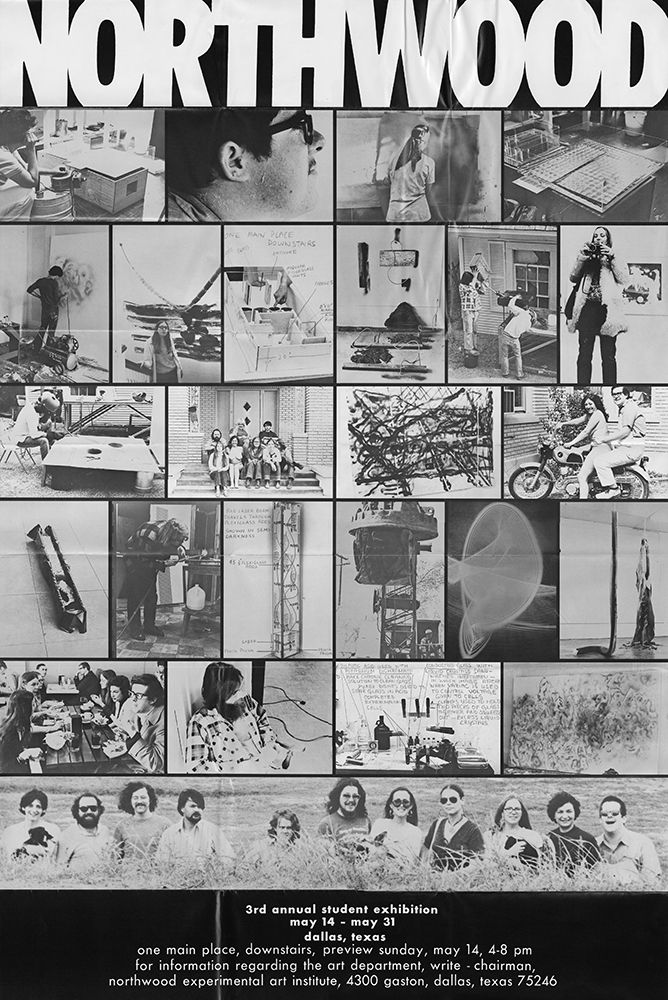

Northwood Institute’s Contemporary Arts Program

While living in his Oak Cliff studio, Bob Wade made trips back and forth to his teaching gig at a small, business-oriented, two-year college in far South Oak Cliff called Northwood Institute (Fig. 10). With a main campus in Midland, Michigan, by 1969 Northwood had branches in West Palm Beach, Florida; Cedar Hill, Texas; and Skowhegan, Maine. The specialized curriculum was “developed in cooperation with business and industry” and focused on “imparting new concepts of usable knowledge for use in today’s world through creative teaching and close association of the learning with the doing.” With the belief that its learning-by-doing strategy should also apply to the visual arts, Northwood introduced a contemporary arts program at the Dallas-area campus in 1968. While short lived, the program brought nationally recognized artists like Robert Smithson, Keith Sonnier, Italo Scanga, Alan Shields, and Billy Al Bengston to Texas. It also became an outlet for leading minds in the arts community, including Betty Blake, Evelyn Lambert, Chapman Kelley, and Henry Hopkins, to focus their energy on making great things happen in the underrecognized Dallas arts scene. The combination of art and technology put the program at the forefront of contemporary art practices, giving students hands-on experience working with engineers from Dallas-based Texas Instruments to create works of art using innovative technologies.

Since the merger of the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts with the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1963, many people involved with the DMCA and the local art scene had been looking for ways to promote contemporary art in Dallas. With the new Northwood Institute Experimental Contemporary Arts Program, they looked to the Cedar Hill campus as a center for this emerging interest (Fig. 11). The program offered a visual arts curriculum culminating in a two-year associate’s degree. Courses included art history, painting, life drawing, sculpture, and electives in filmmaking, photography, graphic design, and theater design. Teachers were practicing professional artists, and the campus regularly welcomed visiting artists.

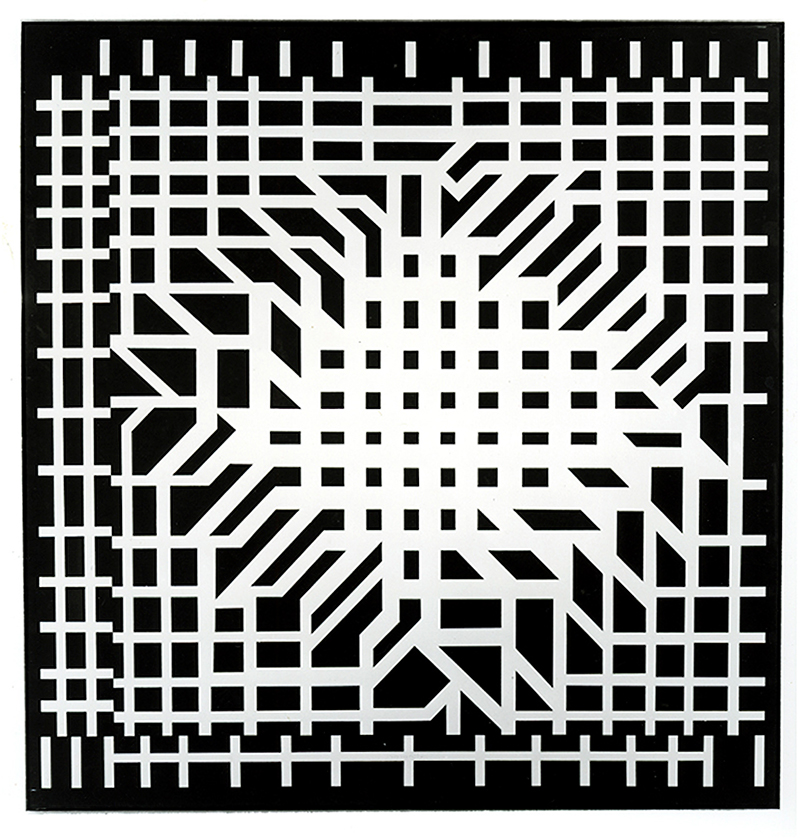

Local artist and gallery owner Chapman Kelley, who offered his services as an advisor, developed the initial idea for the program at Northwood, and in 1969 Kelley and his wife established the first scholarship fund for students. In its first year, the program enrolled 22 full-time students and three part-time students. Facilities on the Cedar Hill campus included a workshop, a display area, offices, a library room, a museum display area, and storage, along with studios for students and the director of education, Alberto Collie (Fig. 12). Students used materials like “laser beams, magnetic water, fiber optics, neon, polyurethane foam, polyurethane sheets, rock (natural), metal, environmental chambers, and stroboscopes.” Among the guest lecturers in the first year were Vassilakis Takis, Len Lye, Howard Wise, and Kenneth Snelson. Mr. and Mr. Joseph O. Lambert Jr. of Dallas gave the Northwood Institute one of Snelson’s large metal sculptures, which was installed outside the Lambert Commons building on campus and later temporarily installed in the lagoon at the DMFA in Fair Park (Fig. 14).

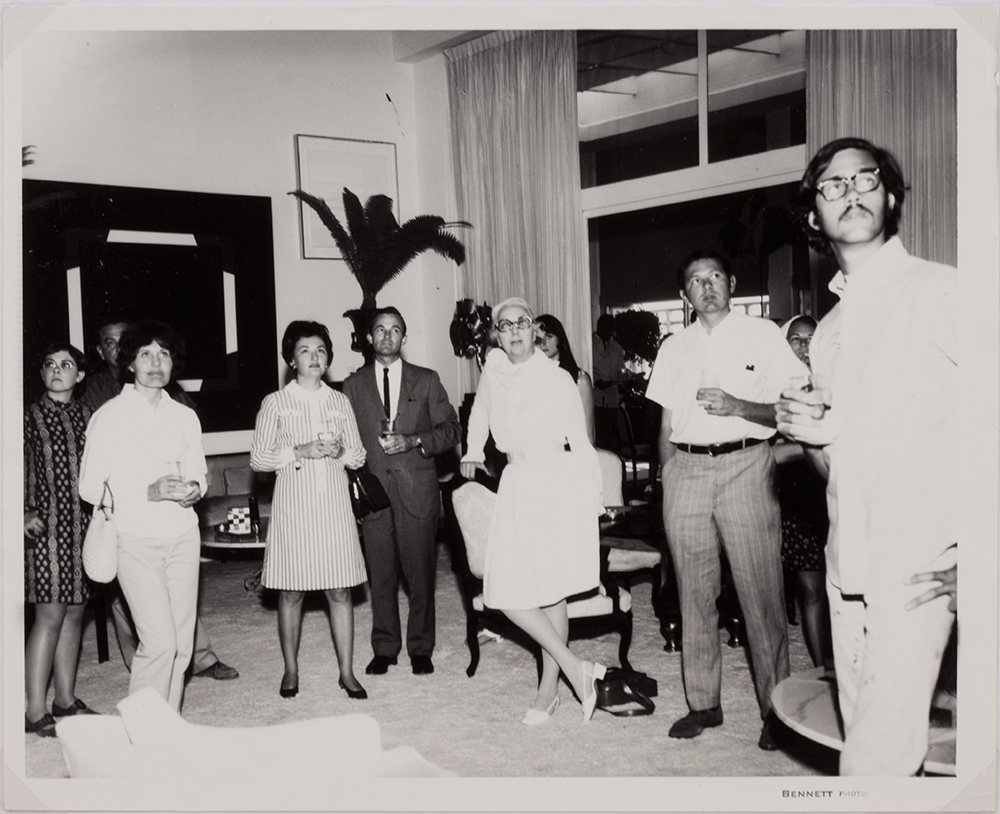

Despite the local success of the program, Northwood executives wanted national reach and visibility, so they appointed former DMCA director Douglas MacAgy as chairman of the contemporary arts advisory committee of the Northwood Institute of Texas. MacAgy—at the time a top official at the federal National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C.—called together personal friends and colleagues from the art world for the first advisory committee meeting in May 1970. They included some of the nation’s leading museum directors: Walter Hopps of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (later founding director of the Menil Collection, Houston); Leon Arkus of the Carnegie Institute Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Sebastian Adler of the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; and Henry Hopkins of the Fort Worth Art Center Museum. Among the other members were Victor D’Amico, director of education at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Robert Kaupelis, artist and professor of art at New York University; Carl Feiss, counselor on planning and urban design for the American Institute of Architects; and Rev. Roger Ortmayer, director of the department of church and culture, National Council of Churches of Christ, New York. Local committee members who attended were Alberto Collie, sculptor and director of the Northwood Contemporary Art and Experimental Art Institute; Paul Baker, director of the Dallas Theater Center; Betty Blake Guiberson, gallery owner; Chapman Kelley, artist and gallery owner; Lawrence Kelly, director of the Dallas Civic Opera; and Mrs. Clint Murchison Jr.

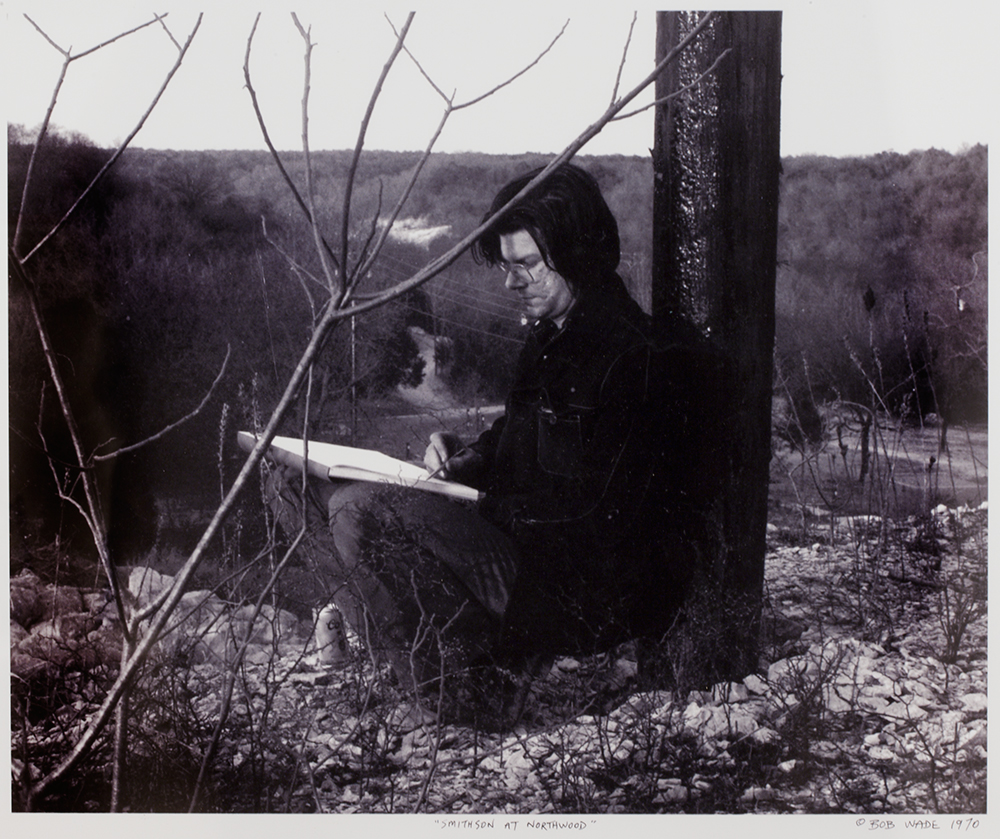

The committee changed the program’s name to the School of Contemporary Arts and discussed moving it to downtown Dallas, but decided that a campus location was more advantageous for students. Aspirations for the program were high, and it seemed to have a sound base of local and national support. Chapman Kelley contacted a group of well-known artists—including Philip Guston, Roy Lichtenstein, and James Rosenquist—about their interest in being visiting artists, and many of them were intrigued. But none of those on Kelley’s ambitious list ever made it to Northwood, and the little available material on the program suggests that the most famous artist to visit the campus was Robert Smithson, who arrived in late 1970.

During his weeklong visit, Smithson gave lectures to students and showed his recently completed film Spiral Jetty to students, faculty, and guests at the home of Betty Blake Guiberson. He also scouted out property on campus that appealed to him as a potential site for one of his signature “pour” works. Smithson did a series of nine drawings illustrating his ideas for the earthwork Texas Overflow, 1970 (Fig. 15, Fig. 16). The drawings also serve as a storyboard for a film documenting a sculpture/earthwork that was never completed. As former Northwood student and future gallery owner Eugene Binder recalls:

I remember he [Smithson] really didn’t have this outgoing personality, which is something I ended up seeing with Donald Judd. These people [artists] had . . . this vision and they had their work, and this was an important thing. And while they wanted to project it out into the world, they also . . . had their share of naysayers. There was a certain concentration that they had that was very interesting to me in their presence, and that was getting it done. I remember Smithson being kind of aggravated, I guess, because people didn’t jump up and say, “Yeah, I want to be a part of this!” . . . I know that there was a sort of disappointment, like, “okay, I made my pitch and it’s not happening here.”

Other artists who visited the Northwood Institute included painters Larry Zox, Christopher Wilmarth (Fig. 17), and Billy Al Bengston (who had exhibitions at the Janie C. Lee Gallery in Dallas during their visits), constructivist sculptor George Rickey, and light sculptor Keith Sonnier. Exhibitions of student work and major collections were installed in Lambert Commons, a new building dedicated to Mr. and Mrs. Joseph O. Lambert Jr., major Northwood benefactors who were instrumental in founding and developing the program. In March 1971, selections from the collection of Mrs. Harry Lynde Bradley of Milwaukee were on view, giving students, local artists, and residents the opportunity to see more than 50 major works of modern art. The Lambert Commons gallery stayed open seven days a week to allow ample time for visitors to see this important collection.

After the success of the Bradley exhibition, the contemporary arts program moved in 1972 to Downtown Dallas (Fig. 18, Fig. 19), where students would have easier access to the local art scene and be fully immersed in the culture of emerging artists just down the street in Deep Ellum. The new location at 4300 Gaston Avenue at Peak Street also came with a new director: Bob Wade. But after just four months in this location, Northwood Institute’s executive officers decided to move the program back to the Cedar Hill campus. Wade resigned soon after.

Funding problems continued to plague Northwood’s contemporary art program, and despite lofty aspirations and apparent support, it was doomed. Only a few months after the May 1970 advisory committee planning meeting, the president and vice president had expressed their concern over the program’s slow start. When MacAgy died in September 1973 and Hopkins left Fort Worth for San Francisco that same year, the program lost its greatest advocates. The advisory committee dissolved, and the contemporary arts program closed sometime the following year. Northwood Institute still had an interest in combining business with the arts. From 1974 through the 1980s, the Michigan campus offered seminars on arts management and circulated them among its satellite campuses.

Oak Cliff through the 1980s

Creative activity in Oak Cliff was relatively quiet by the 1980s. The Creative Arts Center of Dallas, established by a group of local arts patrons in 1965 in the studio home of early Oak Cliff artist Frank Reaugh, had been a vital presence during its 20 years in the neighborhood, but it moved to the Kramer Elementary School building in East Dallas in 1982. This community center offered classes in theater, sculpture, painting, drawing, and ceramics taught by area artists, along with exhibitions of work by instructors and visiting artists. Local sculptor Octavio Medellín, a former teacher at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts Museum School, established the Medellín School of Sculpture at the center in 1966.

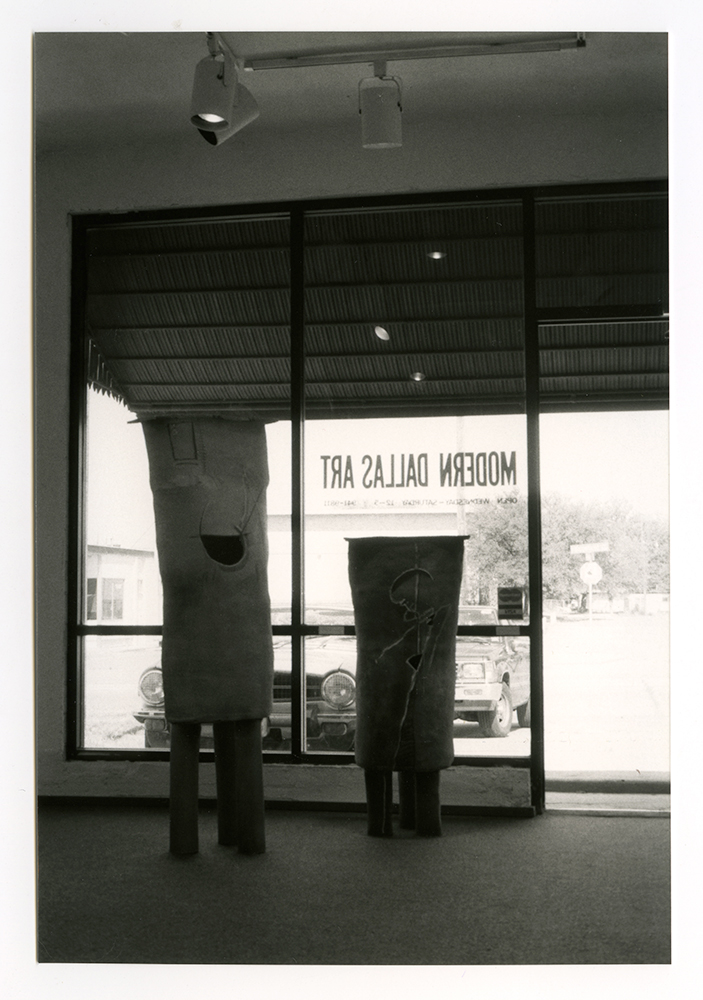

The few galleries remaining in the neighborhood tended to cater to diverse audiences. Arthello Beck Jr.—a member of the Southwest Black Artists Guild and a founder of the Association for Advancing Artists and Writers, Inc.—had established the Arthello Beck Gallery in 1974 in his home on Ramsey Avenue. His gallery featured the work of his friends and colleagues active in Dallas’ African-American arts community, such as photographer Carl Sidle and painters Nathan Jones, Jean Lacy, B. D. Norman, and Walter Winn. The gallery Modern Dallas Art had a successful run, attracting Dallasites across the river to Oak Cliff. Founded in 1986 by Glenn Lane and his partner Tim Thetford, its artists included Tony Holman, Rhea Burden, Gwen Norsworthy, Olya Cherentsova-Collins, Charlene Rathburn, Bob Nunn, Meg Loomis, Norman Kary, and George Moseley (Fig. 20, Fig. 21). It closed in 1990.

During the 1980s, local artists again began revitalizing parts of the neighborhood. Greg Metz, Bill Haveron, and Randy Twaddle moved into the vacant storefronts now known as the Bishop Arts District and jump-started the gentrification of the popular area. The concentration of notable Dallas artists living in Oak Cliff—including Tom Orr, Frank X. Tolbert 2, and Ann Lee Stautberg—inspired the creation of the bi-annual Oak Cliff studio tour (Fig. 22).

But artists also felt the negative impact of gentrification. In both Oak Cliff and Deep Ellum, the presence of artists in the community attracted nightclubs, and restaurants. Before long, developers sought a piece of the action. Eventually artists were priced out of neighborhoods they had helped to rejuvenate. By the mid- to late 1980s, developers had purchased many of the buildings Metz and his friends had renovated in the Bishop Arts District, sending them out to hunt for new space. Metz’s winning entry in the 1985 Oak Cliff Kinetic Sculpture parade was created in protest over the never-ending quest for space to live and work. The requirements for the judged competition were simple: original, “people-powered” works made of moving parts (Fig. 23, Fig. 24, Fig. 25). Metz’s Artist Wheel of Misfortune—an oversized hamster wheel powered by the artist running inside it—was adorned with a sign that read, “Oak Cliff used to raise artists and chickens. Now they only raise the rent (Fig. 26).”

South of the development in the Bishop Arts District, African-American artists were creating opportunities of their own. Ann Taylor Gallery, established in 1988 in the Westcliff Mall in South Oak Cliff, was the first of the new galleries to feature their work. In 1989, three more galleries opened: Ebony Fine Arts Gallery, Roots Gallery (in Deep Ellum), and Visions in Black. These spaces catered to the predominantly African-American residents of Oak Cliff, offering them the opportunity to see and be inspired by the work of African-American artists.

Into the 21st Century

Oak Cliff welcomed its first official cultural center in 1997 with the opening of the Ice House Cultural Center in a 1908 building at 1004 West Page Street. Part of the City of Dallas Office of Cultural Affairs, it was a Latino-focused venue to promote arts and cultural events that reflect the diversity of Oak Cliff and surrounding neighborhoods. The center closed in 2009 and reemerged in 2010 as the Oak Cliff Cultural Center in a new location next door to the historic Texas Theatre. It has an art gallery and multipurpose studio and offers workshops, musical performances, dance classes, and summer camps for all ages. The gallery is open to exhibition submissions and has hosted exhibitions such as La Genta de la Revolución (November 2010–January 2011), historic photographs that document the Mexican Revolution; XXI: Conflicts in a New Century (April 2011), a group photography exhibit curated by locals Charles Dee Mitchell and Cynthia Mulcahy; and Oak Cliff in Transit (July–August, 2012), a “visual homage” to the neighborhood through paintings and conceptual works by Mathew Barnes, Rosie Lee, and Orlando Sanchez.

The neighborhood welcomed its first artist residency in 1998 with Art Landing, established by Rachel Stirewalt and her husband J. D. Varnell as a combination gallery, workspace, and residence. The couple renovated the old warehouse, which accommodates up to 12 artists in its vast 11,000-square-foot space. In 2005, La Reunion TX (LRTX) was established on 35 acres in West Oak Cliff. In this nontraditional residency, artists are invited to create site-specific ephemeral works in tune with the natural environment, based on the premise that “art and artists are critical to a thriving community . . . [and] need a chance, from time to time, to recharge their creative spirit.” Regular programs include Art Chicas, which teams high school students with established artists; Found Object Art, a partnership with the Nasher Sculpture Center and the Dallas Independent School District; and Environmental Art, an annual juried program in which local artists to create works using materials from the LRTX grounds.